Okay, fellow travelers on the magnetic tape highway, settle in. Turn down the lights. Remember that specific hum the VCR made? That slight fuzz on the rented copy? Tonight, we're diving headfirst into a stretch of celluloid road that offers no easy exits, only hairpin turns into the darkest corners of the psyche: David Lynch's 1997 fever dream, Lost Highway. This isn't just a movie; it's an experience, a feeling that crawls under your skin and stays there, buzzing like bad electricity long after the credits roll and the tape auto-rewinds with a clunk.

The opening image itself is pure, distilled dread: headlights cutting through absolute blackness, hurtling down a highway devoid of landmarks or destinations. It’s the perfect visual metaphor for the journey ahead. We meet Fred Madison (Bill Pullman, playing brilliantly against his usual affable type), a jazz saxophonist living in a stylishly sterile Los Angeles home with his enigmatic wife, Renee (Patricia Arquette). Their relationship crackles with unspoken tensions, a silence thick with things unsaid. Then, the videotapes start arriving. Anonymous, unsettling glimpses of their own house, creeping closer, eventually revealing them asleep in their bed. Who’s filming? How are they getting in? The paranoia mounts, thick and suffocating, until Fred finds himself plunged into a nightmare he can’t wake up from.

A Road Paved with Nightmares

This is David Lynch territory, so forget linear narrative. Forget easy answers. Lost Highway, co-written with Barry Gifford (whose novel inspired Lynch's Wild at Heart (1990)), operates on dream logic, or more accurately, nightmare logic. It's less a story told than a mood sustained – a state of perpetual anxiety and fractured identity. Lynch reportedly got the title phrase from Gifford and was fascinated by the concept of a "psychogenic fugue," a dissociative state triggered by extreme stress where one can lose awareness of their identity. That idea permeates every frame. The first half, drenched in shadows and scored by Angelo Badalamenti's signature ominous jazz and unsettling synths, is a masterclass in building tension. Pullman conveys Fred's mounting terror with chilling conviction; you feel his world dissolving around him.

