Okay, let's dim the lights and settle in. Some films hit you like a blockbuster explosion, all sound and fury signifying... well, often quite a lot of fun, actually. But then there are others, films that seep into your consciousness slowly, like smoke under a door, leaving an impression that lingers long after the VCR whirs to a stop. Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1978) belongs firmly in the latter category. It’s a film many of us likely missed during its initial, near-invisible release, overshadowed by louder, slicker fare. Yet, encountering it later, perhaps through a revival screening or a hard-won restored copy, feels like uncovering a hidden masterpiece – a raw, poetic statement whispering truths from the heart of 1970s Watts, Los Angeles.

### More Than a Movie, A Captured Moment

This wasn't churned out by a studio; Killer of Sheep was Burnett's thesis project for UCLA film school, famously shot on weekends over more than a year with a minuscule budget (reportedly under $10,000) using borrowed equipment and largely non-professional actors drawn from the community it depicts. That context isn't just trivia; it's baked into the film's very soul. There's an intimacy, an unvarnished authenticity here that feels less like fiction and more like captured life. It eschews a conventional plot, opting instead for a series of vignettes orbiting Stan (Henry G. Sanders), a sensitive, weary man working long hours at a slaughterhouse, struggling to maintain his dignity and connection to his family amidst the grinding realities of poverty.

