The year 2000 felt like crossing a threshold, didn't it? The anxieties of Y2K faded, the future seemed wide open, yet some cinematic echoes of the recent past still lingered. Watching James Ivory's adaptation of Henry James' The Golden Bowl, released right on that cusp, feels very much like witnessing the elegant, perhaps final, flourish of a certain kind of filmmaking that truly blossomed in the 80s and early 90s. It arrived a little late for the peak VHS era, predominantly a DVD release, I recall, but its soul feels intrinsically linked to those earlier, sumptuous Merchant Ivory productions many of us discovered on worn-out tapes rented from the 'Classics' or 'Drama' section. It carries that same deliberate pacing, that meticulous attention to unspoken feeling we remember so well.

An Exquisite, Suffocating World

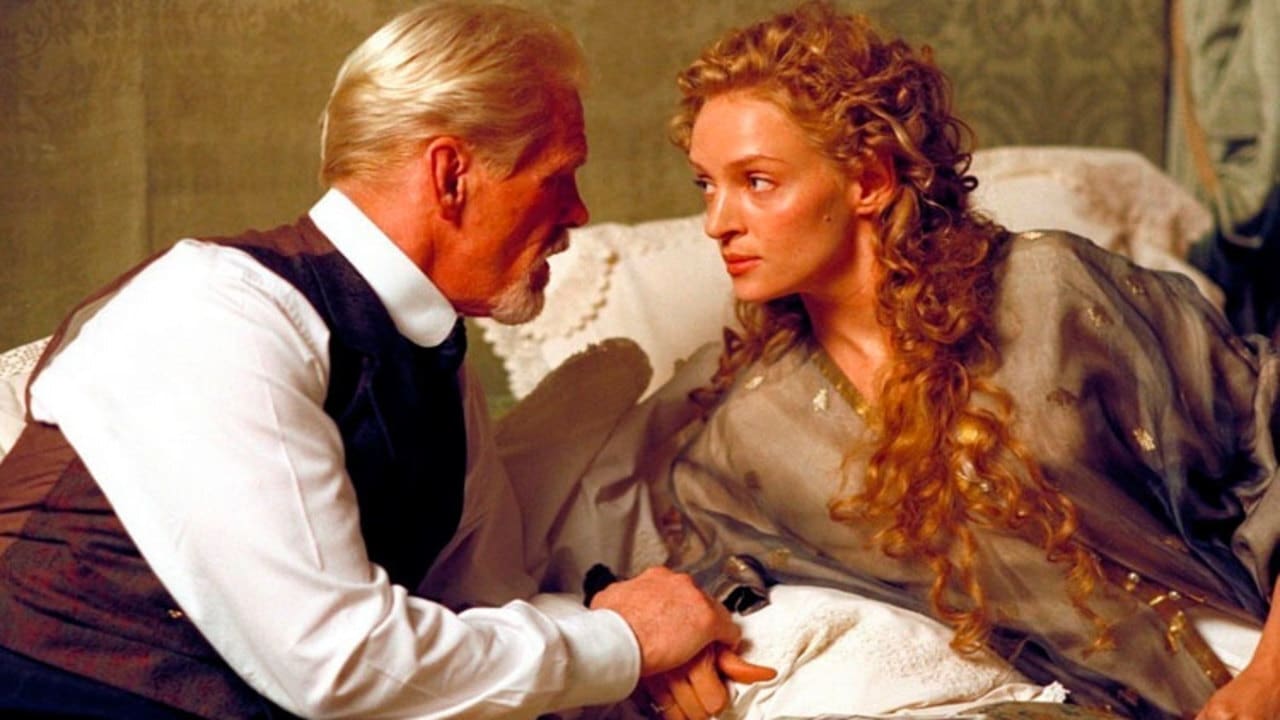

From the opening frames, you're enveloped in the signature Merchant Ivory aesthetic: opulent settings, meticulously crafted period detail, and a pervasive sense of hushed intensity. We are drawn into the intertwined lives of four wealthy expatriates and Europeans in the early 20th century. There’s the incredibly wealthy American widower Adam Verver (James Fox, bringing his characteristic understated gravitas) and his naive daughter Maggie (Kate Beckinsale). Maggie marries the charming but impoverished Italian Prince Amerigo (Jeremy Northam), while her father, in turn, marries Maggie's sophisticated, penniless friend, Charlotte Stant (Uma Thurman). The devastating complication? Amerigo and Charlotte share a secret past, a passionate affair rekindled just before their respective marriages bind them into the same tight, gilded family circle. It’s a setup ripe for the kind of emotional chess game Henry James specialized in, translated to the screen with visual grace by Ivory and his long-time collaborator, screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala.

