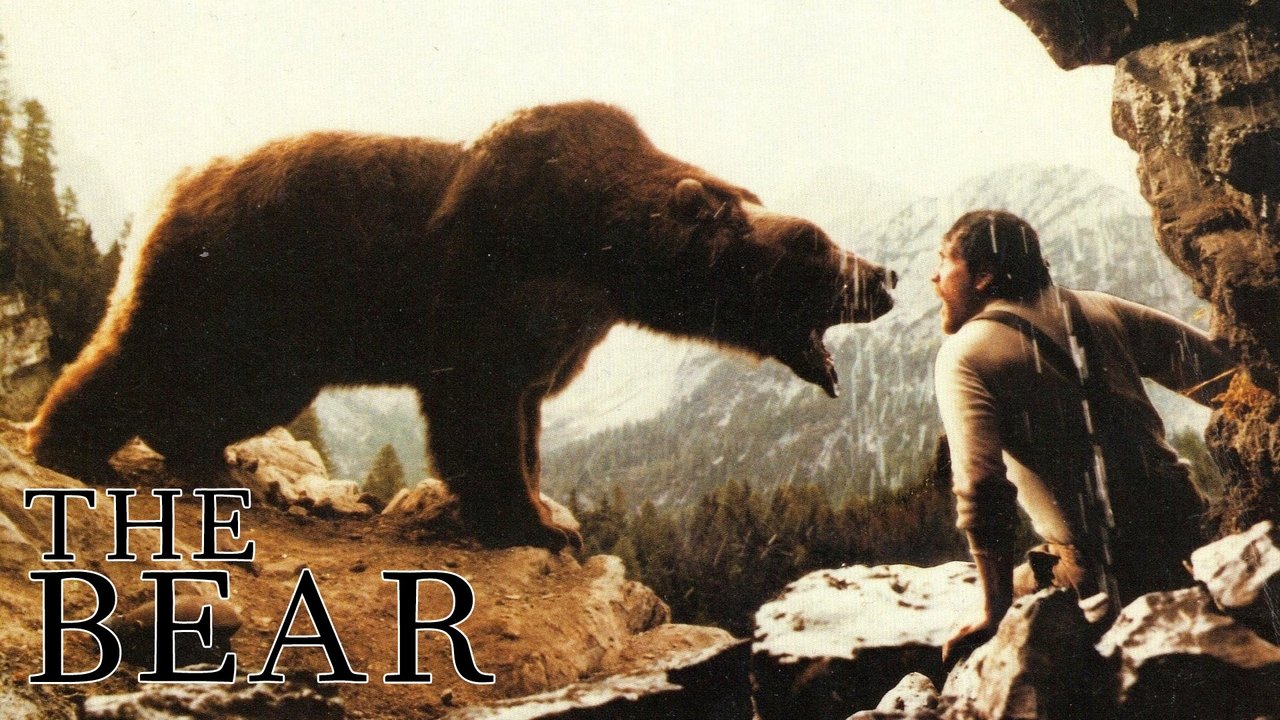

It’s hard to forget the first time you witnessed the world through the eyes of a grizzly. In 1988, Jean-Jacques Annaud delivered something utterly unique to cinemas and, shortly after, to our beloved VHS players: The Bear. This wasn't just another nature documentary; it was a full-blown narrative drama where the protagonists happened to have claws, fur, and communicated entirely without subtitles. For many of us watching on fuzzy CRT screens, it felt less like a movie and more like being dropped, heart-pounding, into the vast, untamed wilderness of 19th-century British Columbia.

### A Tale Told Without Words

The premise, drawn from James Oliver Curwood's 1916 novel The Grizzly King, is deceptively simple: an orphaned grizzly cub, clumsy and vulnerable, finds an unlikely protector in a massive adult male grizzly. Together, they navigate the perils of the wild, including the relentless pursuit by two human hunters. What elevates The Bear beyond a simple animal story is Annaud's audacious decision, along with screenwriter Gérard Brach (who also collaborated with Annaud on the prehistoric saga Quest for Fire in 1981), to tell this story almost entirely from the bears' perspective, with minimal human dialogue. It was a gamble that paid off spectacularly, forcing us to rely on visual storytelling, animal behaviour, and the sheer expressive power of its non-human stars.

