It starts with the sound, doesn't it? The tired tinkle of lounge piano keys echoing in a half-empty room, a melody worn smooth like river stones. That's the immediate pull of The Fabulous Baker Boys, a film that settles into your consciousness not with a bang, but with a melancholic chord that resonates long after the credits roll. Released in 1989, it felt different even then, a grown-up movie nestled amongst the louder spectacles on the video store shelves. It wasn't about heroes or villains in the conventional sense, but about the quiet desperation and flickering hopes of people trying to make a living, and maybe, just maybe, make a life.

Two Brothers, One Tired Act

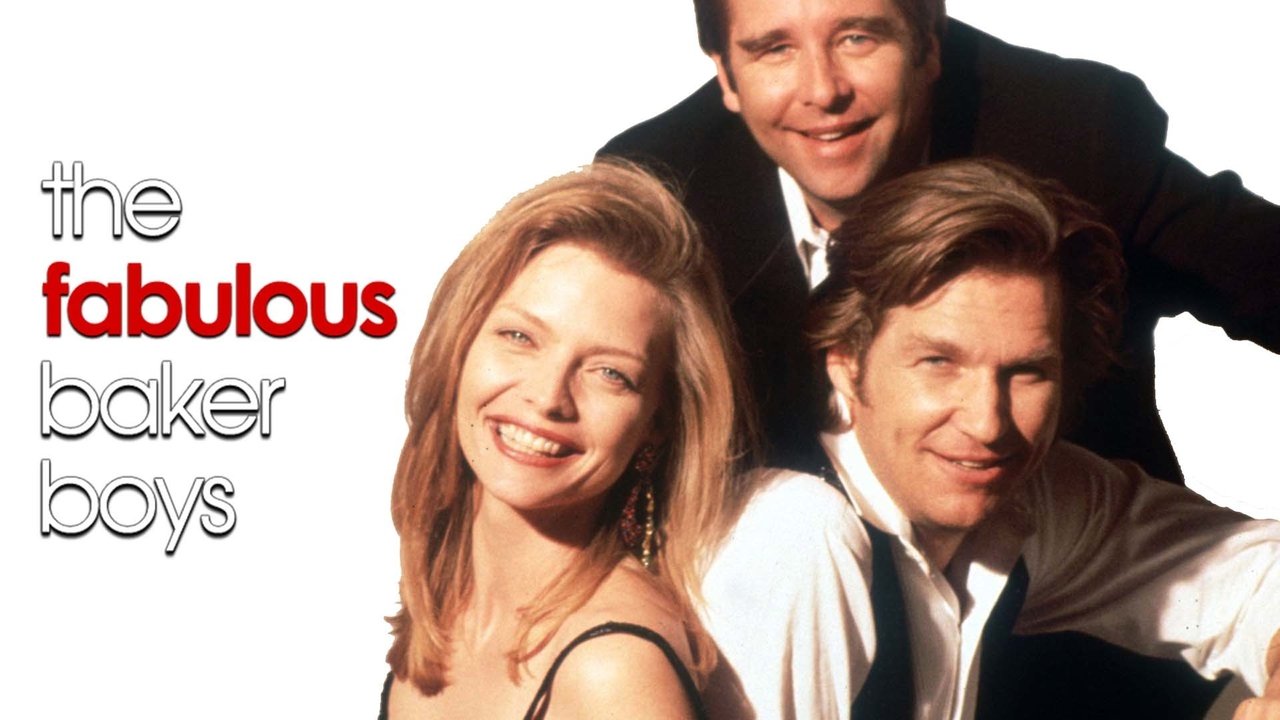

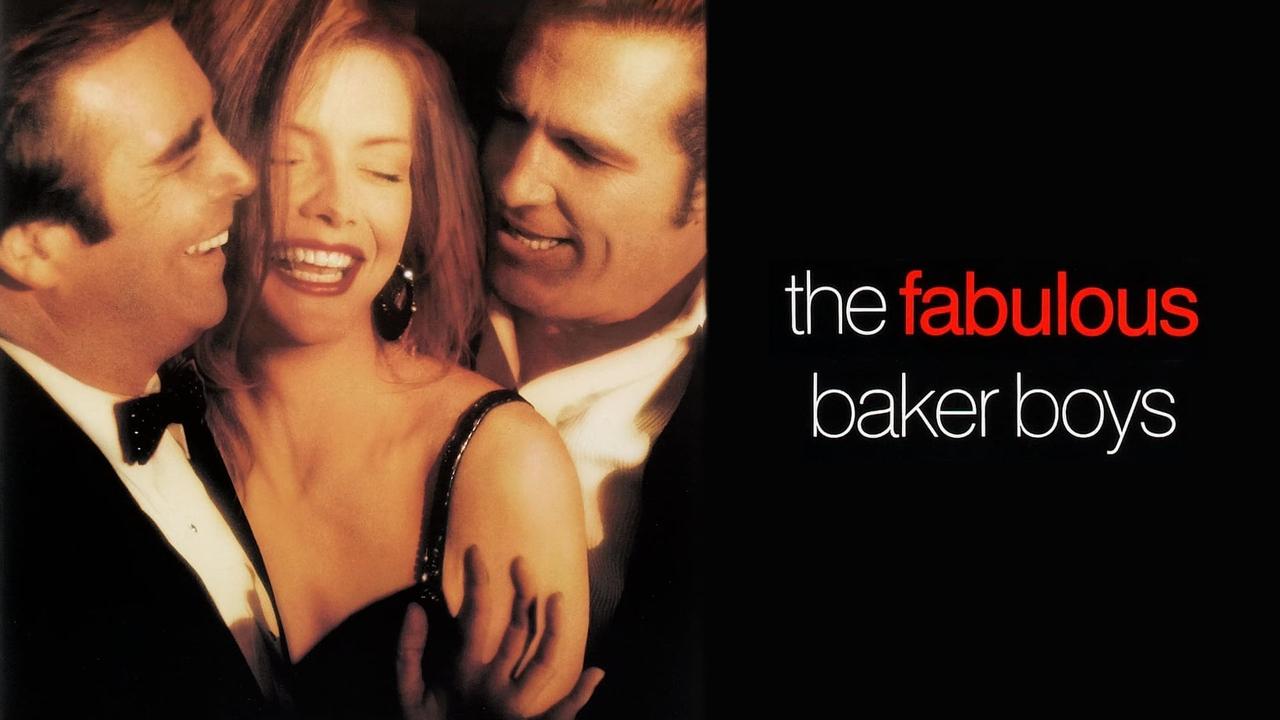

At the heart of the film are Jack and Frank Baker, played with an almost unnerving authenticity by real-life brothers Jeff Bridges and Beau Bridges. Their dynamic is the film's bruised, beating heart. Jeff’s Jack is the smouldering talent, the gifted pianist whose cynicism hangs heavier than the smoke in the dimly lit bars they play. He’s coasting, maybe even drowning, pouring his artistry into predictable standards for audiences who barely listen. You see the frustration etched on his face, the subtle ways he telegraphs his boredom and resentment, a performance built on nuance rather than broad strokes. It’s a masterful portrayal of stifled potential.

Contrast him with Beau’s Frank, the pragmatic older brother, the manager, the one keeping the books and booking the gigs. Frank is the anchor, perhaps, but also the weight. He’s married, has kids, and sees the Baker Boys act purely as a job, a way to pay the bills. Beau Bridges resists making Frank a simple foil; there's a genuine warmth there, a sense of responsibility that borders on the suffocating, and a deep, perhaps unacknowledged, reliance on Jack's talent. The fact that they are brothers lends an immediate, unshakeable foundation to their complex relationship on screen. Writer-director Steve Kloves, in his remarkably assured directorial debut (before he went on to adapt most of the Harry Potter series), actually wrote the parts specifically with them in mind, sensing that innate connection would translate powerfully.

