The hum begins subtly, almost lost beneath the arid Texas air. But it grows. A low, insistent vibration that promises not thunder, but something far more insidious. Irwin Allen, the undisputed Master of Disaster following blockbusters like The Poseidon Adventure and The Towering Inferno, turned his sights from capsized liners and burning skyscrapers to something smaller, yet exponentially more numerous: millions upon millions of pissed-off Africanized killer bees. And in 1978's The Swarm, he threw everything, including an absolutely staggering $21 million budget (around $98 million today!), at making us afraid. Very afraid.

The Hubris of the Hive

You have to admire the sheer audacity. Allen assembled a cast that reads like a Golden Age Hollywood reunion crossed with 70s stalwarts: Michael Caine, Katharine Ross, Richard Widmark, Richard Chamberlain, Olivia de Havilland, Ben Johnson, Lee Grant, José Ferrer, Patty Duke, Slim Pickens, and even the legendary Henry Fonda. All brought together by an Oscar-winning writer, Stirling Silliphant (In the Heat of the Night), to battle... bees. It's the kind of high-concept pitch that sounds both terrifyingly primal and faintly ridiculous, a line the film itself straddles with often clumsy, occasionally fascinating, results. Michael Caine famously quipped he'd never seen the film but had seen the house it paid for, a sentiment likely shared by others lured by Allen's Midas touch.

