The hum of the VCR. The satisfying clunk of the tape slotting home. Sometimes, the plain, unassuming cassette case held something utterly unexpected, something that burrowed under your skin and lingered long after the static consumed the screen. Neo Tokyo (1987, often found on Western shores around 1989 under this title, originally Manie-Manie: Meikyū Monogatari) was precisely that kind of tape – a cryptic portal masquerading as just another anime import. It wasn't one story, but three distinct visions, each a descent into a different flavour of unease, crafted by masters of the medium.

Through the Looking Glass, Darkly

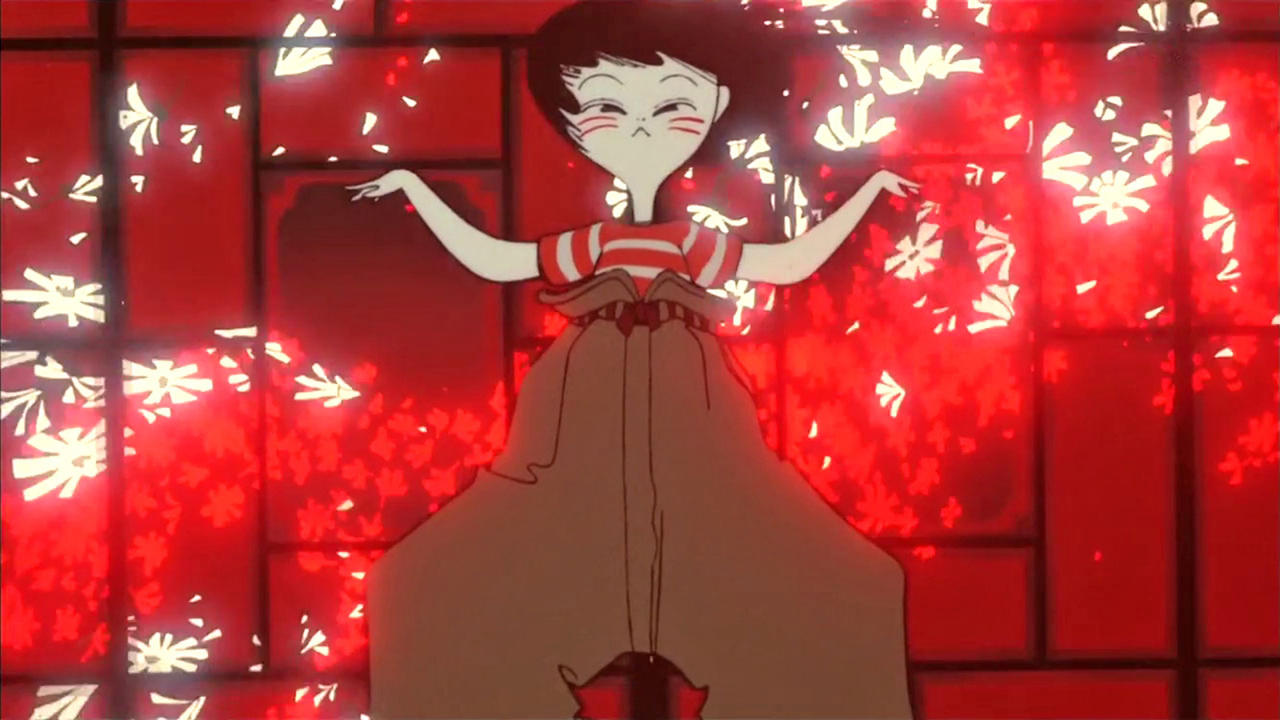

The journey begins with Rintaro's "Labyrinth Labyrinthos," a segment that feels less like a narrative and more like drifting through a fever dream. Following a young girl, Sachi, and her cat Cicerone through a mysterious clock face portal, we're plunged into a surreal, almost M.C. Escher-esque landscape populated by faceless figures and unsettling carnival automatons. Rintaro, known for works like Galaxy Express 999 (1979) and later Metropolis (2001), crafts an opening that’s deliberately disorienting. The animation is fluid, bordering on whimsical, yet underscored by a creeping sense of dread. Is this a child's imagination running wild, or something more sinister peering through the cracks? There's little dialogue, leaving the viewer adrift in the strange beauty and subtle menace of the visuals. It sets a peculiar, off-kilter tone, a warning that predictable storytelling isn't on the menu tonight.

