It begins not with grand pronouncements, but with a quiet, devastating humiliation. A Polish hairdresser, Karol Karol, finds himself utterly adrift in Paris, his marriage annulled by his French wife, Dominique, for a reason both intimate and symbolic: impotence. Stripped of his passport, his money, his dignity, he’s left with nothing. This stark, almost bleak opening sets the stage for Krzysztof Kieślowski's 1994 film Three Colors: White (Polish: Trzy kolory: Biały), the middle, and perhaps most deceptively complex, entry in his acclaimed trilogy exploring the ideals of the French flag: Liberty, Equality, Fraternity. But how does one explore 'Equality' (Égalité) through such profound imbalance? That question hangs heavy in the air, long after the VCR whirs to a stop.

From Parisian Gutters to Polish Ambition

Unlike the ethereal blues of its predecessor (Three Colors: Blue, 1993), White grounds itself in a grittier reality, shifting dramatically from the indifferent grey elegance of Paris to the chaotic, muddy, yet strangely vibrant energy of post-communist Warsaw. Smuggled back into his homeland inside a suitcase (a darkly comic sequence in itself), Karol, played with extraordinary range by Zbigniew Zamachowski, begins a relentless climb back. This isn't just about regaining lost fortune; it's about reclaiming power, about achieving a skewed form of 'equality' with the woman who discarded him. Zamachowski is the heart of the film; his Karol is pathetic, resourceful, endearing, and ruthless, often all at once. His face, initially etched with bewildered hurt, slowly hardens with calculation. You see the gears turning, the wounded pride festering into a meticulously planned revenge. It’s a performance built on subtle shifts, from the hangdog slump of his shoulders in Paris to the determined stride he adopts back on Polish soil. Kieślowski, working closely again with co-writer Krzysztof Piesiewicz (his partner on the monumental Dekalog), seems less interested in literal equality and more fascinated by the messy, often cruel, human drive to level the playing field, even if it means tilting it violently in the other direction.

A Different Shade of Kieślowski

For those familiar with Kieślowski’s more overtly philosophical or melancholic works, White often feels like an outlier. It possesses a vein of dark, almost absurdist humor that bubbles beneath the surface. Karol’s schemes, his encounters with shady entrepreneurs, his unlikely friendship with the gentle, melancholic Mikołaj (a warm performance by Janusz Gajos, a titan of Polish cinema) – these moments offer glimmers of levity amidst the underlying desperation. Reportedly, Kieślowski himself referred to it as an "anti-comedy," finding humor in the tragic and the awkward corners of human experience. It’s a testament to his directorial control, aided by Zbigniew Preisner's evocative score, that the film navigates these tonal shifts without losing its footing. The visual contrast is striking too; the cold, impersonal feel of Paris gives way to a Poland grappling with newfound capitalism, a landscape of opportunity and opportunism, captured with a less stylized, more immediate feel than Blue or the later Red. Trivia buffs might appreciate knowing that much of the film was shot on location in a Warsaw visibly undergoing rapid transformation, adding a layer of documentary realism to Karol's journey of reinvention.