The Weight of Unspoken Truths

What makes The Golden Bowl compelling, and perhaps challenging for some, is its focus on the nuances of concealment and gradual revelation. This isn't a story of grand confrontations, at least not initially. It's about the slow, dawning awareness, the subtle shifts in gaze, the conversations laden with double meanings. The titular golden bowl, beautiful but flawed with a hidden crack, becomes the potent symbol for the seemingly perfect marriages built on a foundation of deceit. Maggie's journey from innocent trust to quiet, steely understanding forms the narrative core. Does the film fully capture the intricate interiority of James's famously complex late novel? Perhaps not entirely – how could it? – but it masterfully conveys the emotional claustrophobia, the sense that these characters are trapped by propriety, wealth, and their own tangled desires.

Performances Forged in Silence

The success of such a film hinges significantly on the performances, and the cast here delivers interpretations steeped in careful restraint. Kate Beckinsale, transitioning here into more serious dramatic roles, carries the weight of Maggie's awakening with remarkable poise. You see the innocence drain from her eyes, replaced by a watchful intelligence. Jeremy Northam perfectly embodies the Prince's allure and his inherent weakness, a man caught between passion and pragmatism. Uma Thurman gives Charlotte a compelling blend of surface confidence and underlying vulnerability, her desperation palpable beneath the elegant facade. And veteran Anjelica Huston, as the perceptive society friend Fanny Assingham, acts almost as the audience's surrogate, observing the unfolding drama with a knowing, sometimes concerned, eye. Her presence, along with James Fox, provides a vital link to the classic Merchant Ivory ensemble feel we recognize from films like A Room with a View (1985) or Howards End (1992).

Crafting James for the Screen

Adapting Henry James is notoriously difficult; his focus often lies less in plot mechanics and more in the dense psychological landscapes of his characters. Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, who won Oscars for adapting Forster for Merchant Ivory, faced a Herculean task with one of James's most complex works. The screenplay necessarily simplifies some aspects, but it retains the essential moral ambiguities and the crushing weight of social convention. James Ivory's direction is, as ever, measured and visually precise. Cinematographer Tony Pierce-Roberts captures the suffocating beauty of the Italian palazzos and English country estates, making the settings characters in their own right. It’s worth noting this project was long in development for the Merchant Ivory team, a testament to their dedication to bringing challenging literary works to life. While perhaps lacking the immediate emotional accessibility of some of their earlier hits, the film’s commitment to its source material’s tone is admirable. It reportedly cost around $15 million – a respectable sum for a period drama then – but didn't quite achieve the breakout success of their 90s triumphs, perhaps indicating shifting audience tastes as we entered the new millennium.

Final Reflections

The Golden Bowl might not be the first Merchant Ivory film that springs to mind, perhaps overshadowed by their earlier, more celebrated adaptations. It demands patience, asking the viewer to lean in and observe the subtle currents flowing beneath the polished surface. Yet, there's a quiet power to it, a haunting quality that lingers. It feels like a mature, perhaps melancholic, meditation on themes they explored throughout their career: the complexities of love, the constraints of society, the devastating consequences of secrets. It’s a film that rewards attentive viewing, revealing more layers with each watch.

For those of us who cherished the Merchant Ivory brand on VHS, who appreciated their dedication to intelligent, beautifully crafted adult drama, The Golden Bowl serves as a poignant, perhaps slightly somber, bookend to that particular golden age. It’s a reminder of a style of filmmaking that feels increasingly rare today.

Rating: 7.5/10

Justification: While meticulously crafted and featuring strong performances, particularly from Beckinsale and Thurman, the film struggles slightly under the weight of its notoriously dense source material. The deliberate pacing, characteristic of Ivory, might test some viewers, and it doesn't quite achieve the resonant emotional impact of Merchant Ivory's absolute best work. However, its visual beauty, intelligent adaptation, and the unsettling power of its central themes make it a worthy, if demanding, watch, especially for admirers of the director-producer team and literary cinema.

Final Thought: It leaves you pondering the price of maintaining appearances, and whether a truth, once fractured, can ever truly be made whole again.