There’s a particular kind of frantic energy that thrums just beneath the surface of certain city nights, a desperation fueled by dreams too big and pockets too empty. It’s a feeling captured with unsettling vibrancy in Irwin Winkler’s 1992 reimagining of Night and the City, a film that, much like its restless protagonist, seems perpetually striving, reaching, and occasionally stumbling under the weight of its own ambitions. Watching it again after all these years, slipping that well-worn tape into the VCR felt less like revisiting a blockbuster memory and more like unearthing a potent, slightly bruised artifact of early 90s New York grit.

### The Hustler's Heartbeat

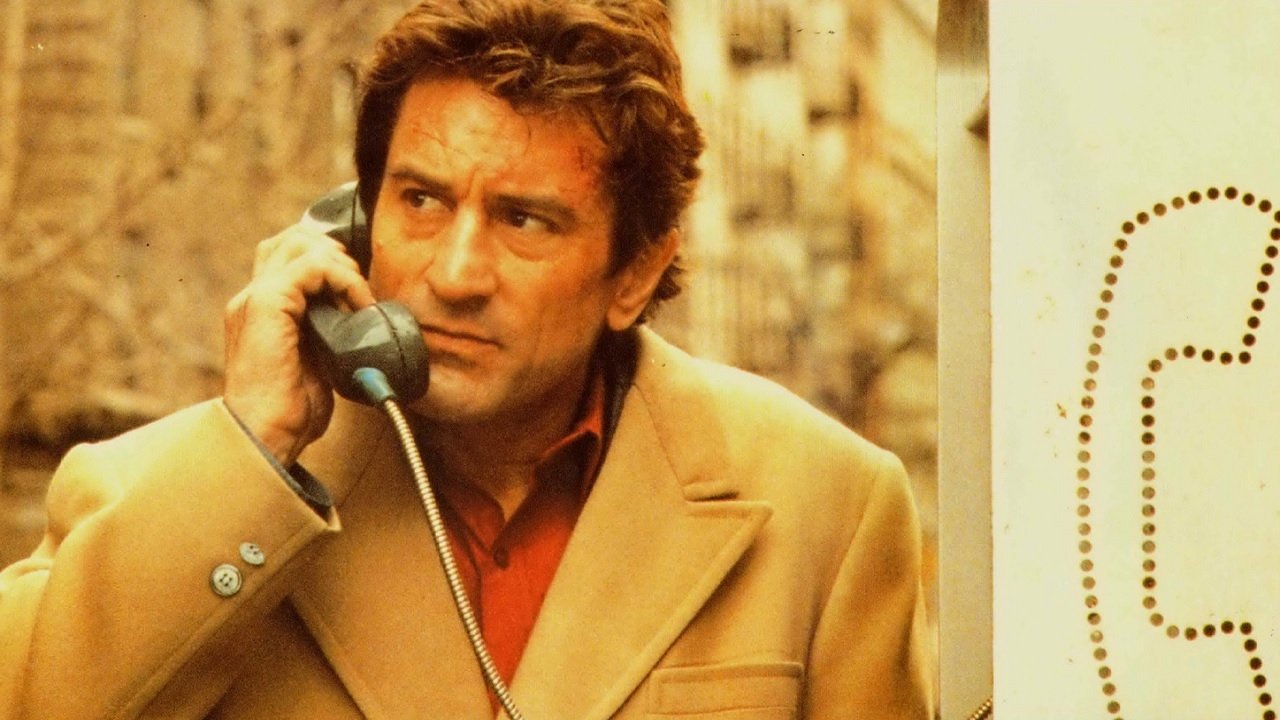

At the pulsing, often arrhythmic heart of the film is Harry Fabian, embodied by Robert De Niro with a relentless, almost exhausting velocity. This isn't the cool, calculated menace of his gangster roles; Fabian is a small-time lawyer, a perpetual motion machine of half-baked schemes and desperate handshakes, chasing the elusive Big Score that always seems just beyond his grasp. De Niro, who was deep into his run of exploring complex, often morally ambiguous characters (Goodfellas (1990) was still fresh in memory), pours everything into Fabian. You see the flop sweat, the forced smile that doesn't quite reach the eyes, the frantic calculations clicking behind his gaze. It’s a performance that borders on uncomfortable, forcing us to confront the raw, unglamorous reality of someone constantly scrambling on the edge of ruin. Does his desperate optimism mask a profound self-delusion, or is there a flicker of genuine, albeit misguided, hope in his hustle?

