The air hangs thick and salt-heavy, even through the static haze of the television screen. Some films don't need jump scares or elaborate monsters to burrow under your skin. They just need isolation, simmering resentment, and the unsettling feeling that the world itself is turning against you. Such is the quiet, creeping power of Colin Eggleston's 1979 Australian gem, Long Weekend. This isn't your typical creature feature; it's something far more insidious, a slow burn that leaves a residue of profound unease.

Paradise Lost, Or Just Trashed?

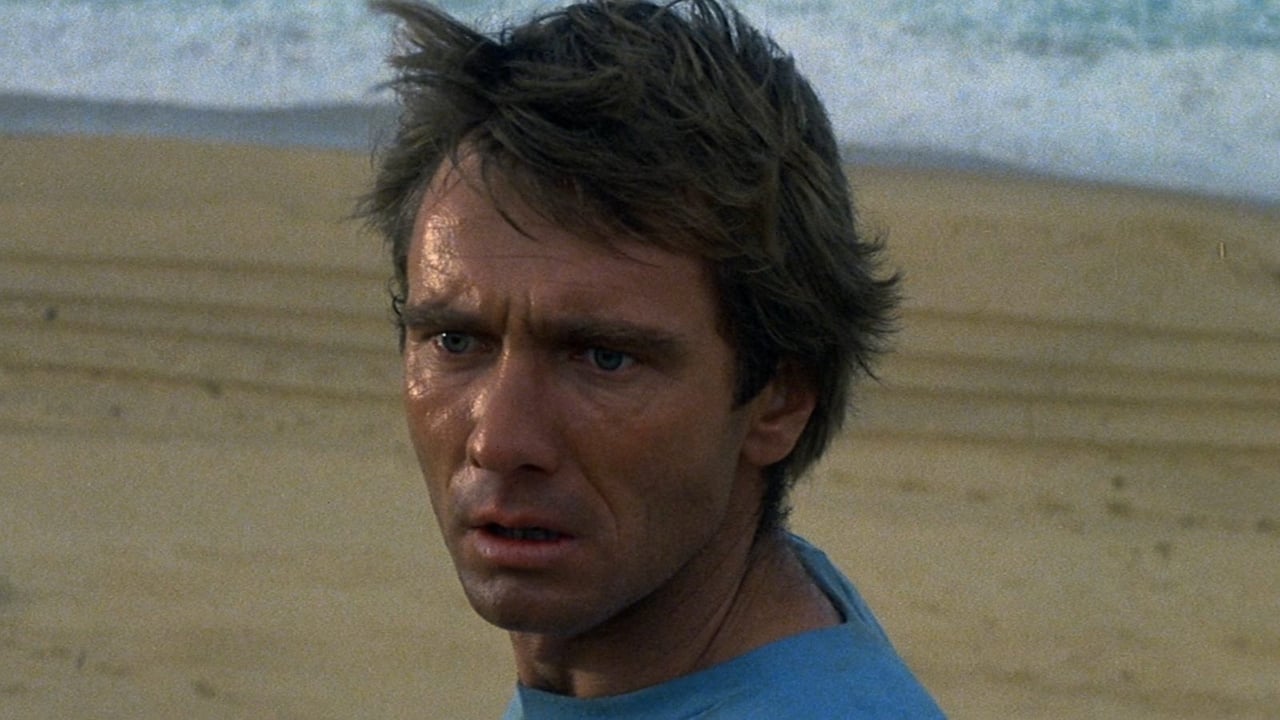

We meet Peter (John Hargreaves) and Marcia (Briony Behets), a couple whose marriage is clearly as eroded as the coastal tracks they recklessly drive their car down. Seeking a weekend escape to a remote beach, their idea of communing with nature involves chucking cigarette butts into the brush, accidentally running over a kangaroo, smashing an eagle's egg, and generally treating the pristine wilderness like their personal garbage dump. Their contempt for each other is palpable, spilling over into a casual disregard for the environment around them. It's this carelessness, this ambient toxicity, that sets the stage for nature's subtle, chilling reprisal. Hargreaves and Behets, who were reportedly a couple off-screen during filming, bring a biting authenticity to the couple's frayed dynamic, making their interactions almost uncomfortably real.

The Sound of Silence, Amplified

What makes Long Weekend so effective, especially viewed through the lens of memory on a flickering CRT, is its masterful use of atmosphere. Eggleston, working from a sharp script by the legendary Australian screenwriter Everett De Roche (who also penned genre favourites like Patrick and Roadgames), understands that true horror often lies in suggestion. Inspired by a miserable camping trip of his own, De Roche crafted a narrative where the threat isn't a singular entity but the cumulative weight of small, unsettling events. The constant cries of unseen birds, the eerie stillness of the water, the rustling in the undergrowth – the sound design is phenomenal, turning the natural world into an oppressive, watchful presence. Forget a booming score; the unnerving symphony here is purely environmental, amplified to chilling effect. Shot on a shoestring budget (reportedly around $480,000 AUD), the film wisely leans into this psychological dread rather than costly spectacle.

Nature's Passive Aggression

The 'horror' elements unfold with excruciating patience. There are no masked killers or rampaging beasts in the conventional sense. Instead, animals behave strangely. Objects disappear or move. The tides seem malevolent. Is it supernatural intervention, or merely the psychological manifestation of the couple's guilt and paranoia projected onto their surroundings? De Roche intended it as nature actively striking back, but the film leaves just enough ambiguity to let your own interpretations fester. Remember that shape gliding beneath the waves? The script called for a dugong, a normally placid creature, to appear menacingly, but finding and filming one proved difficult, adding to the film's list of subtle, almost subliminal threats. The location itself, shot primarily in the Mimosa Rocks National Park in New South Wales, becomes a character – beautiful, isolated, and increasingly hostile. The sheer remoteness achieved on that modest budget feels incredibly authentic, contributing significantly to the suffocating tension.

A Warning Whispered on the Wind

Beyond the marital strife and creeping dread, Long Weekend carries a potent environmental message that feels startlingly prescient today. Released long before climate change became a daily headline, the film tapped into a growing unease about humanity's impact on the planet. Peter and Marcia aren't evil masterminds; they're just thoughtless, self-absorbed individuals whose casual disregard triggers devastating consequences. It’s a form of horror rooted not in ancient curses or alien invaders, but in our own mundane carelessness. This thematic depth elevates Long Weekend beyond simple "Ozploitation" thrills, making it a film that resonates intellectually as well as viscerally. Its initial reception was somewhat muted, perhaps because its slow-burn, ambiguous nature didn't fit neatly into horror conventions of the time, but it has rightfully earned its status as a cult classic Down Under and beyond.

The Verdict

Long Weekend isn't about shocks; it's about a permeating dread, the kind that lingers like campfire smoke on your clothes. It excels in building an almost unbearable atmosphere of isolation and psychological decay, using the natural landscape and sound design to maximum effect. The central performances are raw and believable, grounding the increasingly strange events in relatable human conflict. While its deliberate pacing might test some viewers accustomed to faster-paced horror, its commitment to mood and its chilling environmental subtext make it a standout. It’s a testament to how effective minimalist horror can be when crafted with intelligence and patience. Does that final, desperate cry echoing across the empty beach still send a shiver down your spine?

Rating: 8/10

A masterclass in atmospheric tension and subtle environmental horror. Long Weekend proves that sometimes the most terrifying monsters are the ones we create through our own neglect, both of the world around us and the relationships within it. It’s a quiet nightmare that gets under your skin and stays there.