There’s a certain kind of quiet that settles in after watching a film like Michelangelo Antonioni's Beyond the Clouds (1995). It’s not the silence of boredom, but the hushed resonance of questions left unanswered, of beauty observed but not quite grasped. Seeing that distinctive blue-and-white CIC Video clamshell case on the rental shelf back in the day might have felt like an invitation into a different world, far removed from the bombast often dominating the 90s blockbuster scene. This film, arriving late in the master's career, felt like a whisper, yet its echoes linger profoundly.

A Director Adrift

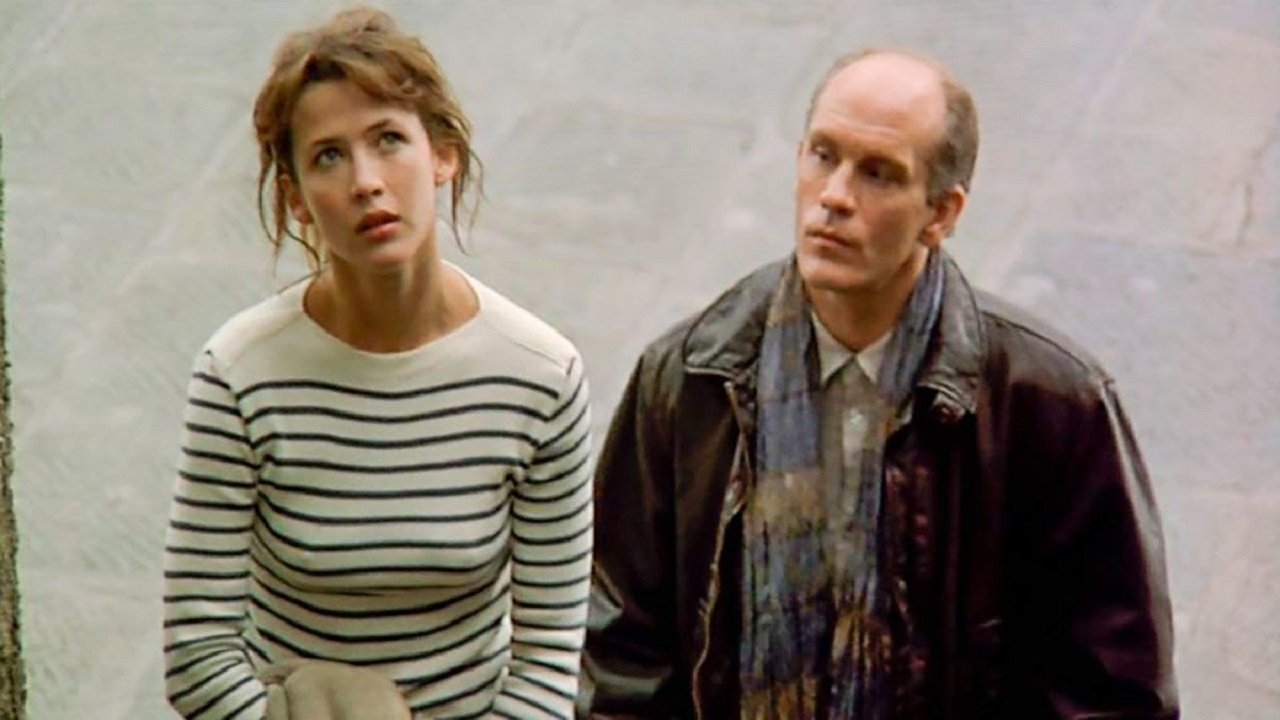

The film itself drifts, much like its framing narrator, a nameless Director played with a weary, searching intensity by John Malkovich. He wanders through Ferrara, Portofino, Aix-en-Provence, observing, listening, capturing fragments of stories – four distinct tales of love, desire, obsession, and the aching chasms that often lie between people. Malkovich, who had recently cemented his art-house credibility with films like The Sheltering Sky (1990), serves as our surrogate, but also as Antonioni's own stand-in, a lens through which these fleeting encounters are filtered. His presence anchors the vignettes, giving them a shared contemplative space, even as the stories themselves remain tantalizingly elliptical. What is he searching for? Perhaps the same thing Antonioni always sought: a glimpse into the elusive nature of human connection.

