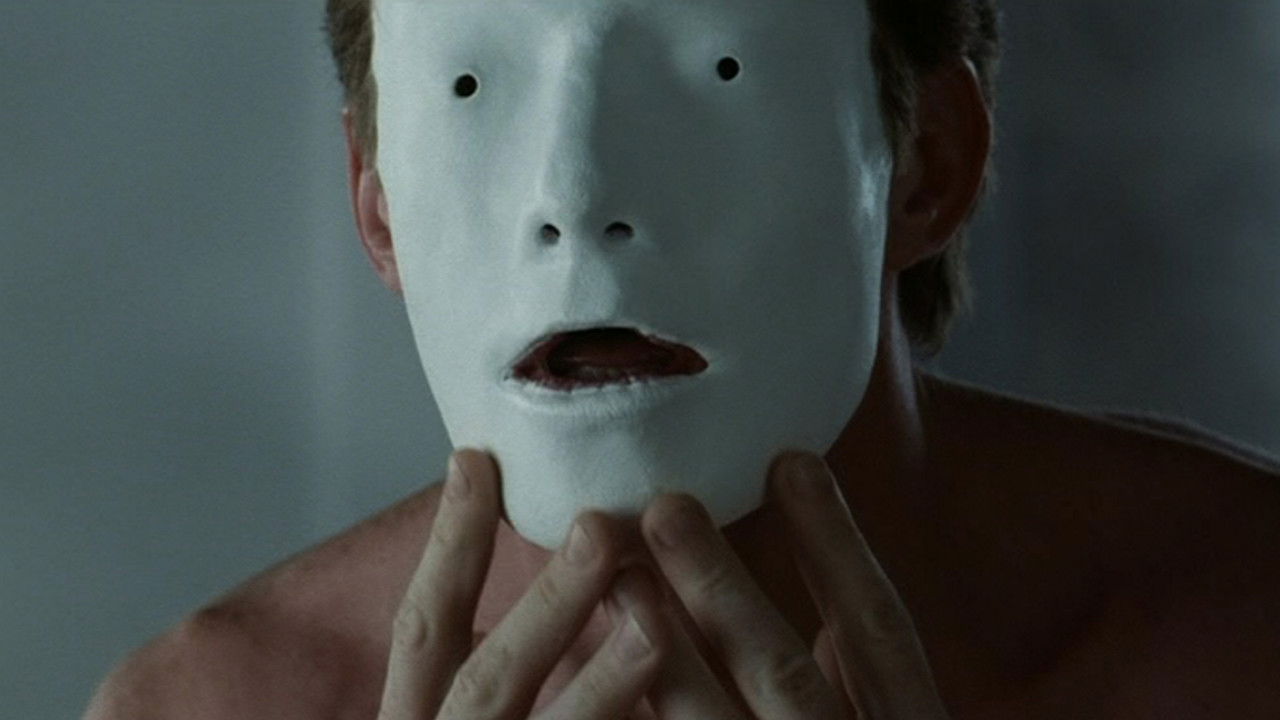

That blank, featureless white mask. It stares back from the screen, devoid of expression yet radiating a palpable sense of suppressed fury. It’s the face—or lack thereof—of Henry Creedlow, the protagonist of George A. Romero’s often overlooked 2000 chiller, Bruiser. This wasn't the Romero most fans expected at the turn of the millennium; the zombies were shelved for something arguably more unsettling: a deep dive into the dehumanizing void of modern life and the terrifying eruption of violence when identity is stripped away entirely. Watching it feels like discovering a forgotten tape tucked away behind the more prominent horror titles, a strange detour from a master filmmaker that still leaves a mark.

The Face of No One

Bruiser taps into a specific kind of dread – the quiet desperation of being invisible, unheard, and utterly powerless. Jason Flemyng plays Henry, a man working for a vapid fashion magazine called "Bruiser," who is systematically emasculated by everyone around him: his cheating wife (Leslie Hope), his embezzling best friend, and most viciously, his tyrannical, egomaniacal boss, Milo Styles. Milo, brought to life with gloriously unhinged menace by the inimitable Peter Stormare (who can forget him in Fargo?), is the embodiment of toxic power and casual cruelty. Henry is the ultimate doormat, swallowing indignities until something inside him fundamentally breaks.