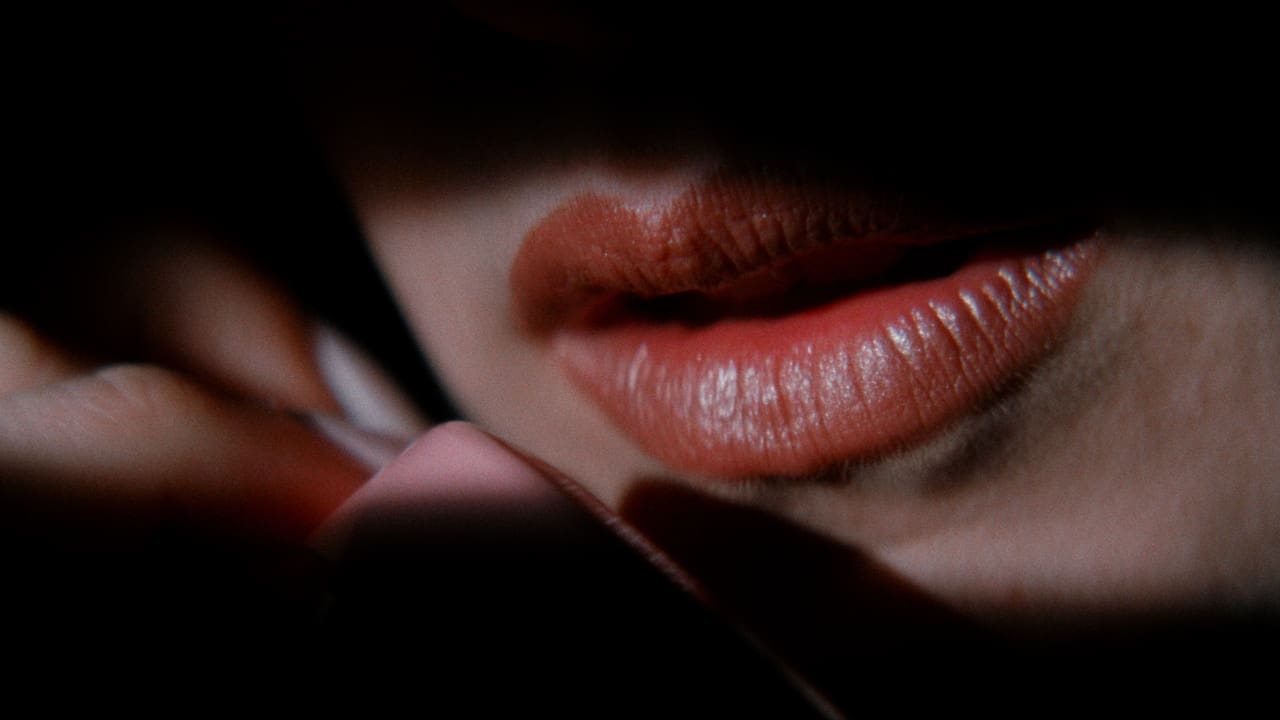

Then comes the shift. Abrupt. Disorienting. Fred seemingly transforms – or is replaced – in his prison cell by Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty), a young auto mechanic who has no memory of how he got there. Released, Pete returns to his life, inevitably falling under the spell of the dangerously alluring Alice Wakefield – also played by Patricia Arquette, now a blonde femme fatale tangled with the menacing gangster Mr. Eddy (an unforgettably volatile Robert Loggia). Is Alice Renee? Is Pete Fred? The questions pile up, deliberately left unanswered, forcing the viewer into a state of active interpretation, much like trying to decipher a disturbing dream upon waking.

Faces in the Static

The performances are key to navigating this labyrinth. Pullman is exceptional, shedding his everyman persona for something brittle and desperate. Getty captures Pete's youthful confusion and recklessness effectively. But it's Patricia Arquette who truly anchors the film's duality. Her shift from the dark-haired, passive Renee to the blonde, assertive Alice is mesmerizing and central to the film's Mobius strip narrative. She embodies the shifting desires and dangers that haunt the male protagonists.

And then there's the Mystery Man. Played by the late Robert Blake with a Kabuki-like intensity (Lynch apparently told him to base the character on a recurring nightmare Blake himself had described), he's one of cinema's most genuinely unnerving figures. That rictus grin, the stark white makeup, the impossible phone call – "I'm there right now. At your house. Call me." – it’s pure, undiluted nightmare fuel. His appearances punctuate the film with moments of surreal terror that defy logical explanation but resonate on a primal level. Blake's later real-life notoriety adds an uncomfortable, unintended layer of darkness when revisiting the film today, a strange echo of the unsettling energy he projects on screen.

Sounds from the Abyss and Shadow Plays

Beyond the narrative enigma, Lost Highway is an audiovisual feast. Peter Deming's cinematography uses deep shadows and stark contrasts to create a world that feels both real and dreamlike. The infamous burning cabin scene in the desert, filmed near Death Valley (like parts of Eraserhead), is hauntingly beautiful and terrifying. The production design emphasizes claustrophobic interiors and desolate exteriors, amplifying the sense of isolation and dread.

The soundtrack, famously co-produced by Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails, is integral. While Badalamenti provides the Lynchian atmospherics, Reznor curated contributions from artists like Rammstein ("Heirate Mich," "Rammstein"), Marilyn Manson ("Apple of Sodom"), and Smashing Pumpkins ("Eye"), alongside his own driving track "The Perfect Drug." This potent mix of industrial rock, dark ambient, and unsettling jazz perfectly complements the film's fractured psyche and modern noir feel. It became a hit album in its own right, introducing many to Lynch's world through music. It’s one of those soundtracks that instantly transports you back to the film's specific brand of late-90s dread.

Was It All Just a Dream on Tape?

Watching Lost Highway back in the day, probably late at night on a slightly worn VHS rented from Blockbuster or the local independent store, felt like discovering a secret transmission. It wasn't like other thrillers. It didn't spoon-feed you plot points. It demanded engagement, invited speculation, and often left you feeling deeply unsettled without quite knowing why. Did you rewind certain scenes, trying to piece together the impossible chronology? I certainly remember the confusion mingling with fascination. Its initial critical reception was polarized, and its US box office ($3.7 million against a $15 million budget) wasn't stellar, but its power wasn't in mainstream appeal. It was destined for cult status, debated and dissected by fans who appreciated its audacious ambiguity.

Lost Highway isn't a film for everyone. It's challenging, oblique, and refuses easy closure. But for those attuned to David Lynch's wavelength, it’s a potent and unforgettable exploration of guilt, jealousy, fractured identity, and the inescapable consequences of one's actions, all wrapped in a stylish, terrifying package. It’s a film that truly feels like it could only have emerged from the dark corners of the 90s indie film scene, pushing boundaries and haunting video store shelves.

VHS Heaven Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's masterful creation of atmosphere, its unforgettable imagery and sound design, compelling performances (especially Arquette and Blake), and its status as a unique, uncompromising piece of Lynchian art. It’s a near-perfect execution of its nightmarish vision, losing perhaps a single point only for its sheer impenetrability, which, while intentional, can be a barrier for some viewers expecting a more conventional narrative resolution.

Final Thought: Lost Highway remains a potent dose of cinematic dread, a puzzle box where the unsettling journey itself is the destination. It’s a film that reminds you that sometimes, the most terrifying place isn't a haunted house, but the dark, uncharted highways of the human mind.