Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle

It starts with the voice. That slow, deliberate, almost impossibly weary drawl that Jennifer Jason Leigh conjures for Dorothy Parker. It hangs in the air like cigarette smoke in a dimly lit bar, laden with wit that cuts like glass and a sorrow that feels bottomless. Watching Alan Rudolph’s Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle (1994) again, decades after first encountering it on a worn VHS tape probably tucked away in the ‘Drama’ section, it’s that voice – and the wounded spirit behind it – that immediately pulls you back into its intoxicating, melancholic world. This isn't your typical breezy 90s flick; it's something denser, sadder, and ultimately, more resonant.

Ghosts at the Round Table

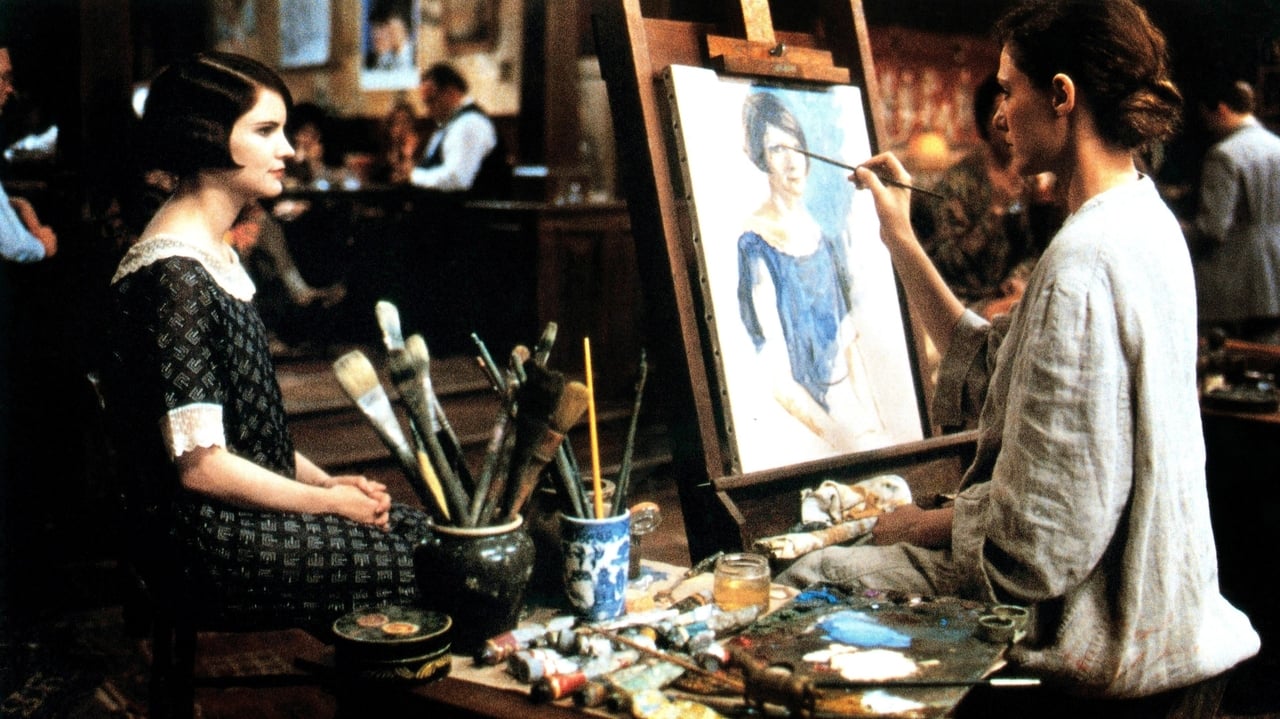

The film ostensibly chronicles the life of Dorothy Parker, celebrated poet, critic, and queen bee of the Algonquin Round Table – that legendary lunchtime gathering of New York's sharpest wits in the 1920s. We see the flashing repartee, the competitive wordplay, the rivers of bootleg gin. Alan Rudolph, working from a script he co-wrote with Randy Sue Coburn, doesn't just present these scenes; he immerses us in them. Borrowing a page from his mentor and the film's producer, the great Robert Altman (think Nashville or Short Cuts), Rudolph employs overlapping dialogue, restless camera movements, and a hazy, sepia-toned aesthetic that feels less like a historical recreation and more like a half-remembered dream, or perhaps a drunken reverie. It’s a bold choice, capturing the chaos and energy but also the inherent loneliness swimming beneath the surface of all that forced conviviality. Finding this on VHS back in the day, nestled perhaps between more straightforward biopics, felt like unearthing something special, something that demanded more attention than your average rental.