Portraits of Fleeting Desire

Each segment feels like a perfectly composed photograph, imbued with Antonioni's signature visual precision and deliberate pacing. We encounter Silvano (Kim Rossi Stuart) and Carmen (Inés Sastre) whose passionate encounter is instantly complicated by a shared past; the Director himself becoming briefly obsessed with a shop girl (a luminous Sophie Marceau) who reveals a shocking secret; Patricia (Fanny Ardant, radiating melancholy) navigating the complex currents of adultery and detachment with Carlo (Peter Weller); and Niccolò (Vincent Perez) falling for a young woman (the captivating Irène Jacob from Three Colors: Red (1994)) who plans to enter a convent.

These aren't stories resolved with neat bows. They are moments captured, emotions laid bare, often through glances, gestures, and the landscapes themselves. The dialogue, penned by Antonioni and his long-time collaborator Tonino Guerra, is spare, leaving much unsaid. It demands patience, an attunement to mood over plot mechanics. The performances feel grounded in this emotional ambiguity; Ardant, in particular, conveys worlds of unspoken feeling with just a look. We even get poignant late-career appearances from cinema legends Marcello Mastroianni and Jeanne Moreau, adding another layer of reflective weight.

A Testament to Vision, Born from Silence

Now, here’s where Beyond the Clouds becomes more than just another art film find in the video store aisles. This film exists as a near-miracle. Antonioni had suffered a debilitating stroke in 1985, leaving him severely paralyzed and largely unable to speak. For a director whose work depended so much on nuanced visual language and precise framing, it seemed an insurmountable obstacle. Yet, the desire to create burned bright. The solution came in the form of fellow auteur Wim Wenders (Paris, Texas (1984), Wings of Desire (1987)).

Wenders essentially acted as Antonioni's on-set facilitator, his bridge to the crew. Antonioni, communicating through gestures, drawings, and with the crucial help of his wife Enrica Fico Antonioni interpreting his wishes, would outline his vision for the vignettes. Wenders, a devoted admirer, helped translate this vision, directing the framing segments with Malkovich himself, ensuring the project Antonioni had nurtured from his own book of short stories, That Bowling Alley on the Tiber, could be realized. Knowing this backstory transforms the viewing experience. Malkovich's searching Director isn't just a narrative device; he becomes a poignant reflection of Antonioni himself, still observing, still seeking truth and beauty, even when robbed of his primary means of expression. It reportedly took considerable effort to secure the financing, with Wenders' name likely proving instrumental – a testament to artistic solidarity.

Atmosphere Over Action

Visually, the film is often breathtaking. The cinematography by Alfio Contini (for Antonioni's segments) captures the unique light and texture of Italy and France, while Robby Müller lens Wenders’ framing narrative with his own distinct eye. Of course, watching this on a fuzzy CRT via a well-loved VHS tape might have muted some of the subtleties, perhaps softening the edges of its carefully composed frames. Compared to the kinetic energy pulsing through so many 80s and 90s favourites, Beyond the Clouds moves at a languid, dreamlike pace. It asks you to slow down, to observe, to feel the weight of the unspoken. It’s the kind of film that might have tested the patience of someone looking for easy answers or quick thrills, but offered immense rewards for those willing to meet it on its own terms.

Lingering Impressions

Does a film about the ephemeral nature of connection, the gap between seeing and understanding, still hold power? I think so. Perhaps even more in our hyper-connected yet often isolating world. Antonioni's work consistently probed the difficulties of truly knowing another person, and Beyond the Clouds feels like a distillation of that lifelong inquiry. It doesn't offer conclusions, but rather leaves you with resonant images and a feeling – a sense of shared human longing that transcends language and time. Encountering it felt less like watching a movie and more like stepping into a series of profound, albeit fleeting, moments. What stays with you most profoundly after the screen goes dark? Isn't that often the mark of a truly memorable film?

Rating: 8/10

Beyond the Clouds is undeniably an art film, demanding a certain mood and patience. Its narrative fragmentation and emotional distance won't appeal to everyone. However, the sheer visual beauty, the haunting performances, and, above all, the astonishing story of its creation – a testament to Michelangelo Antonioni's indomitable artistic spirit facilitated by Wim Wenders’ selfless support – make it a unique and deeply moving piece of 90s cinema. It’s a film that embodies its title, reaching for something beautiful and intangible, just beyond the grasp of easy explanation, leaving you contemplating the mysteries of the human heart long after the tape finished rewinding.