There's a particular quiet that settles over you after watching Randa Haines’ Children of a Lesser God (1986). It’s not just the absence of sound that lingers, but the resonance of unspoken emotion, the weight of communication attempted, achieved, and sometimes painfully failed. It’s a film that asks you to listen not just with your ears, but with your eyes, your heart, and your empathy, forcing a confrontation with the assumptions we often make about connection and understanding. Watching it again on a fuzzy VHS tape years later, that feeling hasn't diminished; if anything, the film's patient exploration of difference feels even more vital.

Worlds Colliding Gently

The premise is deceptively simple: James Leeds (William Hurt), an idealistic and somewhat cocky new speech teacher, arrives at a school for the Deaf in Maine. He’s determined to teach his students to speak and lip-read, convinced it’s the key to navigating the hearing world. But he quickly runs up against the fierce intelligence and defiant silence of Sarah Norman (Marlee Matlin), a former student now working as a janitor, who refuses to speak, communicating solely and powerfully through American Sign Language (ASL). What unfolds is far more than a teacher-student dynamic or a conventional romance; it’s a profound exploration of identity, prejudice (both overt and unintentional), and the complex negotiation required when two profoundly different worlds attempt to merge.

A Debut That Echoed Through Cinema

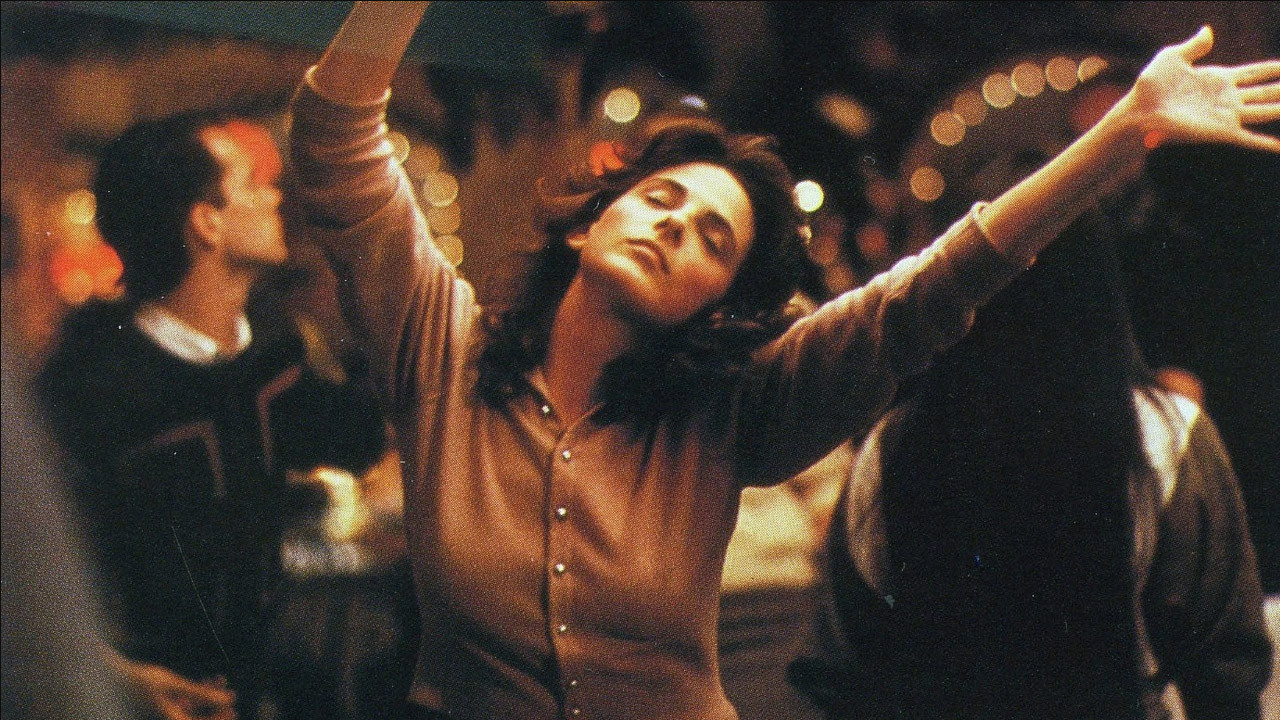

It's impossible to discuss Children of a Lesser God without focusing on the performances, particularly Marlee Matlin's astonishing debut. In a role that could have easily felt passive or opaque, Matlin delivers a hurricane of emotion – fierce independence, vulnerability, simmering anger, and deep-seated hurt – all conveyed with breathtaking clarity through her signing, her eyes, and her entire physical presence. It's a performance forged in authenticity, demanding the audience meet her on her terms. It’s no small wonder she became, and remains, the first and only Deaf performer to win the Academy Award for Best Actress, and the youngest winner in that category at 21.

Interestingly, the studio reportedly considered more established hearing actresses like Meryl Streep, but both William Hurt and director Randa Haines fought passionately for casting a Deaf actress. Matlin, discovered during a stage production of the play on which the film is based (written by Mark Medoff, who co-adapted the screenplay with Hesper Anderson), didn't just learn her lines; she reportedly learned Hurt's as well, allowing her to anticipate his cues perfectly despite not hearing them. This behind-the-scenes dedication mirrors the film's own narrative of finding ways to connect across sensory divides.

Hurt's Sensitive Counterpoint

