It starts with a wrong turn, a moment of vulnerability under the vast, indifferent sprawl of Los Angeles. That single terrifying incident ripples outwards, connecting disparate lives in Lawrence Kasdan’s ambitious ensemble drama, Grand Canyon (1991). Watching it again, perhaps on a less-than-perfect copy than my original rental store find back in the day, the film feels less like a simple narrative and more like a tapestry woven from the anxieties and unexpected connections of modern urban life, a feeling that hasn't entirely faded in the intervening decades. Co-written with his wife, Meg Kasdan, reportedly inspired by a similar nerve-wracking event she experienced, the film carries an intimate, questioning quality beneath its Hollywood sheen.

### Intersections of Chance

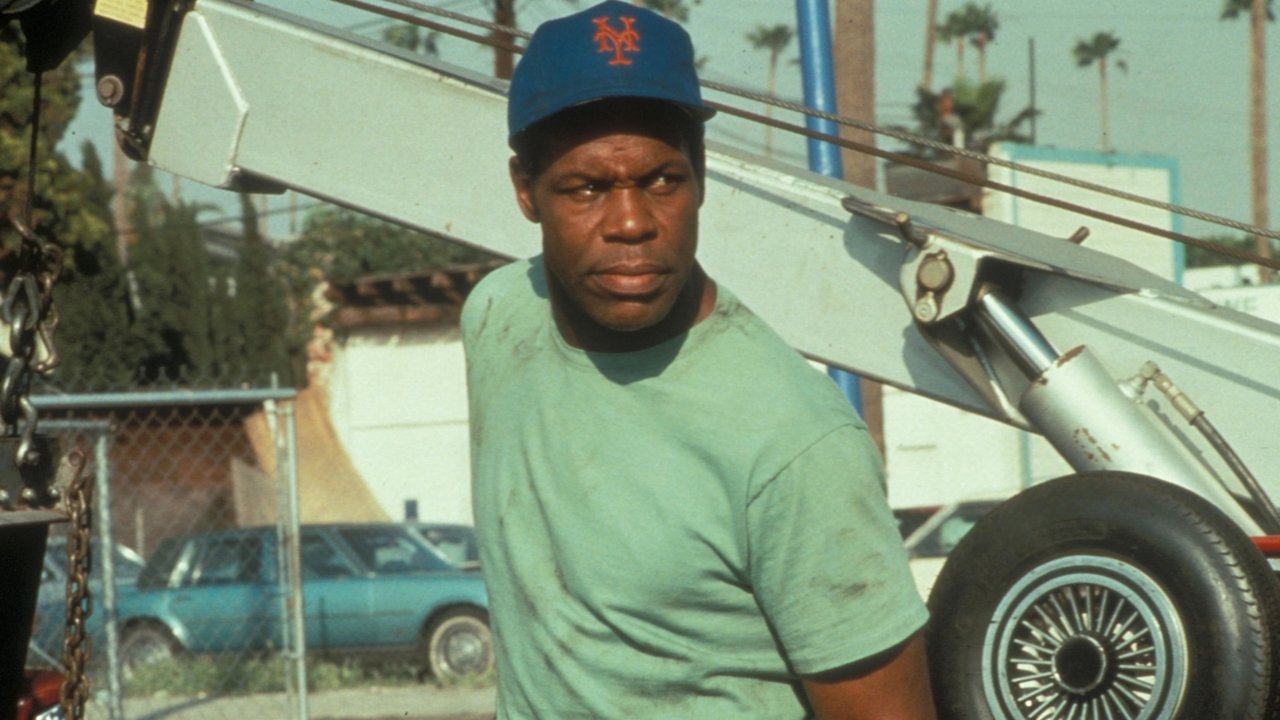

At its heart, Grand Canyon explores how seemingly random events can forge profound, if sometimes fragile, bonds. Mack (Kevin Kline, bringing his trademark blend of intelligence and subtle bewilderment), an immigration lawyer, finds himself stranded in a dangerous neighborhood after a Lakers game. His rescue by Simon (Danny Glover, radiating weary decency), a tow truck driver who defuses the situation with quiet authority, becomes the catalyst. Their burgeoning friendship, crossing racial and class lines, feels both tentative and essential. Kasdan, who previously explored group dynamics in The Big Chill (1983), broadens his scope here, examining the fault lines running through a society struggling with alienation, violence, and a search for meaning.

