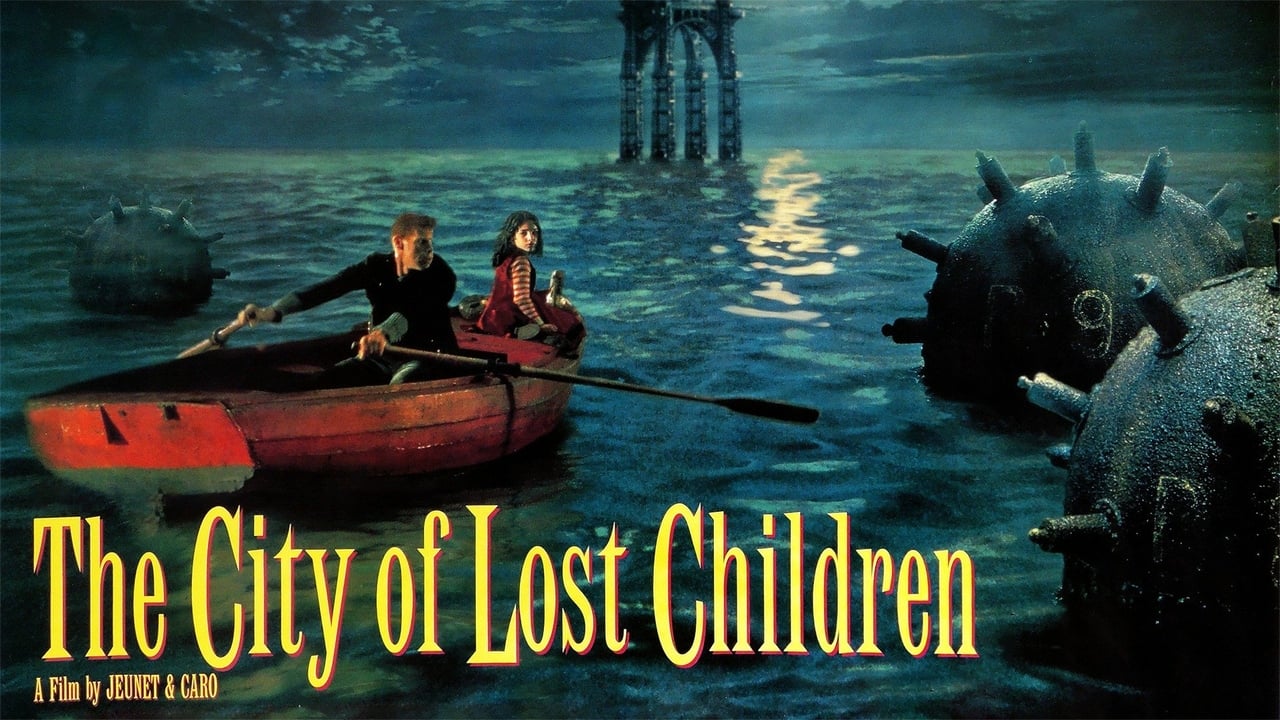

The green-tinged fog never really lifts, does it? Not from that nameless, perpetually rain-slicked port city where childhood dreams are literally being stolen. The City of Lost Children (1995) wasn't just another tape on the rental shelf; it felt like discovering a forbidden frequency, a transmission from a world operating on nightmare logic and powered by coal smoke and sorrow. Finding this surreal French masterpiece, nestled perhaps between a familiar blockbuster and a slasher sequel, was like unearthing a bizarre artifact, its cover art hinting at a darkness far stranger than your average horror flick.