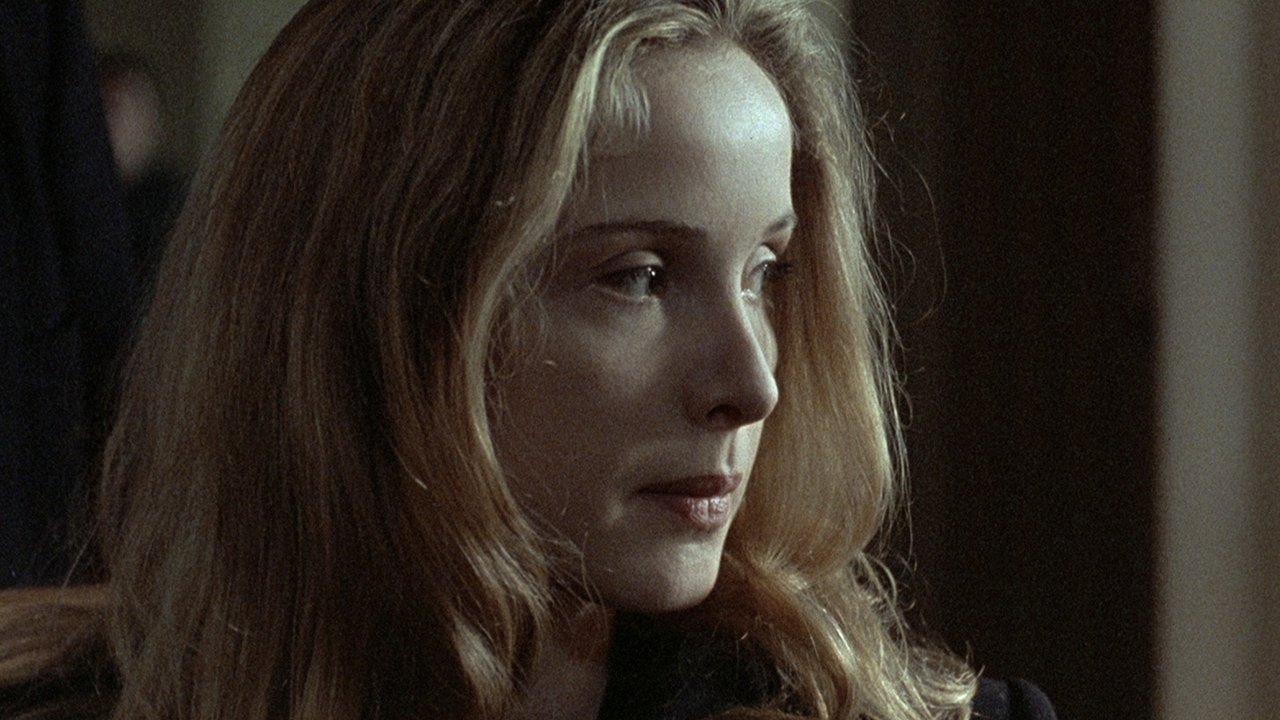

The Ghost of Dominique

While Karol dominates the narrative, the presence of Dominique, played with icy conviction by Julie Delpy (known to many from Richard Linklater's Before trilogy), looms large. Her appearances are relatively brief after the opening act, but her impact resonates throughout. She is the catalyst, the object of both Karol's lingering affection and his calculated vengeance. Delpy embodies a certain kind of unattainable French sophistication that initially crushes Karol, making his eventual turning of the tables all the more complex. Is his elaborate plot purely revenge, or is it a twisted attempt to force her to finally see him, to acknowledge his existence on truly equal terms, however destructive the method? Kieślowski leaves this deliberately ambiguous. The brief, almost hidden crossover appearances by characters from Blue and Red (notably in a courtroom scene) subtly reinforce the trilogy's interconnectedness, reminding us that these individual struggles are part of a larger human tapestry.

Achieving Equality, Losing Connection?

White is a fascinating puzzle. It takes the noble ideal of 'Equality' and examines it through the distorted lens of personal grievance and economic disparity. Karol achieves a form of parity, perhaps even superiority, in material terms, but what is the human cost? Does his meticulously crafted plan bring him satisfaction, or does it simply create a different kind of void? The film forces us to consider what equality truly means – is it merely about balancing the scales of power and wealth, or is there a deeper, more elusive emotional parity that Karol ultimately seeks, and perhaps tragically misunderstands? It’s a question that lingers, particularly in the film’s haunting final moments.

Final Reflection

Three Colors: White might be the most debated film in Kieślowski's trilogy, sometimes seen as lighter or less profound than its siblings. Yet, its blend of dark comedy, sharp social observation, and poignant character study offers a unique and resonant experience. Zamachowski's performance is a masterclass in transformation, carrying the film's emotional weight with incredible nuance. While perhaps lacking the sheer visual poetry of Blue or the intricate philosophical weave of Red, White possesses a raw, earthy energy and a provocative, cynical intelligence all its own. Finding this on VHS, perhaps nestled between more conventional dramas in the video store's 'World Cinema' section, felt like uncovering a different kind of cinematic gem – one that used irony and uncomfortable truths to explore a grand ideal.

Rating: 8.5/10

Justification: The score reflects the film's compelling central performance, its intelligent and unconventional exploration of the 'Equality' theme, Kieślowski's assured direction navigating tricky tonal shifts, and its unique place within a landmark trilogy. While perhaps not reaching the transcendent heights of Blue or Red for some viewers, its blend of dark humor, pathos, and sharp social commentary makes it a powerful and memorable work, elevated significantly by Zamachowski's tour-de-force acting.

Lingering thought: Can true equality ever be achieved through acts born of resentment, or does the pursuit itself inevitably create new forms of imbalance? White doesn't offer easy answers, leaving you to ponder Karol's ambiguous victory long after the screen fades to black.