### The Weight of the World on Weary Shoulders

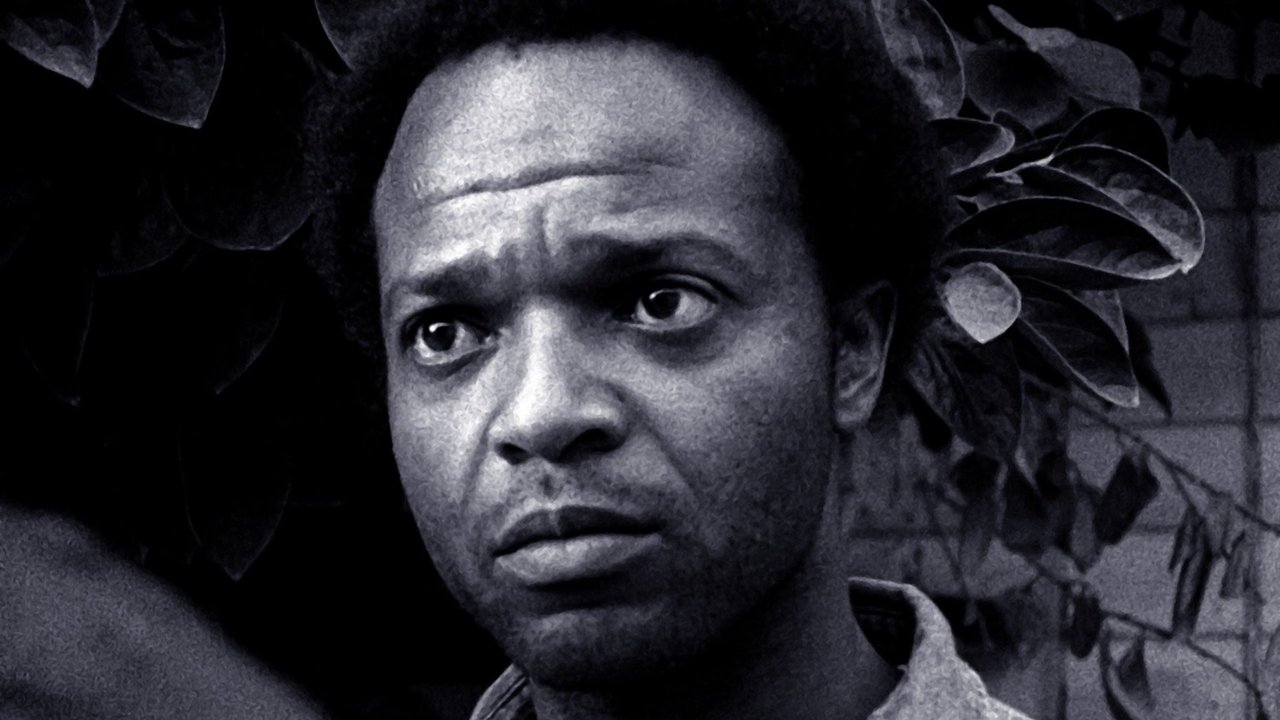

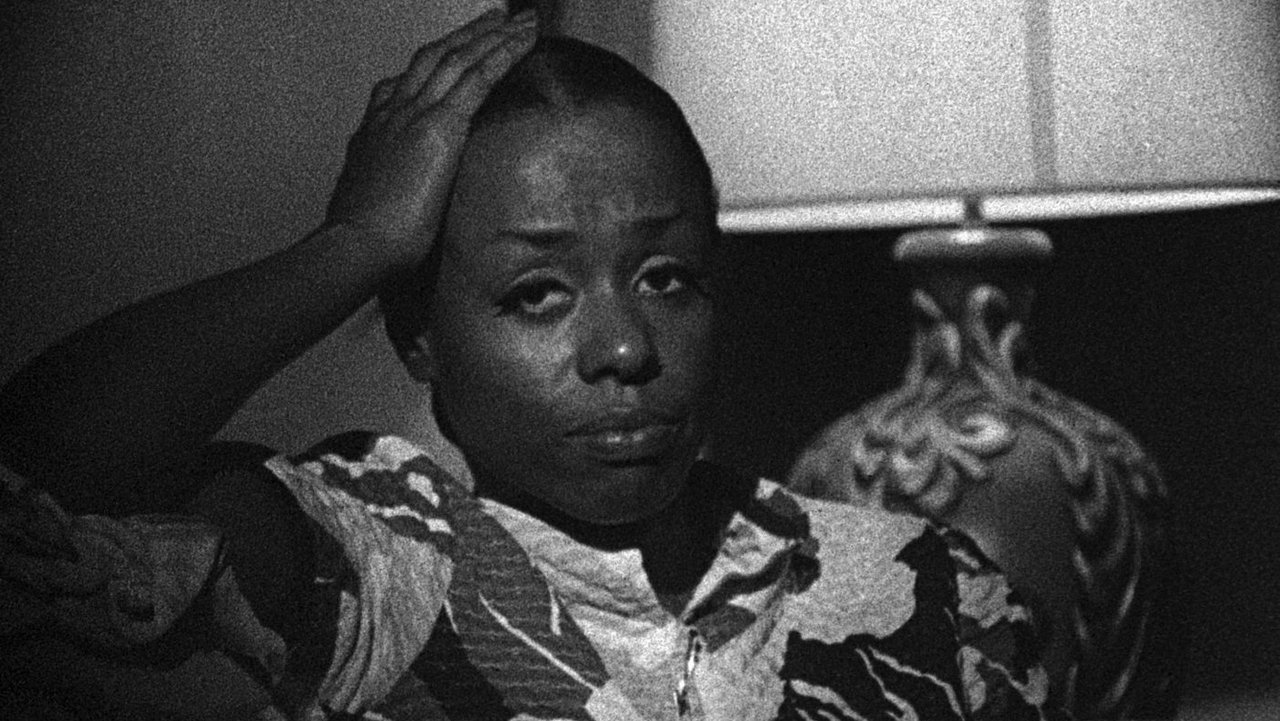

Henry G. Sanders delivers a performance of profound, quiet power. Stan isn't a man of grand speeches; his exhaustion, his internal struggles, his flickers of tenderness and frustration are conveyed through his posture, the set of his jaw, the deep fatigue in his eyes. We see him at work, grappling with the brutal, repetitive task referenced in the title – a metaphor, perhaps, for the dehumanizing effect of his labor and the cyclical nature of the life he feels trapped in. We see him at home, trying to connect with his wife (Kaycee Moore, equally affecting in her resilience and quiet disappointment) and children, but often finding himself emotionally distant, weighed down by pressures he can barely articulate. What does it do to a man's spirit, the film seems to ask, to spend his days ending lives just to sustain his own?