It's fascinating to learn that Winkler, a legendary producer finally stepping behind the camera for his directorial debut here, had worked with De Niro extensively, notably on Raging Bull (1980). That pre-existing relationship likely allowed for the kind of intense, character-driven exploration we see in Fabian. This wasn't just another star vehicle; it felt like a deep dive into a specific type of urban desperation, channeled through an actor firing on all cylinders.

### Weary Souls in Neon Glow

Counterbalancing Fabian’s manic energy is Helen Nasseros, played with a profound, soulful weariness by Jessica Lange. Helen runs the bar owned by her husband Phil (the formidable Cliff Gorman), a gathering spot for the city’s hustlers and dreamers, and she carries the weight of unspoken disappointments and fragile hopes. Lange, always brilliant at conveying complex inner lives (Tootsie (1982), Blue Sky (1994)), imbues Helen with a quiet dignity that anchors the film. Her connection with Fabian is fraught with ambiguity – is it genuine affection, shared loneliness, or simply proximity in a world that feels increasingly cold? Their scenes together crackle with unspoken tension, a fragile island of potential warmth in Fabian’s turbulent sea.

And then there’s Cliff Gorman as Phil Nasseros. Gorman, perhaps best known to some for his Tony-winning stage work or his role in The Boys in the Band (1970), is absolutely electric here. Phil isn't just a cuckolded husband; he's a coiled spring of resentment and wounded pride, his smiles thin, his threats veiled but potent. The scenes where Phil confronts Fabian, particularly those concerning Fabian's ill-fated foray into boxing promotion, are masterclasses in simmering menace.

### Updating Noir for a New Decade

Based on the 1950 noir classic directed by Jules Dassin and Gerald Kersh's novel, this version, scripted by the great chronicler of urban life, Richard Price (The Color of Money (1986), Clockers (1995)), transplants the action from London to a distinctly pre-gentrification New York City. Price's ear for dialogue is, as always, impeccable, capturing the rhythms and anxieties of its characters. The world Fabian navigates – the smoky bars, the dingy law offices, the underbelly of the boxing world – feels lived-in and authentic, a far cry from the glossier depictions of the city often seen in the era.

Winkler’s direction emphasizes this grit. The cinematography often feels close, almost claustrophobic, mirroring Fabian's increasingly tight circumstances. It’s not a flashy film visually, but it effectively uses the city itself – its shadowed alleys, neon signs reflecting on wet pavement, the constant hum of unseen activity – as a character. One fascinating production tidbit is that the film struggled to find an audience upon release, grossing only around $6.2 million against a budget estimated near $18-20 million. It seemed audiences perhaps weren’t ready for this kind of downbeat, character-driven drama amidst the action blockbusters and rising indie darlings of the early 90s. It found its second life, like so many interesting films of the era, on home video – a discovery waiting on the shelf at Blockbuster.

### Echoes in the Asphalt Jungle

While the film captures the specific anxieties of its time – the sense of economic precariousness, the fading remnants of old neighborhood power structures – its themes resonate beyond the early 90s. Fabian's desperate pursuit of relevance, his belief that one big win can erase a lifetime of small failures, feels eternally human, if tragically misguided. What does it mean to chase a dream so hard you lose sight of everything else? The film doesn't offer easy answers, presenting Fabian not as a hero or a villain, but as a deeply flawed man caught in a cycle of his own making.

The boxing subplot, Fabian's grand scheme to become a promoter, feels like a perfect metaphor for his entire existence – chaotic, driven by ego, and ultimately destined to blow up in his face. The fight scenes themselves aren't stylized; they feel messy and brutal, reflecting the ugly realities underlying Fabian's ambitions.

Rating: 7/10

This rating reflects a film powered by phenomenal central performances, particularly from De Niro and Lange, and steeped in a palpable, gritty atmosphere courtesy of Winkler's direction and Price's sharp script. It successfully translates the core despair of noir to a then-contemporary setting. However, its relentless bleakness and Fabian’s often abrasive nature can make it a challenging watch, and it perhaps doesn't quite escape the shadow of its esteemed 1950 predecessor or other towering NYC dramas of the period. It remains a compelling, often overlooked piece of early 90s cinema, a potent reminder of the desperation that can flicker behind the bright city lights.

What lingers most powerfully after the tape clicks off isn't a specific plot point, but the feeling – that frantic, hungry energy of Harry Fabian, a ghost forever haunting the neon-washed streets of a New York that itself feels like a fading memory.