It starts, as these things often do, with a whisper turning into legend. The baby alligator, a vacation souvenir flushed away in a moment of parental pique, vanishing into the labyrinthine darkness beneath the city streets. We all heard variations of that story growing up, didn't we? But John Sayles (the sharp mind behind Piranha and later Lone Star) took that urban myth and let it fester, grow, and eventually, emerge in 1980's Alligator. This isn't just another creature feature; it carries a certain grimy authenticity, a weariness that clings long after the tape stops rolling.

Down in the Guts of the City

Directed by Lewis Teague, who would later bring Stephen King's rabid Cujo to the screen, Alligator masterfully blends the tropes of a monster movie with the weary cynicism of a 70s cop drama. Forget pristine beaches and open water; the terror here breeds in the filth and shadow of Chicago's (though largely filmed in Los Angeles) sewer system. The atmosphere is thick with urban decay, a sense that something monstrous thriving in our own discarded waste feels disturbingly plausible. Teague uses the claustrophobic tunnels and grimy alleys to build a palpable sense of dread before the titular beast even makes its grand, terrifying entrance. The city itself feels like a character – indifferent, decaying, and hiding secrets best left undisturbed.

A Hero Grounded in Grit

At the heart of the mounting chaos is Detective David Madison, played with understated brilliance by the late, great Robert Forster. Forster, decades before his Oscar-nominated resurgence in Jackie Brown, gives Madison a quiet dignity and a palpable sense of exhaustion. He’s not a gung-ho action hero; he's a cop haunted by a past tragedy, balding, world-weary, and initially disbelieved by his superiors. It’s this grounding that makes the escalating absurdity work. When Madison insists something ancient and enormous is lurking below, Forster sells the conviction born of weary experience, not B-movie hysterics. His interactions with Robin Riker as the initially skeptical herpetologist Marisa Kendall provide the film's human core, a believable connection forged amidst the escalating reptilian horror.