The Weight of Wit

At the heart of it all is Jennifer Jason Leigh. Her portrayal of Parker is nothing short of extraordinary, a feat of mimicry that transcends imitation to become a fully inhabited character study. It's reported Leigh listened extensively to the scant existing recordings of Parker's voice, capturing that unique, languid cadence. But it’s more than the voice. Leigh embodies Parker’s physical fragility, the slight frame housing a ferocious intellect and an even more ferocious capacity for self-destruction. She shows us the devastating cost of being the sharpest tongue in the room – the isolation, the insecurity, the desperate longing for genuine connection masked by a relentless barrage of bon mots. We see the wit as both a shield and a weapon, one she turns as often on herself as on others. Does her constant performance of "Dorothy Parker" ultimately consume the woman underneath? It’s a question the film allows to linger, unresolved and haunting.

A Circle of Familiar Faces

Surrounding Leigh is an impressive ensemble cast tasked with portraying literary giants, a challenge Rudolph handles with dexterity. Campbell Scott is wonderfully sympathetic as Robert Benchley, Parker's closest friend and perhaps the film’s quiet conscience. His gentle humor and unspoken affection provide a crucial anchor amidst the often brittle exchanges. Matthew Broderick, stepping away from his more boyish roles, plays Charles MacArthur, Parker’s charming but unreliable second husband, capturing the allure and the ultimate disappointment. The large cast, featuring actors like Peter Gallagher as Alan Campbell, Jennifer Beals as Gertrude Benchley, and Wallace Shawn as Horace Ross, drift in and out, contributing to the Altmanesque tapestry of lives intersecting, often carelessly, around Parker's orbit. Filming these intricate group scenes, especially those set at the Algonquin Hotel (though primarily shot in Montreal to recreate 1920s New York on a budget), must have been a logistical dance, choreographing the overlapping talk and subtle glances that define the Round Table's dynamic.

Beyond the Bon Mots

While the film celebrates the dazzling wordplay associated with Parker and her circle ("What is it about my liver that excites your spleen?"), it never shies away from the darkness. Parker's struggles with alcohol, her tumultuous relationships, and her multiple suicide attempts are depicted frankly, often interwoven with recitations of her own poignant, deceptively simple poetry rendered in stark black and white sequences. These moments provide glimpses into the raw vulnerability beneath the polished, cynical facade. Rudolph isn't interested in hagiography; he presents a complex, often contradictory figure, brilliant and self-destructive in equal measure. The film cost around $6 million to make, a modest sum even then, and while critically acclaimed (Leigh garnered numerous awards nominations), it wasn't a mainstream hit. It remained more of a connoisseur's piece, something film lovers sought out, perhaps sharing a treasured tape among friends.

Lingering Echoes

Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle isn't a film you watch for easy answers or comforting resolutions. It's an immersion into a specific time, place, and sensibility, filtered through the bruised consciousness of its central figure. It explores the complex relationship between creativity, fame, wit, and personal happiness, suggesting that sometimes the brightest sparks burn out the fastest, leaving behind a legacy etched in brilliance and regret. Does the relentless pursuit of being clever ultimately poison the possibility of contentment? The film offers no easy verdict, leaving the viewer to ponder Parker's enigmatic life long after the credits fade.

Rating: 8.5/10

This score reflects the film's artistic ambition, Jennifer Jason Leigh's powerhouse central performance, Alan Rudolph's evocative direction, and its unflinching look at a fascinating, flawed historical figure. It’s a demanding film, perhaps, its deliberately paced, dialogue-heavy nature not for everyone, especially those expecting a conventional biopic. But for viewers willing to sink into its smoky atmosphere and complex character study, it offers rich rewards. It stands as a high point of 90s independent filmmaking, a reminder of a time when challenging, adult dramas could still find their way onto those cherished video store shelves.