It arrives less like a film and more like a transmission from a dream – fragmented, beautiful, deeply strange. Watching David Lynch's 1984 adaptation of Dune today, perhaps on a worn-out VHS tape pulled from the back of a shelf, evokes a specific kind of cinematic vertigo. It’s the feeling of witnessing something monumentally ambitious attempt to wrestle cosmic grandeur onto magnetic tape, succeeding in moments of startling vision while simultaneously collapsing under its own weight. This wasn't just another sci-fi flick lining the shelves of the local video store; it felt like an artifact from another dimension.

Whispers of Arrakis, Shouts of Exposition

Trying to condense Frank Herbert's sprawling, complex novel into a two-hour-plus film was always going to be a Herculean task. Herbert’s universe is dense with political intrigue, ecological themes, mystical prophecies, and intricate societal structures. Lynch, known more for his surreal explorations of the subconscious (Eraserhead, Blue Velvet), seemed an unlikely choice, yet producer Dino De Laurentiis, after the project passed through the hands of visionaries like Alejandro Jodorowsky and Ridley Scott, saw potential. The result is a film that often feels like Herbert's world – the decaying opulence of House Atreides, the industrial horror of House Harkonnen, the vast, unforgiving deserts of Arrakis – but struggles intensely to explain it.

The infamous voice-overs, often attributed to studio meddling demanding clarity, become almost a character in themselves. They frantically try to patch narrative holes and introduce concepts that the film barely has time to visualize. For many viewers back in the day, popping this tape into the VCR for the first time was an exercise in bewildered fascination. Who are these people? What is "spice"? Why does that baby look like that? It was confusing, yes, but also undeniably hypnotic. I distinctly remember renting this multiple times, not fully understanding it, but drawn back by its sheer, unyielding otherness.

A Troubled Vision, A Visual Feast

Despite the narrative compression, Lynch’s visual stamp is undeniable. This Dune is a triumph of production design and practical effects, embodying the tangible, lived-in feel that so much 80s fantasy and sci-fi possessed. The sets, designed by Anthony Masters, are baroque and often grotesque, reflecting the inner decay or industrial brutality of the ruling houses. The sandworms, while perhaps not as seamlessly integrated as modern CGI might allow, possess a terrifying physical presence – lumbering, ancient behemoths realised through miniature work and practical puppetry that still impresses. You feel the grit, the heat, the sheer scale of it all.

The production itself was notoriously difficult. Shot largely in Mexico's Churubusco Studios, the cast and crew battled intense heat, illness, and logistical nightmares. The budget ballooned to a reported $40 million (a huge sum for the time, maybe around $115 million today), fueled by Universal Pictures' hope for a Star Wars-level franchise starter. That dream, as we know, didn't quite pan out, with the film grossing only around $31 million domestically and receiving a critical drubbing. Lynch himself has famously distanced himself from the theatrical cut, frustrated by the studio's final control over editing, which excised vast swathes of material intended to flesh out the world and characters. One wonders what his original, reportedly much longer, cut might have looked like.