### Life Between the Cracks

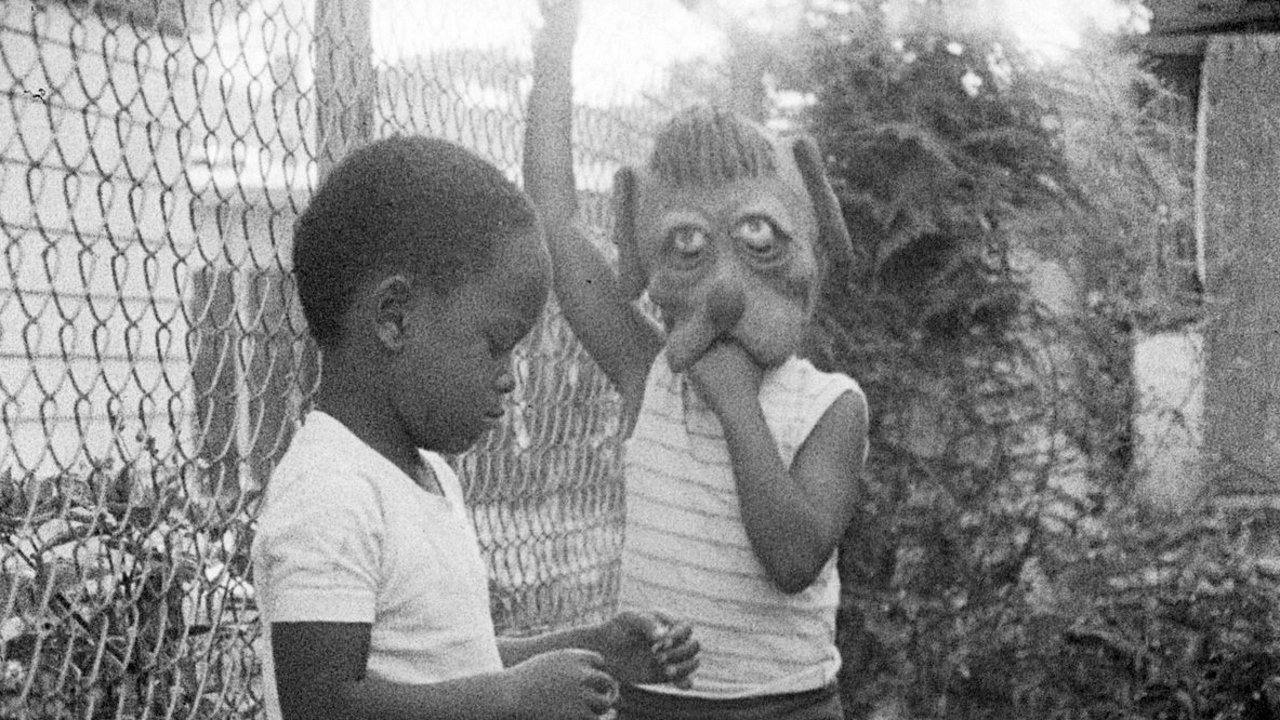

Burnett’s direction is lyrical and observational. He finds poetry in the mundane: children leaping across rooftops against a smoggy sky, a slow dance between Stan and his wife that’s both tender and achingly sad, moments of communal laughter and shared hardship. The camera often lingers, allowing scenes to unfold with a natural rhythm, capturing the textures of the environment – the cramped houses, the dusty lots, the constant presence of children finding ways to play and exist amidst the urban decay. This isn't poverty tourism; it's a deeply empathetic portrayal of a specific time and place, rendered with aching beauty and realism. The episodic structure might frustrate viewers seeking clear narrative arcs, but it perfectly mirrors the feeling of lives lived day-to-day, where meaning is found not in grand events, but in small, accumulated moments.

### A Lost Classic Found

For decades, Killer of Sheep remained tragically difficult to see, primarily due to the prohibitive cost of clearing the rights for its evocative soundtrack, which featured artists like Dinah Washington, Paul Robeson, and Earth, Wind & Fire. This wasn't just background music; it was integral to the film's mood and cultural specificity. Its eventual restoration and re-release in 2007 felt like a major cinematic event, finally allowing wider audiences to appreciate a work the National Society of Film Critics had already hailed as one of the 100 essential films ever made. It stands in stark contrast to the Blaxploitation films popular in the same era, offering a grounded, humanistic perspective far removed from genre tropes. It feels less like a product of its time and more like a timeless document about its time.

Does its non-linear, almost documentary style make it less engaging than a tightly plotted thriller? Perhaps for some. But its power lies elsewhere – in its unflinching honesty, its deep empathy, and its ability to find grace and humanity where many wouldn't bother to look. It forces a confrontation with uncomfortable realities but does so with artistry and profound compassion.

Rating: 9.5/10

Justification: Killer of Sheep is a landmark of American independent cinema and a cornerstone of Black filmmaking. Its technical limitations become strengths, fostering an unparalleled naturalism. The performances, particularly Sanders', are deeply felt and authentic. While its episodic nature and challenging subject matter might not offer conventional entertainment, its artistic merit, emotional resonance, historical significance, and poetic realism are undeniable. The slight deduction acknowledges that its pacing and structure might not resonate universally, but its power is immense.

Final Thought: This is more than just a film; it's a vital piece of American social realism, a quiet cry from the heart that, once heard, is impossible to forget. It reminds us that beneath the noise of blockbusters, cinema can also be a window into the soul, reflecting the profound struggles and quiet dignity of everyday life.