The film isn't just about Mack and Simon. It branches out, touching the lives of Mack's wife, Claire (Mary McDonnell, capturing a poignant sense of mid-life yearning), who discovers an abandoned baby; Mack's friend Davis (Steve Martin, in a startlingly sharp turn), a producer of gratuitously violent action films who experiences his own traumatic wake-up call; Simon's sister (Alfre Woodard, grounded and pragmatic), dealing with her son's descent into gang culture; and Dee (Mary-Louise Parker, conveying raw vulnerability), Mack's secretary with whom he had a brief affair. Each thread explores a different facet of disconnection and the tentative grasp for something more substantial.

### Echoes in the Urban Landscape

What strikes me now is how keenly Grand Canyon captured the specific anxieties of its time – the palpable fear of urban decay, random violence, and social fragmentation simmering in early 90s America. Filmed before the Los Angeles riots of 1992 but released shortly thereafter, the movie gained an almost uncomfortable prescience. The scenes depicting street-level tension, the casual disregard for life portrayed in Davis's schlocky films (a role Steve Martin reportedly modeled partly on producer Joel Silver), and the characters' pervasive sense of unease felt incredibly current then, and elements sadly still resonate.

Lawrence Kasdan directs with a steady, observational hand, letting the city itself become a character. The cinematography contrasts the claustrophobic, often threatening, streets of LA with the eventual, breathtaking release of the titular canyon. James Newton Howard's score complements this, shifting from urban rhythms to soaring, almost spiritual cues. Kasdan trusts his actors, allowing moments of quiet reflection and nuanced interaction to carry the emotional weight. There’s a truthfulness in the performances – Kline’s discomfort navigating unfamiliar territory (both physically and emotionally), Glover’s profound stillness suggesting deep currents of experience, McDonnell’s desperate hope, and Martin’s shocking pivot from cynical showman to wounded man. It’s a reminder of how effective Martin could be when stepping outside his purely comedic persona.

### Retro Fun Facts Weaved In

- The film was a personal project for the Kasdans, taking years to develop after Meg Kasdan's unsettling real-life experience. This personal investment likely contributes to the film's sincere, questioning tone.

- Despite its serious themes and ensemble nature, Grand Canyon found critical favour, winning the prestigious Golden Bear for Best Film at the 42nd Berlin International Film Festival – quite an achievement for a mainstream American drama.

- While not a massive blockbuster (grossing around $40.9 million worldwide on a $21 million budget – roughly $86M and $44M today), its thoughtful exploration of contemporary issues struck a chord with audiences seeking something more substantial than typical Hollywood fare.

- The contrast between Davis's hyper-violent movie clips and the film's own more measured tone feels like a deliberate commentary by Kasdan, who himself had written for blockbusters like Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and The Empire Strikes Back (1980).

### The Canyon as Metaphor

Of course, the film culminates in the shared experience of the Grand Canyon itself. Is the metaphor a bit on the nose? Perhaps. The vastness, the perspective shift, the sense of something ancient and powerful dwarfing human concerns – it’s not subtle. Yet, there's an undeniable power in these closing scenes. Seeing these characters, buffeted by the chaos of their lives, stand together in awe offers a fragile, earned sense of hope. It suggests that connection, however improbable, and finding perspective, however fleeting, are possibilities worth striving for. Does it neatly solve all the complex issues raised? No, and perhaps that’s the point. The immensity of the canyon mirrors the immensity of the problems, but also the potential for wonder and connection within them.

What lingers after watching Grand Canyon today isn't necessarily a perfect resolution, but a feeling – a thoughtful melancholy mixed with a glimmer of optimism. It’s a film that asks big questions about how we live together, how chance shapes us, and whether we can bridge the gaps that divide us. In the sometimes-cynical landscape of early 90s cinema, its earnestness felt, and still feels, quite refreshing.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's intelligent script, deeply felt performances from its stellar ensemble cast, and Lawrence Kasdan's sensitive direction. It successfully captures a specific cultural moment while exploring universal themes of connection and anxiety. While the central metaphor might feel slightly overt to some, the film’s emotional honesty and the power of its individual character arcs make it a resonant and rewarding watch. It remains a thoughtful piece of filmmaking that encourages reflection long after the credits roll – a quality that always earns a respected place on my shelf, virtual or physical. What does that final gaze over the canyon truly signify for each character, and perhaps, for us?