The weight of the film rests squarely on the shoulders – quite literally – of its animal actors. The young cub, affectionately known as Youk on set (actually portrayed by several female cubs due to rapid growth rates), is heartbreakingly convincing as the lost innocent. But the undisputed star is the magnificent Kodiak bear known as Bart the Bear. Trained by the legendary Doug and Lynne Seus, Bart delivers a performance of staggering depth and presence. He conveys rage, curiosity, tenderness, and weariness with just a look or a shift in posture. This wasn't just animal wrangling; it felt like true acting. It’s no wonder Bart became a sought-after animal star, later appearing opposite Anthony Hopkins in The Edge (1997) and Brad Pitt in Legends of the Fall (1994). Seeing him command the screen here is truly something special.

### The Majesty and Danger of the Wild

Annaud, never one to shy away from a logistical nightmare, spent years preparing for this shoot. Filming primarily in the stunning, rugged landscapes of the Italian and Austrian Dolomites (a convincing stand-in for B.C.), the production faced immense challenges. Ensuring the safety of cast and crew while working with apex predators required meticulous planning and nerves of steel. Cages and discreet electric fences were often just out of frame. Yet, the result is footage that feels breathtakingly authentic. The cinematography captures both the idyllic beauty and the sudden, brutal danger of the natural world. You feel the damp earth, smell the pine needles, and sense the looming threat just beyond the treeline.

Remember watching those scenes where Youk stumbles through the forest, trying to mimic the big bear? Or the heart-stopping encounters with the hunters, led by a grimly determined Tchéky Karyo (who would soon become a familiar face in films like Nikita and GoldenEye)? These moments are crafted with incredible skill. The film even includes a controversial, dream-like sequence involving hallucinogenic mushrooms, a bizarre but memorable detour that certainly sparked conversations back in the day! It’s this commitment to showing, not telling, that earned the film an Academy Award nomination for Best Film Editing – a rare feat for a film of this nature, recognizing the immense task of weaving a compelling narrative from thousands of hours of animal footage.

### Retro Fun Facts & Lasting Paw Prints

The Bear wasn't cheap, costing somewhere around $24 million in 1988 dollars, a hefty sum for a film with virtually no dialogue and non-human leads. Yet, it struck a chord worldwide, becoming a surprise hit and grossing over $100 million globally (pulling in a respectable $31.7 million stateside). It proved audiences were hungry for different kinds of cinematic experiences.

One fascinating aspect was how Annaud and his team managed to elicit such specific actions and seemingly emotional responses from the bears. It involved infinite patience, understanding animal psychology, and cleverly using hidden trainers and lures. The famous scene where the adult bear shows mercy to a cornered hunter wasn't just movie magic; it was a carefully orchestrated sequence built around Bart's training and natural behaviours, profoundly reinforcing the film's underlying message about respect for life. The story goes that Annaud spent weeks simply observing bears in captivity before filming began, immersing himself in their world to better understand how to capture it on film.

While Tchéky Karyo and Jack Wallace represent the human intrusion into this world, their roles are secondary. They are forces of nature in their own right, driven by instinct and the harsh realities of survival in that era, but the film never lets us forget that the true emotional core lies with the bears.

### Final Thoughts

The Bear remains a unique cinematic achievement. It’s a film that transports you, engages your empathy in unexpected ways, and leaves you with a profound sense of awe for the natural world. It doesn't anthropomorphize the animals excessively; instead, it invites us to observe and understand them on their own terms. Watching it again now, decades after first sliding that tape into the VCR, its power hasn't diminished. It’s a thrilling, sometimes harrowing, but ultimately deeply moving journey.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's sheer ambition, the groundbreaking work with animal actors (especially Bart), the breathtaking cinematography, and its unique, dialogue-minimal storytelling approach that creates a powerful emotional impact. It’s a near-perfect execution of a concept that could easily have failed. It might move a little deliberately for some modern viewers, and the intensity is real, but its artistry is undeniable.

The Bear isn't just a nostalgic artifact; it’s a timeless reminder of the wild majesty that exists just beyond our doorstep, captured with a cinematic magic rarely seen before or since. A true gem from the wilderness of the video store era.