The morning after a particularly humiliating party, Henry wakes to find his face replaced by a smooth, white, mannequin-like mask. It’s not on his face; it is his face. This jarring, surreal transformation isn't just physical; it's the catalyst for unleashing years of pent-up rage. The anonymity grants him a terrifying freedom. No longer Henry the victim, he becomes a vengeful cipher, methodically hunting down those who wronged him. Romero, who also penned the script, seems less interested in the how of the transformation and more in the why of the ensuing rampage. It’s a stark commentary on conformity, societal pressure, and the potential for violence lurking beneath a placid surface. Doesn't that core idea still resonate uncomfortably today?

Romero Off the Leash

Coming after a decade where Romero struggled to get projects financed following the studio interference on 1988's Monkey Shines and the mixed reception of The Dark Half (1993), Bruiser feels like a return to his more independent roots, albeit with a distinctly late-90s/early-2000s aesthetic. Shot primarily in Toronto, the film has a somewhat sterile, cold look that complements its themes of alienation. You can feel Romero wrestling with his own frustrations here, perhaps channeling them into Henry's plight and Milo's monstrous portrayal of exploitative power figures. Interestingly, Romero has mentioned that the idea stemmed partly from his own feelings of being faceless and disregarded within the film industry at times.

The production itself wasn’t without its quirks. The distinctive blank mask, designed to be utterly featureless, apparently presented Jason Flemyng with a significant acting challenge, forcing him to convey a whirlwind of emotions purely through body language. It’s a testament to his performance that Henry remains a compelling, if deeply disturbed, figure even without facial expressions for much of the runtime. And for punk rock fans, keep an eye out for the cameo by legendary horror-punk band The Misfits, performing at Milo's party – a suitably chaotic touch for the film’s atmosphere. They even contributed a track, "Fiend Without a Face," to the soundtrack.

A Different Kind of Horror

While Bruiser delivers moments of brutal, bloody violence as Henry enacts his revenge, its primary horror is psychological. The dread builds not from jump scares, but from the chillingly relatable premise of being pushed too far. The practical effects surrounding the mask and the subsequent violence are effective, grounded in a pre-CGI era sensibility that feels tactile and visceral, reminiscent of the effects work Romero championed in his earlier films. The film doesn't quite achieve the iconic status of his Dead trilogy, lacking perhaps their raw, groundbreaking energy, but it offers a different flavour of Romero – more introspective, more focused on internal monsters than external ones.

The pacing can feel a little uneven, lingering perhaps too long in setting up Henry's miserable existence before the transformation kicks the plot into high gear. Peter Stormare threatens to steal the entire film with his larger-than-life performance, which is immensely entertaining but occasionally overshadows Flemyng's more subdued (by necessity) central role. Yet, the core concept remains potent, a dark fable about identity and vengeance in a world that often seems determined to erase individuality. It captures that specific late-night, slightly surreal vibe that many direct-to-video releases of the era possessed. I remember finally catching this on cable years after its quiet release, expecting zombies, and being completely thrown – in a good way – by this stark, angry psychological piece.

Final Verdict

Bruiser isn't peak Romero, but it's a fascinating, often unnerving entry in his filmography that deserves more attention than it typically receives. It’s a film born of frustration, exploring dark corners of the human psyche with a bleak, unflinching gaze. Its central metaphor is powerful, and the performances, particularly Stormare's scenery-chewing turn and Flemyng's physically demanding role, are memorable. While some aspects feel dated to the specific anxieties of the late 90s/early 2000s corporate culture, the underlying fear of losing oneself remains timeless.

Rating: 6.5/10

Justification: Bruiser scores points for its bold central concept, Romero's willingness to explore psychological horror, Flemyng's committed performance under challenging circumstances, and Stormare's unforgettable villain. However, it's held back slightly by uneven pacing in the first act and a visual style that, while fitting, lacks the enduring iconic quality of Romero's best work. It doesn't quite reach the heights of his classics but offers a compelling, dark, and thought-provoking experience that feels distinct within his catalogue.

It’s a potent reminder that sometimes the most terrifying mask isn't one you put on, but the one you can’t take off – or the one society forces upon you until you simply disappear. A grim, worthwhile discovery for Romero completists and fans of turn-of-the-millennium psychological thrillers.