Some films arrive like a pleasant postcard from the past; others land like a philosophical hand grenade rolled gently across the floor, fuse sputtering. Marco Ferreri’s The Flesh (1991), or La Carne as it’s known in its native Italian, definitely belongs in the latter category. It's the kind of movie that, once encountered on a grainy VHS rented perhaps out of morbid curiosity from the 'World Cinema' shelf, doesn't easily fade. What does it mean to truly possess another person, and where does consuming love tip over into something far more literal and terrifying?

An Unsettling Seaside Serenade

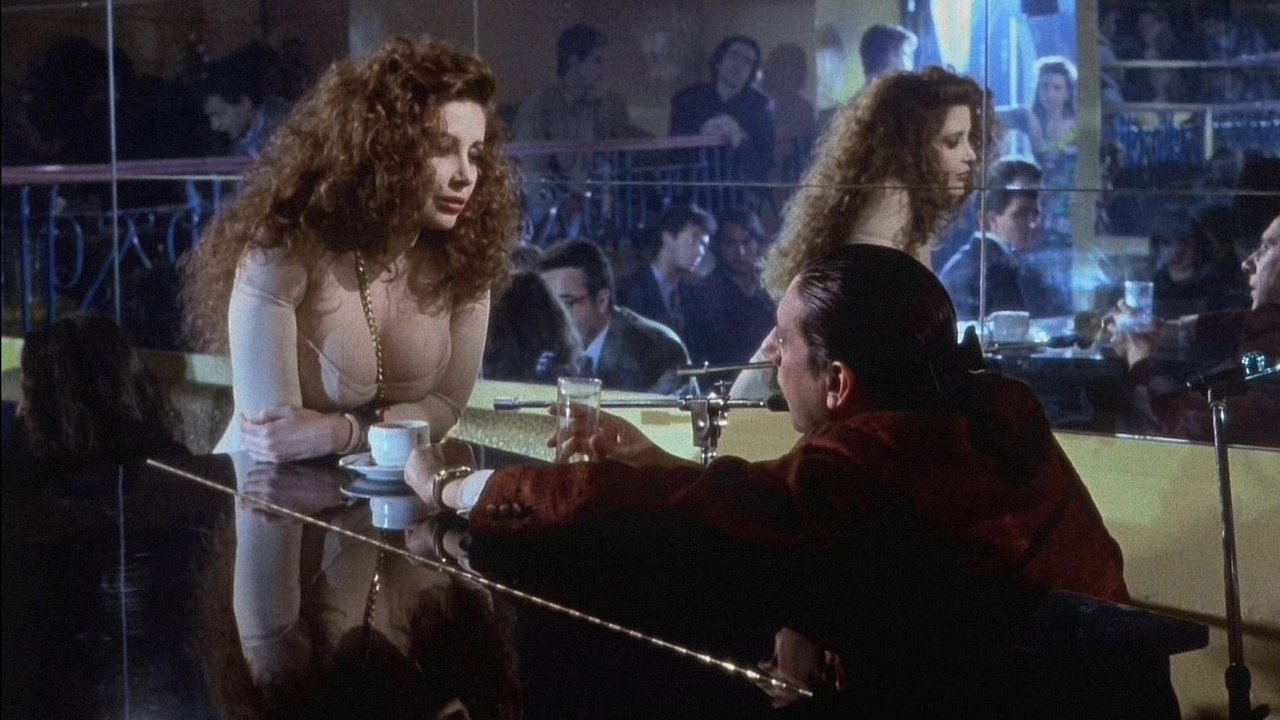

The premise drifts in with deceptive calm. Paolo (Sergio Castellitto), a divorced piano player working in a seaside resort town, encounters the stunningly beautiful Francesca (Francesca Dellera). An intense, almost instantaneous connection sparks, rapidly escalating into an all-consuming affair. They retreat to Paolo's isolated beach house, sealing themselves off from the world, embarking on a journey of obsessive eroticism. It sounds almost like a standard European art-house drama, until Ferreri, ever the provocateur, pushes the boundaries of that obsession into far darker, more primal territory. The sun-drenched Italian coast becomes an ironic backdrop to an increasingly claustrophobic and disturbing psychological deep dive.

