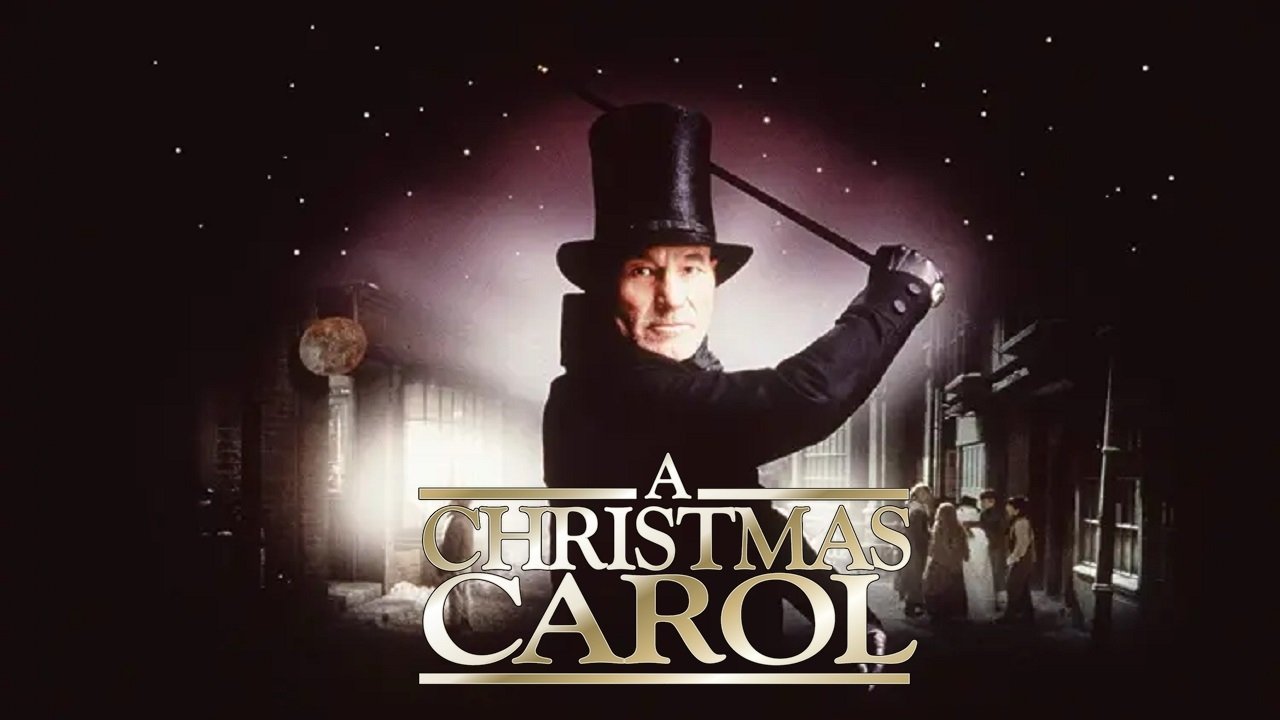

There’s a certain chill that settles in the air when contemplating the sheer volume of adaptations Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol has inspired. It's a story so foundational, so deeply etched into our collective consciousness, particularly around the holidays, that each new version arrives carrying the weight of all those that came before. Yet, some manage to carve out their own distinct space, not by radical reinvention, but by the sheer force of performance and a commitment to the source material’s inherent darkness. The 1999 television film, anchored by a truly formidable Patrick Stewart, is precisely one such rendition, a version that feels less like a cozy yuletide fable and more like a stark, necessary confrontation with a frozen soul.

### A Frost on the Window Pane

Directed by David Jones (whose work often graced the stage and thoughtful television drama) and penned by Peter Barnes, this adaptation, originally produced for TNT, doesn't shy away from the grim realities of Victorian London or the profound bitterness of Ebenezer Scrooge. Filmed primarily at Ealing Studios in the UK, there's a tangible weight to the production design – the cobbled streets feel damp and cold, the counting house suitably oppressive, the poverty starkly rendered. It leans away from the more whimsical interpretations, opting for a grounded, almost theatrical realism that allows the supernatural elements, when they arrive, to feel genuinely intrusive and unsettling. This isn't the brightly lit Christmas card version; it's closer to the ghostly warning Dickens intended.