Faces in the Sandstorm

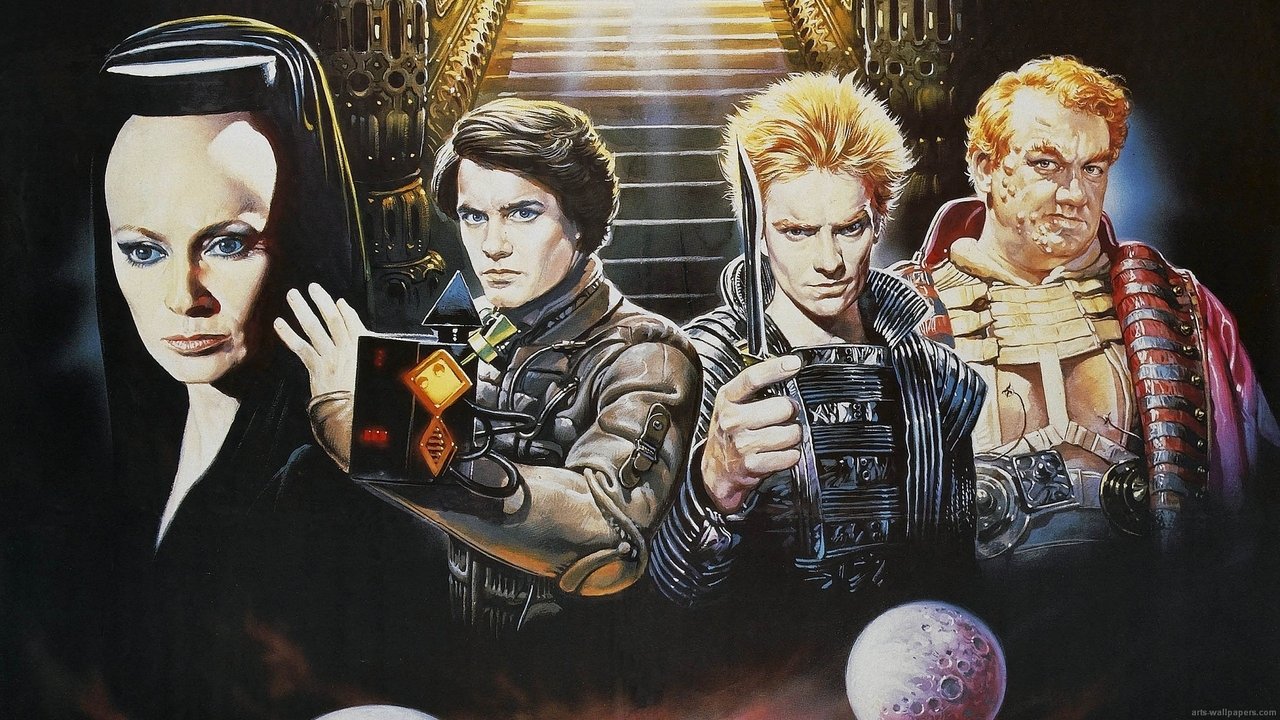

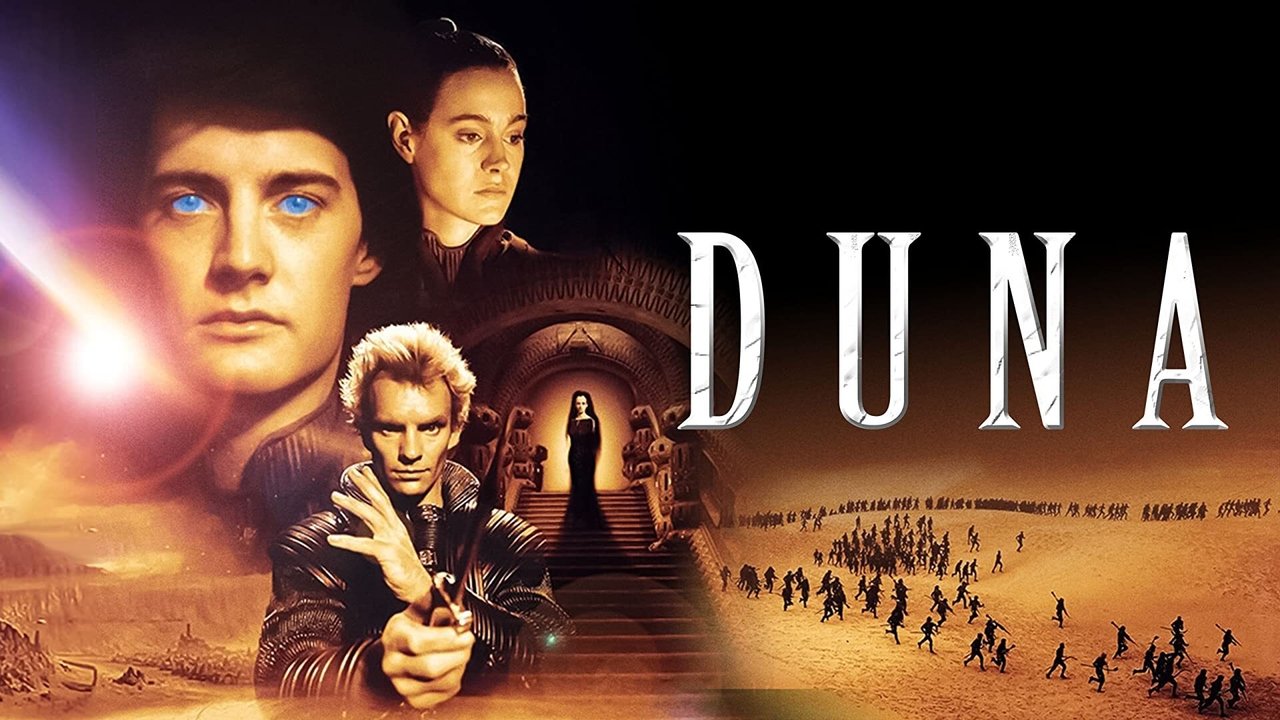

Amidst the visual splendor and narrative chaos, the cast does its best to anchor the proceedings. A young Kyle MacLachlan, in his film debut and beginning a long collaboration with Lynch, brings a compelling mix of youthful vulnerability and burgeoning messianic intensity to Paul Atreides. His internal struggles, often conveyed through those Lynchian close-ups, provide some of the film's most resonant moments. Francesca Annis lends regal gravity to Lady Jessica, embodying the arcane power and maternal concern of the Bene Gesserit.

Elsewhere, Jürgen Prochnow brings stoic nobility to Duke Leto Atreides, his fate casting a long shadow. Kenneth McMillan’s utterly repulsive Baron Harkonnen, floating and pustule-ridden, is a creation of pure nightmare fuel, unforgettable even if bordering on caricature. And then there's Sting, formerly of The Police, as the sneering Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen – a piece of stunt casting that feels very '80s, yet his wired, preening energy somehow fits the film's bizarre tapestry. Even smaller roles are filled with genre stalwarts like Max von Sydow, Patrick Stewart (with battle pug!), and Sean Young. Their presence adds a layer of gravitas, hinting at the richer character dynamics the film struggles to fully explore.

A Flawed Relic, An Enduring Curiosity