Ferreri's Feast of Ideas

You can't really talk about The Flesh without acknowledging its director. Marco Ferreri, who scandalized audiences nearly two decades earlier with the scatological satire La Grande Bouffe (1973), wasn't one for subtlety or easy answers. His films often poke and prod at societal norms, bourgeois complacency, and the often-grotesque nature of human desire. Here, he seems fascinated by the idea of love as the ultimate act of consumption. In a world saturated with things to buy and own, does desire inevitably lead to wanting to incorporate the object of affection entirely? Ferreri presents this challenging, potentially repellent idea with a strange, almost deadpan seriousness that forces you to confront it, even as you might recoil. The film competed for the Palme d'Or at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival, where, true to Ferreri's form, it sharply divided critics – hailed by some as a profound statement on modern alienation, dismissed by others as gratuitously shocking or even misogynistic. Ferreri reportedly embraced the controversy, viewing it as proof his work had hit a raw nerve.

The Weight of Obsession

The film rests heavily on the shoulders of its two leads. Sergio Castellitto, who would become one of Italy’s most respected actors, is utterly compelling as Paolo. He doesn't play him as a monster, but as a man hollowed out by a profound loneliness, seeking an impossible completeness in Francesca. His descent isn't sudden; it's a gradual surrender to an overwhelming impulse, making it all the more chilling. Castellitto conveys the vulnerability beneath the obsession, the desperation driving his increasingly extreme actions.

Francesca Dellera, a striking beauty who had a somewhat meteoric and controversial career herself in Italian media, portrays Francesca with a deliberate, almost unsettling passivity. Is she a willing participant, an empty vessel for Paolo's projections, or something else entirely? Her enigmatic presence fuels the film's ambiguity. She is both the object of desire and a catalyst, her seeming acquiescence making Paolo’s spiraling fixation possible. Their dynamic is electric but deeply uncomfortable, a portrayal of codependency taken to its most extreme conclusion.

Beyond the Taboo (Spoiler Warning!)

Yes, the film goes there. The final act, involving Paolo's attempt to preserve Francesca's body and his eventual implied act of cannibalism, is the film's most notorious element. But to dismiss it as mere shock value misses Ferreri's likely allegorical intent. It’s the horrifying endpoint of consumerist desire – wanting to possess someone so completely that you literally consume them, incorporating them into yourself. It's a brutal metaphor for the ways relationships can sometimes seek to absorb individuality, pushed to a grotesque, taboo-shattering extreme. Finding this on VHS, perhaps nestled between more conventional thrillers or dramas, must have been quite the jolt back in the day – a reminder that cinema could still venture into truly transgressive territory. It’s a far cry from the easily digestible fare that often dominated rental shelves.

A Lingering Aftertaste

The Flesh isn't an easy watch, nor is it meant to be. It’s provocative, disturbing, and will likely leave many viewers cold or even disgusted. Yet, there's an undeniable power to its central performances and Ferreri's unflinching Gaze. It gnaws at you, forcing questions about the nature of love, possession, and the void that consumer culture perhaps fails to fill. It feels very much like a product of its specific time – the tail end of the excessive 80s bleeding into the uncertain 90s, grappling with satiety and spiritual emptiness. It certainly wasn't a box office smash, its challenging nature ensuring a more cult, arthouse trajectory.

Rating: 6/10

This rating reflects the film's undeniable artistic ambition and powerful performances, particularly Castellitto's, weighed against its challenging, often alienating subject matter and a narrative that prioritizes provocative ideas over conventional engagement. It earns points for sheer audacity and for Marco Ferreri’s uncompromising vision, even if that vision leads down a very dark path. It’s technically accomplished and thematically rich, but its barrier to entry is high, and its central taboo will be insurmountable for many.

The Flesh remains a potent, if deeply unsettling, piece of early 90s European cinema. It’s a film less “enjoyed” in the traditional sense and more wrestled with – a stark reminder from the VHS vaults that love, taken to its absolute extreme, can look terrifyingly like consumption.