### The Weight of Regret, Embodied

At the absolute heart of this film lies Patrick Stewart's towering performance as Scrooge. Many actors have donned the nightcap, but Stewart brings a unique gravity, honed perhaps by years performing a one-man stage version of the story, which directly led to this production. His Scrooge isn't merely grumpy or miserly; he is a man encased in ice, brittle with repressed grief and hardened by decades of self-imposed isolation. Stewart masterfully portrays the intellectual arrogance Scrooge uses as a shield, the clipped, precise delivery conveying a man who believes he has reasoned his way into wretchedness. What makes his portrayal so compelling is the subtle flicker of vulnerability beneath the permafrost – a haunted look in his eyes during Marley's visitation, a tremor of long-forgotten warmth when confronted by the Ghost of Christmas Past (Joel Grey, bringing an ethereal, almost childlike strangeness to the role). Stewart wasn't just playing Scrooge; he inhabited the man's profound loneliness, making the eventual thaw feel earned and deeply moving rather than simply inevitable. His performance rightly earned him a Screen Actors Guild Award nomination, a testament to its power.

### Shadows and Supporting Souls

The supporting cast effectively orbits Stewart’s central performance. Richard E. Grant, an actor always capable of finding nuance, presents a Bob Cratchit who is certainly humble and kind, but also possesses a quiet dignity. He isn’t just a caricature of meekness; you feel the weight of his anxieties for Tiny Tim and the genuine, albeit strained, respect he holds for his difficult employer. The spectral visitations are handled with a focus on psychological impact rather than overt spectacle. Marley’s Ghost (Bernard Lloyd) is genuinely chilling, bound in spectral chains forged of his own avarice, and the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come remains the classically terrifying, silent phantom. The effects, a mix of practical work and late-90s digital flourishes, might show their age slightly compared to modern blockbusters, but they serve the story effectively, prioritizing atmosphere over flashy distraction. Remember, 1999 was a time when CGI was becoming more accessible for television, but still often used with a certain restraint, which arguably benefits the ghostly, less corporeal nature of these spirits.

### Not Just Humbug, But Harsh Truths

What perhaps distinguishes this Christmas Carol most is its willingness to sit with the story’s darker implications. It doesn't rush towards the redemption arc but dwells on the consequences of Scrooge's choices – the isolation, the fear he inspires, the opportunities for connection squandered. The sequence with the Ghost of Christmas Present, revealing Ignorance and Want, carries a particular allegorical weight here, feeling less like a brief aside and more like a direct indictment of societal neglect. Doesn't this unflinching look at the human cost of indifference feel particularly resonant, even decades later? It forces a reflection on whether we heed the warnings any better than Scrooge initially did. This version reminds us that the transformation isn't just about finding festive cheer; it's about recognizing shared humanity and the responsibility that comes with it.

I recall getting this one on VHS shortly after it aired, perhaps renting it from the local Blockbuster. It felt different from the versions I grew up with – less overtly sentimental than the Alastair Sim classic, grittier than the Muppet rendition. It felt… serious. And watching it again now, that seriousness, anchored by Stewart's phenomenal work, is its greatest strength. It treats Dickens' text with immense respect, mining its emotional depths and moral complexities.

Rating: 8.5/10

This score reflects the film's standout central performance, its atmospheric fidelity to the source material's tone, and its overall effectiveness as a powerful, mature adaptation. While perhaps lacking the visual flair of bigger-budget versions and showing some signs of its TV movie origins and late-90s effects, Patrick Stewart's definitive Scrooge elevates it significantly. It stands as a potent and moving interpretation that prioritizes psychological truth over festive spectacle.

For those seeking a Christmas Carol that truly grapples with the darkness before embracing the light, this 1999 version remains a compelling and deeply felt rendition, a phantom limb of Christmas Past that still carries a significant emotional weight.