A Labyrinth of Longing

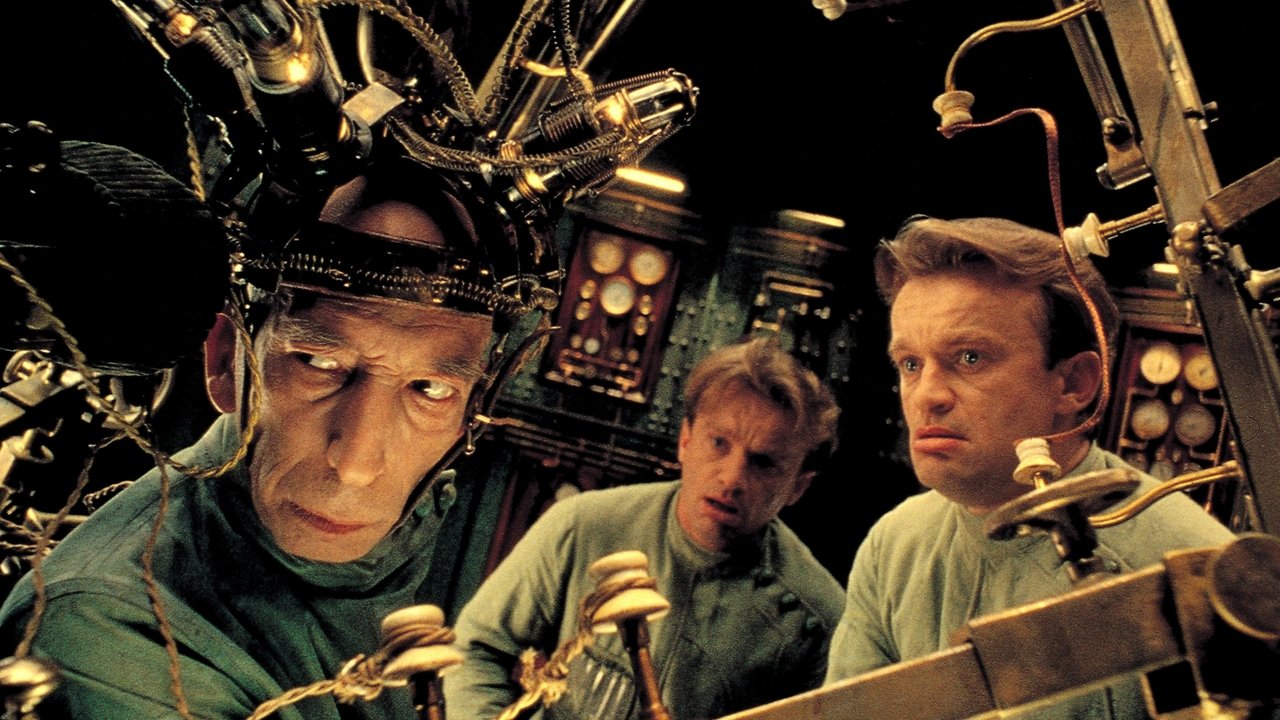

Directed by the visionary duo of Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet, who previously gave us the equally eccentric Delicatessen (1991), this film plunges us headfirst into a world suffocating under its own peculiar grime. Somewhere offshore, aboard a rusting rig shrouded in mist, lives Krank (Daniel Emilfork, whose cadaverous visage and chilling voice are unforgettable). A tormented creation prematurely aged and incapable of dreaming, Krank commissions his bizarre brethren – a cadre of identical, narcoleptic clones and a sardonic talking brain in a tank – to kidnap local children, hoping to siphon their dreams and stave off his own rapid decay. The premise alone feels like something dredged from the subconscious, a Brothers Grimm tale filtered through seawater and rust.