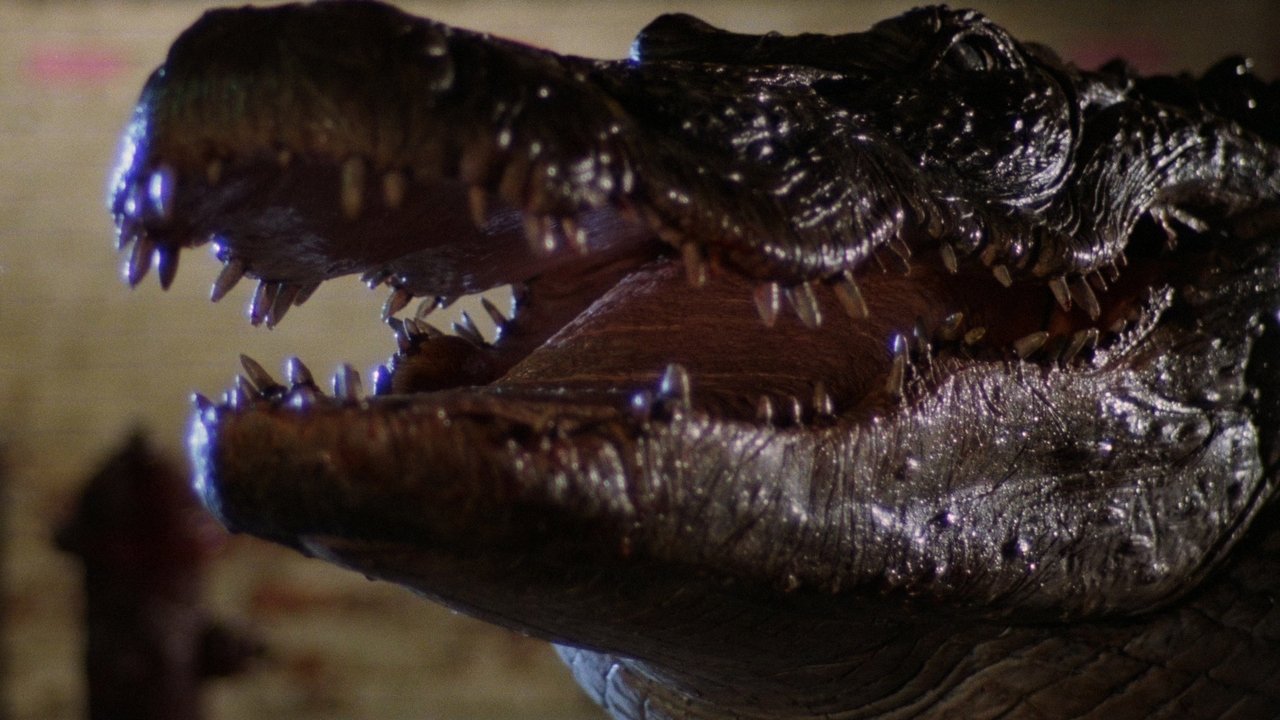

Ramon Rising: Practical Effects Nightmare Fuel

Let's talk about Ramon, the colossal consequence of illicit growth hormones dumped by a greedy pharmaceutical company – Sayles’s script subtly weaving in that era's anxieties about corporate malfeasance. While modern CGI might render a smoother creature, there’s an undeniable physical presence to the effects here that digital creations often lack. A combination of live caimans for the smaller scenes and, crucially, a massive, 30-foot animatronic beast for the money shots, Ramon feels real in a way that chills. You sense the weight, the leathery texture, the sheer primal force. Reportedly, the large mechanical alligator was cumbersome and difficult to operate, especially during water sequences, but these technical hurdles perhaps inadvertently added to the creature’s lumbering, unstoppable menace on screen. Seeing that thing burst through concrete or surface in a swimming pool… well, those images burrowed deep into the minds of many a young VHS viewer. Remember that pool party scene? It remains a masterclass in sudden, shocking carnage.

More Than Just Chomping

What elevates Alligator beyond its B-movie brethren is undoubtedly John Sayles's script. Reportedly penned quickly to rework an existing concept, it’s packed with sharp dialogue, surprisingly well-developed characters (even minor ones get moments to shine), and a vein of dark, cynical humor. There’s intelligence at play here, a refusal to simply tick boxes. We get glimpses into the lives disrupted by Ramon – the corrupt corporate suits, the grizzled sewer workers, the oblivious socialites – adding texture and stakes. The film even finds time for eccentric supporting characters like Michael V. Gazzo as Chief Clark, chewing scenery and bureaucratic red tape with equal gusto. Sayles understood that the best monster movies are as much about the people reacting to the monster as the beast itself.

A Cult Classic With Bite

Produced on a relatively modest budget of around $1.75 million, Alligator became a solid sleeper hit, pulling in over $6.5 million – a tidy profit translating to roughly $24 million today, proving audiences were hungry for well-crafted creature carnage. It arrived in the wake of Jaws, certainly, but carved its own niche with its urban setting and gritty tone. It wasn't just about the scares; it was about the rot beneath the surface, both literal and metaphorical. Renting this tape often meant expecting straightforward schlock, but discovering something smarter, meaner, and surprisingly resonant. Its influence can be seen in later urban monster flicks, but few capture its specific blend of weariness and visceral thrill. Doesn't that practical, hulking gator design still feel unnervingly effective?

VHS Heaven Rating: 8/10

Alligator earns its high marks for delivering exceptional creature feature thrills anchored by a fantastic lead performance from Robert Forster and elevated by John Sayles’s sharp, intelligent script. The practical effects, while dated by today’s standards, possess a tangible menace, and Lewis Teague directs with a keen eye for atmospheric dread and impactful scares. It stumbles occasionally, perhaps leaning into some genre clichés, but its overall quality, dark humor, and surprisingly thoughtful core make it stand out.

It’s more than just a movie about a giant alligator; it’s a snapshot of urban anxieties, a gritty character study wrapped in monster mayhem, and a prime example of how smart writing and committed performances can elevate genre filmmaking. A true gem from the depths of the VHS era that still has plenty of bite.