Enter the Spark

The comfortable, if stagnant, routine is shattered by the arrival of Susie Diamond. And what an arrival. Michelle Pfeiffer, in a career-defining, Oscar-nominated performance, doesn't just join the act; she electrifies it. Susie is a former escort trying to break into singing, possessing a raw, untrained charisma and a voice that cuts through the stale lounge air. Pfeiffer embodies Susie's contradictions perfectly – the tough, seen-it-all exterior protecting a core of vulnerability and ambition. She's nobody's fool, least of all Jack's, and their verbal sparring crackles with an intelligence and chemistry that feels utterly real.

It’s worth remembering that Pfeiffer did all her own singing, a fact that adds immensely to the authenticity. Who can forget the scene where she drapes herself across Jack’s piano to deliver a rendition of "Makin' Whoopee" that is simultaneously sultry, playful, and deeply knowing? It’s an iconic moment, reportedly rehearsed meticulously, capturing the exact turning point where the dynamic shifts irrevocably. Kloves apparently considered a number of high-profile actresses for the role, including Madonna and Debra Winger, but it's hard to imagine anyone else capturing Susie's specific blend of weary glamour and guarded hope quite like Pfeiffer.

Atmosphere is Everything

Beyond the performances, Kloves and cinematographer Michael Ballhaus (known for his work with Scorsese, including Goodfellas the following year) conjure a specific, palpable mood. The film lives in those late-night hours, in the blue haze of cigarette smoke, the reflections in rain-slicked Seattle streets (where much of it was filmed), and the slightly worn elegance of hotel lounges. It feels like the end of an era, not just for the Baker Boys' act, but perhaps for a certain kind of intimate, small-scale entertainment. The Oscar-nominated score by jazz legend Dave Grusin is inseparable from this atmosphere, weaving jazz standards seamlessly with original compositions that underscore the characters' emotional states – the longing, the frustration, the fleeting moments of connection.

More Than Just a Performance Piece

While the acting rightfully gets the spotlight, The Fabulous Baker Boys offers more. It asks quiet questions about compromise: How much of your soul do you sell to make a living? When does pragmatism become artistic death? Jack's talent is undeniable, yet he squanders it on autopilot. Susie's arrival forces him, and Frank, to confront the rut they're in. The film doesn't offer easy answers. It understands the complexities of sibling bonds – the love, the resentment, the deep-seated patterns that are hard to break.

The film was made for a relatively modest $11.5 million (around $28 million today) and while it wasn't a box office smash, earning about $18.4 million domestically, its critical reception was warm, particularly for the performances and Kloves' sensitive direction. It garnered four Academy Award nominations (Pfeiffer for Actress, Ballhaus for Cinematography, Grusin for Score, and William Steinkamp for Editing), cementing its status as a standout adult drama of the period. It’s a film built on character and atmosphere, a slow burn that trusts its audience to appreciate the subtle shifts in emotion and unspoken tensions. I recall renting this on VHS, expecting maybe a lighter romance, and being struck by its depth and bittersweet quality – it felt sophisticated, mature, and stayed with me.

Final Chord

The Fabulous Baker Boys remains a potent character study, anchored by three exceptional performances that feel lived-in and true. It captures a specific mood and time, exploring themes of artistic compromise, sibling relationships, and the courage it takes to change course, even late in the game. It’s a film that rewards patience, inviting you to simply sit with these characters in their smoky, melancholic world.

Rating: 9/10

Justification: The performances are virtually flawless, particularly Pfeiffer's star-making turn and the authentic dynamic between the Bridges brothers. Kloves' writing and direction are remarkably nuanced and assured for a debut, creating a palpable atmosphere perfectly complemented by Ballhaus' cinematography and Grusin's score. It tackles mature themes with grace and avoids easy sentimentality. A near-perfect example of character-driven drama from the era.