So, how do we regard Lynch's Dune now, decades removed from its troubled birth? It’s undeniably a mess – a beautiful, fascinating, often incomprehensible mess. Its narrative shortcomings are glaring, its pacing erratic, and its reliance on exposition clunky. Yet, it possesses a unique power. Its visual strangeness lingers. Its ambition, even in failure, is palpable. It’s a film born of a specific moment in blockbuster filmmaking, where practical effects wizards wrestled with epic source material, and auteur directors clashed with studio demands.

Watching it feels like unearthing a strange artifact, something imperfect but imbued with the personality and obsessions of its creator, however filtered. It doesn't fully capture Herbert's novel, nor does it perhaps entirely satisfy as a Lynch film, but it exists in a unique space between – a cult object cherished for its very weirdness and the ghost of what might have been. Doesn't its very existence, flawed as it is, speak volumes about the risks studios were once willing to take?

Rating: 6/10

The score reflects a film that is visually stunning and atmospherically potent, boasting unforgettable design and a certain audacious weirdness that commands attention. However, its profound narrative flaws, confusing exposition, and uneven pacing prevent it from reaching the heights of its ambition or source material. It's a captivating failure, essential viewing for Lynch completists and sci-fi historians, but a frustrating experience for those seeking a coherent adaptation.

Dune '84 remains a testament to cinematic ambition meeting harsh reality – a beautiful, bewildering desert mirage that continues to fascinate and divide audiences even now. What truly endures is not the story it tells, but the strange, haunting feeling it leaves behind.