Opposite Matlin, William Hurt, then near the peak of his 80s stardom after films like Body Heat (1981) and his Oscar win for Kiss of the Spider Woman (1985), provides a crucial anchor. His James Leeds is flawed – initially patronizing, driven by ego as much as idealism – but Hurt imbues him with a sensitivity and a genuine yearning for connection that makes his journey believable. He learns ASL for the role, and his scenes with Matlin crackle with an intensity born from the sheer effort of communication. It’s a performance that requires him to react as much as act, mirroring the audience’s own process of learning to understand Sarah through her signs. Supporting actress Piper Laurie also adds grounding warmth as Sarah's estranged mother, representing the hearing world Sarah feels rejected by.

More Than Just a Love Story

While romance is central, the film transcends simple love story tropes. Randa Haines, in only her second feature film, directs with a gentle, observational style, allowing the emotional weight to build organically. She skillfully visualizes the conflict: James pushing Sarah towards the hearing world, Sarah fiercely defending her identity within Deaf culture. Is love enough to bridge such a fundamental gap? Can one person truly understand another's reality without living it? The film doesn't offer easy answers. It portrays the frustrations, the compromises, and the moments where understanding breaks down, making the moments of genuine connection all the more powerful. It cost around $10.5 million to make but resonated deeply, earning over $100 million at the worldwide box office (adjusted for inflation, that's a significant success!), proving audiences were ready for this kind of challenging, human story.

The film wasn't just a critical and commercial success (earning five Oscar nominations including Best Picture); it was a cultural moment. It brought ASL and Deaf culture into the mainstream spotlight in an unprecedented way, sparking conversations about representation and accessibility that continue today. Seeing it back then, maybe rented from a local store with its distinctive worn cover, felt important. It was a drama that felt adult, complex, and deeply human amidst the louder fare often dominating the shelves.

Listening Beyond Words

Children of a Lesser God remains a potent and moving piece of cinema. Its pacing is deliberate, reflective of the time and the careful unfolding of its central relationship. Some might find James's initial approach grating by modern standards, but it serves the narrative arc of his own education. The core strength lies in its unflinching honesty about the difficulties of bridging profound differences and its celebration of communication in all its forms. Matlin's performance remains a landmark, a testament to the power of acting that transcends spoken language.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's groundbreaking nature, the unforgettable power of Marlee Matlin's debut, William Hurt's sensitive performance, and its enduringly relevant exploration of communication, identity, and connection. It’s a film that stays with you, prompting reflection long after the credits roll, reminding us that truly listening often involves more than just hearing. What does it truly mean to meet someone where they are, rather than demanding they come to you? Children of a Lesser God leaves you pondering that essential human question.