Some films wash over you. Others feel like being dragged face-down through gravel. Gaspar Noé’s 1991 gut-punch, Carne, belongs squarely in the latter category, a 40-minute descent into a world so bleak it leaves a permanent residue on your soul. Finding this on a worn VHS tape back in the day felt like discovering something illicit, something you maybe weren't supposed to see – a feeling Noé likely intended. This wasn't your standard video store fare; this was a raw nerve exposed on celluloid.

### The Stench of Reality

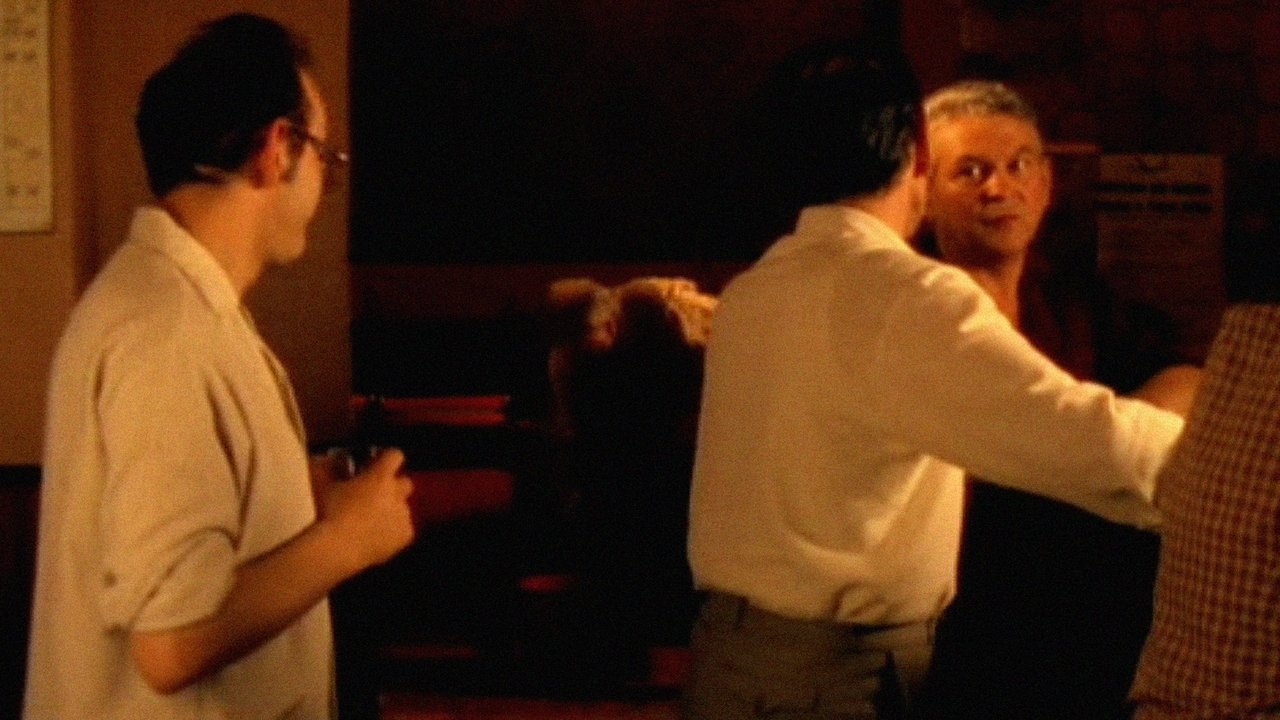

From its opening moments within the grimy confines of a horse butcher shop, Carne establishes an atmosphere of oppressive dread. There's no glamour here, no cinematic sheen. We're thrust into the world of 'Le Boucher' (The Butcher), played with terrifying, simmering intensity by the late, great Philippe Nahon. His face, a landscape of weariness and barely suppressed rage, becomes the film's desolate focal point. Noé, even this early in his career, demonstrates a chilling mastery of mood, using stark, static compositions and the unsettling sounds of the abattoir – the squelch of meat, the harsh clang of tools – to create a visceral sense of discomfort long before the narrative truly darkens. The colour palette itself feels bruised, favouring sickly yellows and institutional blues that amplify the feeling of decay.

### A Provocation, Not an Invitation

Let's be blunt: Carne is confrontational cinema. It delves into themes of incestuous desire, violence, and social alienation with an unflinching gaze that defined what would later be termed the 'New French Extremity'. (Spoiler Alert for specific plot points ahead) The plot centers on The Butcher's obsessive, unhealthy love for his mute daughter, Cécile (Blandine Lenoir), and the brutal act of misplaced vengeance he commits when he believes she's been assaulted. The violence, when it erupts, is sudden, clumsy, and sickeningly real – far removed from the stylized action prevalent in the era. Noé forces us to confront the ugliness, refusing to look away or offer easy catharsis. It’s a viewing experience that challenges your limits. Did finding this tucked away on a shelf, maybe with a plain, hand-written label, ever prepare you for this level of raw transgression?

### The Birth of a Style

Even in this relatively early work (partly self-funded by Noé after working on commercials and shorts), the director's notorious signatures are present. The abrupt, percussive editing, the jarring use of intertitles flashing warnings or blunt statements ("WARNING: This film contains scenes that may shock"), the methodical, almost detached observation of horrific events – it's all here. There's a palpable sense of watching human wreckage unfold under a microscope. The film’s medium length (around 40 minutes) works perfectly, concentrating its venom into a potent, unforgettable dose. It’s said Noé struggled to get funding, which perhaps contributed to the film's raw, stripped-down aesthetic – a prime example of creative necessity birthing a unique style. Its subsequent win of the Critic's Week prize at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival certainly raised eyebrows and announced Noé as a fearless new voice, even if distributors were hesitant.

### The Butcher's Shadow

Philippe Nahon’s portrayal of The Butcher is simply unforgettable. It’s a performance devoid of vanity, embodying a man pushed to the edge by loneliness, societal neglect, and his own twisted psyche. His internal monologue, delivered in a gravelly voiceover, provides a disturbing window into his nihilistic worldview. It’s a role that would define much of Nahon’s later career, particularly when he reprised the character in Noé’s feature-length follow-up, I Stand Alone (1998), which picks up The Butcher's story after the events of Carne. Watching Carne now feels like witnessing the grim origin story not just of a character, but of a specific, confrontational strain of filmmaking. It’s fascinating to learn that Noé and Nahon developed a close working relationship, with Nahon becoming a recurring figure in Noé's challenging cinematic universe, appearing later in Irreversible (2002).

Carne isn't 'enjoyable' in the conventional sense. It’s brutal, disturbing, and deeply pessimistic. Yet, for those interested in the extremes of cinema, or the early work of one of modern film's most provocative auteurs, it remains essential viewing. Watching it on VHS, perhaps late at night with the volume low, felt like handling something dangerous, a grainy transmission from the darkest corners of the human condition. It’s a film that doesn’t just depict ugliness; it makes you feel it in your bones.

---

Rating: 8/10

Justification: While undeniably difficult and repellent for many viewers, Carne is a masterclass in atmospheric dread and raw, confrontational filmmaking. Noé's vision is singular and fiercely executed, Nahon's performance is iconic, and its power to shock and disturb remains undiminished. It’s a significant early work that laid the groundwork for I Stand Alone and cemented Noé's reputation. The rating reflects its artistic merit and impact within its niche, acknowledging its extreme nature prevents a universal recommendation.

Final Thought: Decades later, the visceral chill of Carne lingers – a potent reminder that sometimes the most impactful films are the ones that dare to stare directly into the abyss. It’s a foundational text of extremity, uncompromising and unforgettable.