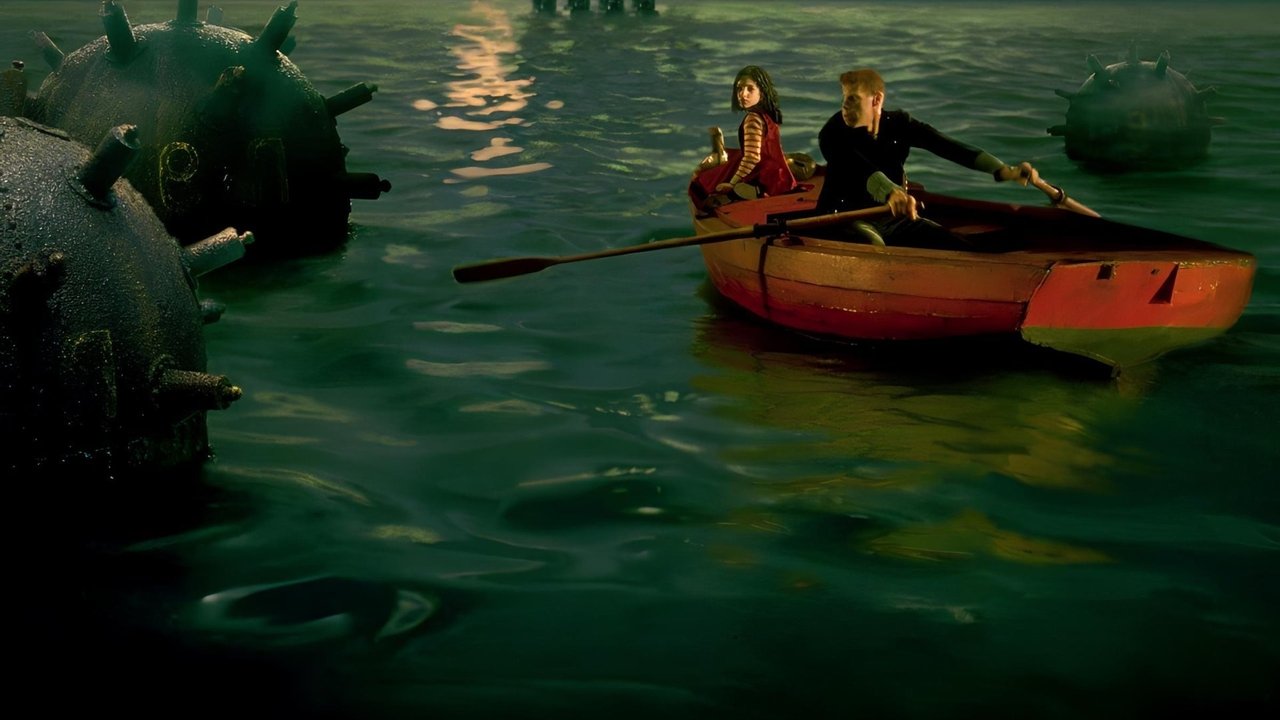

When Denree, the adopted younger brother of circus strongman One (Ron Perlman), is snatched, One embarks on a desperate search. He teams up with the fiercely independent Miette (Judith Vittet), a street-smart orphan leading a gang of child thieves under the exploitative thumb of the conjoined "Octopus" sisters. Their journey through the city's underbelly is a descent into a phantasmagoria of bizarre characters and unsettling locations: the murky docks, the headquarters of the cyclopean cult (whose members trade eyes for electronic replacements), and ultimately, Krank's labyrinthine fortress of stolen innocence.

Steam, Sweat, and Tears

What truly sears The City of Lost Children into memory is its astonishing visual tapestry. Caro, primarily focused on the art direction, and Jeunet, handling the actors and narrative flow, created a world that feels utterly unique yet disturbingly tangible. The colour palette – dominated by sickly greens, ochres, and deep shadows – evokes decay and enchantment simultaneously. Every frame is dense with detail: intricate, Rube Goldberg-esque contraptions, bizarre costumes that seem organically fused with their wearers, and sets that feel both impossibly grand and claustrophobically oppressive. Angelo Badalamenti's haunting score, reminiscent of his work with David Lynch, perfectly complements the visuals, weaving a melancholic spell that lingers long after the credits roll.

The practical effects and miniature work, hallmarks of the pre-CG era, are breathtaking. Krank's oil rig lair, the complex dream-harvesting machine, the trained fleas – these elements possess a weight and texture that digital effects often struggle to replicate. Remember how real those intricate sets felt back then, even viewed through the fuzzy lens of a CRT? It was a kind of dark magic, demanding a suspension of disbelief that felt earned. The film reportedly cost around $18 million, a significant sum for a French production at the time, and every centime feels visible on screen, poured into crafting this singular vision.

Faces in the Fog

The performances are as distinctive as the visuals. Ron Perlman, a familiar face even then perhaps from Beauty and the Beast (1987-1990) or The Name of the Rose (1986), brings a soulful vulnerability to the strongman One. A fascinating tidbit: Perlman didn't speak French and learned all his lines phonetically for the role, a testament to his commitment and adding an almost subconscious layer to his character's outsider status. Young Judith Vittet is remarkable as Miette, portraying a resilience and world-weariness far beyond her years. But it’s Daniel Emilfork as Krank who truly haunts. His performance is a masterclass in restrained anguish and unsettling otherness; his face alone seems to tell a story of centuries of sorrow and scientific hubris gone wrong.

The supporting cast, from the bumbling clones to the sinister Irvin (the aforementioned brain voiced by Jean-Louis Trintignant), populates this world with figures pulled from a fever dream. They contribute to the film’s unsettling atmosphere, where normalcy feels like a distant, forgotten concept. The Cyclops cult, with their eerie devotion and unsettling self-mutilation in the name of enhanced perception, remains one of the film's most potent and disturbing creations. Doesn't that imagery still feel unnerving?

A Dream That Won't Fade

The City of Lost Children isn't an easy film. Its narrative logic is dreamlike, sometimes elliptical, demanding attention and immersion. It doesn't offer simple scares but rather a pervasive sense of unease, a deep melancholy for lost innocence and the desperate, monstrous things beings will do to recapture or replace what they lack. It explores themes of exploitation, the subjective nature of reality, and the creation of unconventional families in the face of overwhelming darkness.

Its influence can be seen in the wave of dark fantasy and steampunk aesthetics that followed in the late 90s and beyond. While perhaps not as widely known as Delicatessen, it stands as a more ambitious, arguably darker, and visually richer counterpart. Watching it again on a modern screen, the artistry is undeniable, but there was something special about experiencing its dense, weird beauty spooling out from a VHS tape late at night, the hum of the VCR a quiet companion to the on-screen strangeness. It felt like a secret handshake among cinephiles who appreciated the bizarre and the beautiful in equal measure.

VHS Heaven Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's breathtaking visual artistry, its wholly unique atmosphere, strong performances, and unforgettable world-building. It’s a near-masterpiece of surrealist fantasy, only slightly held back by a plot that occasionally feels secondary to the spectacle. The sheer audacity and creative vision on display are undeniable. The City of Lost Children remains a potent, unsettling dream – a complex, melancholic fairy tale for adults that proved French cinema could conjure worlds as strange and immersive as any Hollywood blockbuster, leaving a residue of beautiful unease long after the screen goes dark. It's a film that truly feels made, crafted with obsessive care, a quality that resonates deeply in our increasingly digital age.