Nature's Tiny Terrors

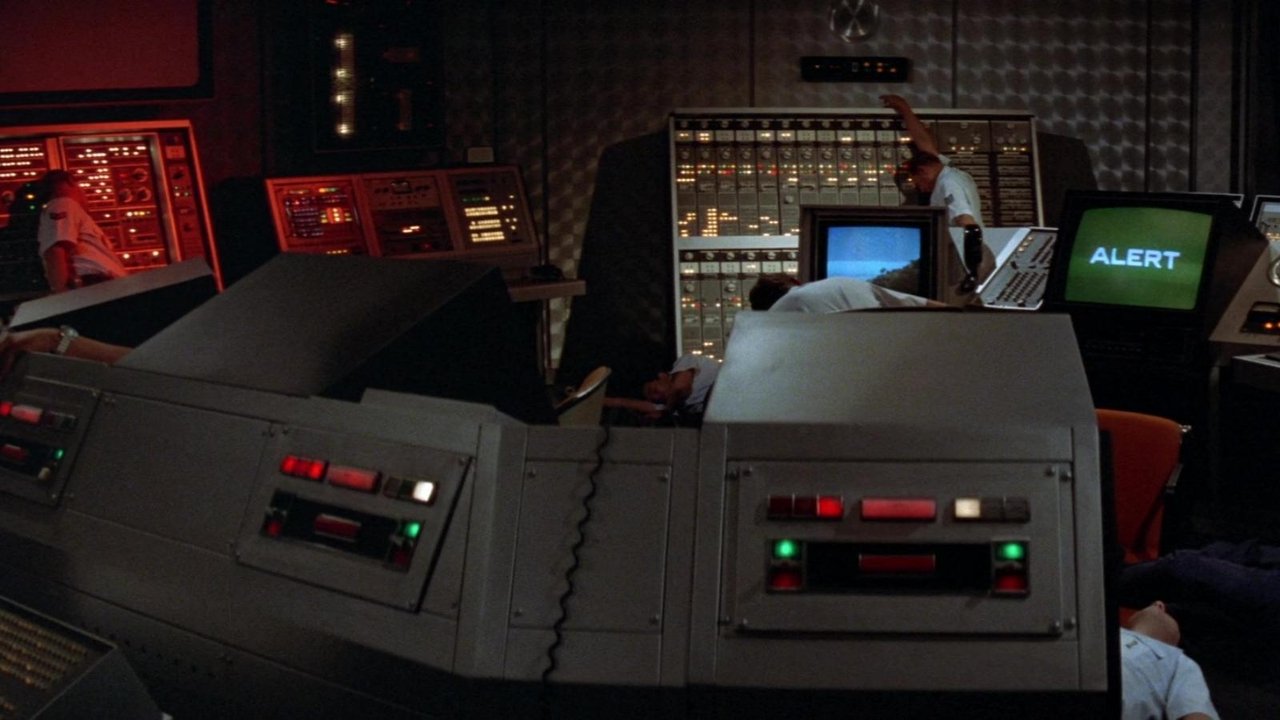

The plot, true to disaster form, is sprawling. Michael Caine stars as Dr. Bradford Crane, the requisite brilliant-but-ignored entomologist who understands the apocalyptic threat posed by a mutated, hyper-aggressive strain of South American bees invading the US. Richard Widmark embodies military skepticism as General Slater, initially favouring brute force (flamethrowers!) over science. Katharine Ross is Captain Helena Anderson, the base doctor caught between science and protocol. From a deadly attack on an Air Force base, the buzzing menace spreads, engulfing small towns, derailing trains (a sequence involving miniatures that likely looked far more convincing on a fuzzy CRT screen), and threatening Houston itself. Allen pulls out all the stops, depicting mass panic, heroic sacrifices, and governmental incompetence on an epic scale. The intended dread is palpable – the idea of an unstoppable, indifferent force of nature overwhelming humanity remains potent. Doesn't that image of the town square, silent save for the drone, still carry a certain chilling weight?

Struggles Behind the Swarm

Bringing this vision to life was reportedly fraught with challenges, especially concerning the film's titular stars. Working with potentially millions of bees required extreme measures; rumour has it that countless bees had their stingers painstakingly removed by hand to protect the actors during close-ups. To ensure they looked suitably 'killer', some bees allegedly even had their abdomens painted a more vibrant yellow. It speaks volumes about Allen’s commitment to practical spectacle, even when dealing with antagonists barely visible on screen. The film's production difficulties perhaps mirror the on-screen chaos; Allen, known for his hands-on approach, apparently clashed with Silliphant over the script, contributing to the often clunky dialogue that even this stellar cast struggles to elevate.

Atmosphere vs. Absurdity

Does the film succeed in creating genuine terror? Often, no. The sheer earnestness clashes with moments of pure, unintentional camp. Scenes like the bee attack during a town picnic, or the hallucination sequences suffered by victims, veer into the bizarre. The runtime, especially in longer cuts sometimes found on VHS or later releases, can feel punishingly slow between the set pieces. Yet, there's an undeniable quality to its very excess. Jerry Goldsmith, a composer capable of true genius (think Alien, Chinatown), provides a score that tries valiantly to inject menace and grandeur, sometimes succeeding in capturing the scale of the threat, other times feeling slightly overwrought for scenes involving actors flailing at buzzing overlays. The practical effects, from the matte paintings of bee-covered cities to the (infamous) exploding helicopter, have that distinct, tangible quality so characteristic of the era – charmingly dated now, perhaps, but possessing a weight CGI often lacks. I distinctly remember renting the hefty double-VHS box set back in the day, the sheer size promising an event.

A Cult Legacy Built on Failure

Commercially, The Swarm was a notorious bomb, signalling the beginning of the end for the 70s disaster movie cycle and significantly damaging Irwin Allen's producing career. Critics were savage. Its reputation lingered for years as a punchline, a prime example of Hollywood excess gone wrong. Yet, time and the warm glow of nostalgia have been strangely kind. It’s achieved a certain cult status among fans of cinematic oddities and disaster epics. It’s a film you watch because of its flaws as much as despite them. The sincerity of its attempt, the sheer star power committed to the ludicrous premise, and the glimpses of genuine B-movie panic make it strangely compelling. It’s a fascinating artefact of a specific moment in blockbuster filmmaking, before irony fully took hold.

***

VHS Heaven Rating: 4/10

Justification: The Swarm earns points for its incredible ambition, jaw-dropping cast, and moments of pure, unintentional retro camp that provide entertainment value Allen likely never intended. The practical effects have a certain charm, and the core concept could have been terrifying. However, it loses significant points for its punishing length, often dreadful dialogue, scientific absurdities, inconsistent tone, and ultimate failure to deliver genuine scares or compelling drama despite its budget and talent. It's more fascinating failure than misunderstood masterpiece.

Final Thought: While it may have crash-landed at the box office, The Swarm buzzes on in the realm of cult cinema – a spectacular, star-studded misfire that’s arguably more fun to talk about (and occasionally chuckle at) than it is to genuinely fear. It’s a monument to a bygone era of disaster filmmaking, preserved forever on those chunky VHS tapes.