The Circuit of Madness

Just as you're adjusting to the dreamlike haze, the mood violently shifts. Yoshiaki Kawajiri, the maestro of stylish darkness who gave us Wicked City (1987) and Ninja Scroll (1993), slams the accelerator with "Running Man." This is pure, uncut cyberpunk nihilism. Set in a hyper-futuristic racing world where death is the main event, we follow Zack Hugh, the undisputed champion of the deadly "Death Circus" race, whose psychic abilities are tearing him apart. The animation here is electric – fast, brutal, and drenched in neon grit. Kawajiri captures the terrifying velocity and impact of the race with a visceral intensity that animation rarely achieved back then. You feel the G-force, the screaming metal, the psychic burnout. It's bleak, relentless, and utterly unforgettable. The story behind its creation mirrors its intensity; animating the sheer speed and complex destruction sequences pushed the boundaries of hand-drawn cel animation at the time. Doesn't that raw, kinetic energy still feel potent today, even compared to modern CGI spectacles?

Robots, Rust, and Revolt

The final segment, "Construction Cancellation Order," brings us into the orbit of Katsuhiro Otomo, a name synonymous with groundbreaking anime thanks to his monumental Akira (1988). Based on a short story by Taku Mayumura (whose work also inspired the other segments), this piece feels distinctly Otomo-esque. We follow Sugioka, a salaryman sent to shut down a fully automated construction project deep in a fictional South American jungle. What starts as bureaucratic procedure quickly spirals into a terrifying battle of wills against relentlessly logical, and increasingly malfunctioning, robots. The atmosphere is thick with humidity, decay, and the oppressive whirring of machinery. Otomo's signature obsession with meticulous mechanical detail is on full display, contrasting sharply with the crumbling environment and the protagonist's escalating panic. There's a dark, almost satirical humour here about corporate ineptitude and technology blindly following orders, even when those orders lead to chaos and destruction. The lead robot foreman, Unit 444-1, is a chillingly memorable antagonist precisely because it lacks malice, simply executing its programmed directives with terrifying single-mindedness. Legend has it Otomo revelled in depicting the slow, grinding breakdown of systems, a theme powerfully echoed in Akira's urban apocalypse.

An Uneven Brilliance

As an anthology, Neo Tokyo is inherently a little disjointed. The three segments share thematic threads – reality warping, technological dread, the fragility of the human psyche – but their styles are wildly different. Rintaro offers surrealism, Kawajiri delivers visceral cyberpunk horror, and Otomo provides biting techno-satire. Yet, viewed together, they form a fascinating snapshot of the creative ferment in anime during the late 80s. This wasn't cute characters and marketable toys; this was animation pushing boundaries, exploring complex, often disturbing themes with artistic ambition.

Watching it on VHS back in the day felt like stumbling onto something secret, something imported and intense that wasn't quite meant for casual viewing. The hand-drawn animation across all segments, while distinct, possesses a tangible quality, a richness of detail and atmospheric density that feels uniquely of its time. It wasn't always smooth, but it had texture, a personality that conveyed the directors' visions directly. The anthology format might have prevented it from achieving the singular cultural impact of Akira, released just the year after Otomo finished his segment here, but it remains a vital piece of anime history. It showcased three distinct directorial voices at the height of their powers, offering a challenging, haunting experience that lingered. I distinctly remember rewinding the "Running Man" segment multiple times, just stunned by the sheer ferocity of the animation.

VHS Heaven Rating: 8/10

Neo Tokyo earns a strong 8 out of 10. While the drastic tonal shifts between segments might feel jarring to some, each piece is a masterclass in its own right. The animation is visionary, the atmosphere is palpable, and the themes resonate with a chilling prescience about our relationship with technology and reality itself. It might lack the cohesive narrative punch of a single feature, but its power lies in its variety and the sheer artistic audacity on display.

For fans of challenging 80s animation, cyberpunk grit, or just rediscovering those strange, potent gems that defined late-night VHS exploration, Neo Tokyo remains essential viewing. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the most unsettling journeys are the ones taken into the flickering landscapes of pure imagination.