How do you follow a monolith? Not just the enigmatic black slab central to Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece, but the film itself – 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), a work so profound, so visually revolutionary, it reshaped cinema’s possibilities. Imagine the sheer audacity, then, of tackling its sequel. Yet, that’s precisely the challenge writer-director Peter Hyams accepted with 2010: The Year We Make Contact (1984), a film that arrived on video store shelves offering not cosmic ambiguity, but a gripping space procedural laced with Cold War anxieties. Renting this one always felt different; less about confronting the infinite, more about embarking on a tangible, tense mission.

### A Different Kind of Odyssey

Where Kubrick painted with abstraction and cosmic awe, Hyams grounds his narrative firmly in the geopolitical realities of the early 80s. The Cold War hangs heavy in the void as a joint US-Soviet mission races towards Jupiter aboard the Soviet vessel Leonov to investigate the derelict Discovery One and the looming monolith left orbiting the gas giant. This immediately sets a different tone: less metaphysical puzzle, more pragmatic problem-solving under immense pressure. Hyams, who famously sought and received Kubrick's blessing (reportedly with the advice, "Don't be afraid to make it your own"), wisely chooses not to mimic Kubrick's style. Instead, he delivers a taut, handsome thriller that prioritizes plot clarity and character interaction over philosophical wonder. Some might see this as a step down, but watching it again now, there's an undeniable competence and narrative drive that makes 2010 a compelling watch on its own terms.

### Humanising the Infinite

Central to the film's success are the performances. Roy Scheider, stepping into the role of Dr. Heywood Floyd (previously played by William Sylvester in 2001), brings a weary pragmatism and quiet authority that anchors the film. He's less a visionary administrator and more a seasoned diplomat navigating treacherous political waters millions of miles from home. His interactions with his Soviet counterpart, Captain Tanya Kirbuk, played with steely command by Helen Mirren, form the film's emotional core. Their gradual thawing from suspicion to mutual respect amidst escalating tensions back on Earth provides a hopeful counterpoint to the era's real-world paranoia. And let's not forget John Lithgow as Walter Curnow, the affable but anxious engineer whose fear of space travel (“I’m afraid of heights!” delivered while literally floating in space) provides moments of welcome humanity – and a touch of subtle humour – amidst the cosmic drama. These actors make the extraordinary situation feel relatable through grounded, believable portrayals.

### Crafting Jupiter on Earth

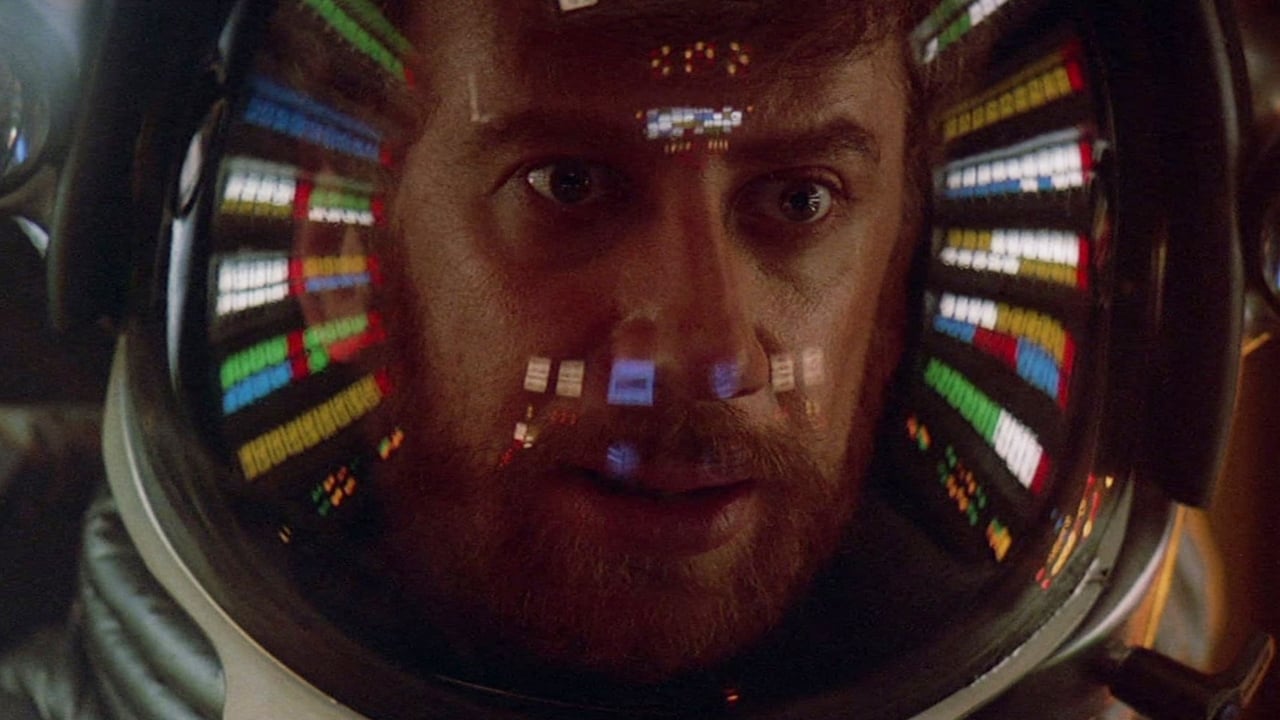

Visually, 2010 is a fascinating product of its time. Made for a substantial $28 million (around $82 million in today's money), the film boasts impressive model work and practical effects supervised by the legendary Richard Edlund (known for Star Wars (1977)). The Leonov and Discovery spacecraft have a tangible weight and detail characteristic of the best pre-CGI sci-fi. Hyams, taking the bold step of serving as his own director of photography, gives the film a distinct look – often favouring claustrophobic interiors lit with functional, sometimes stark, lighting, contrasting sharply with the expansive, balletic visuals of 2001. While the depiction of Jupiter might not achieve the psychedelic majesty of its predecessor's stargate sequence, the swirling cloudscapes and the emergence of the monolith possess a genuine sense of scale and menace. This was ambitious visual storytelling, pushing the boundaries of what was possible before digital tools became ubiquitous. You could almost feel the hum of the VCR working overtime rendering those complex shots on your CRT screen back in the day.

### Explaining the Unexplainable

One of the most debated aspects of 2010 is its willingness to provide answers where 2001 offered only questions. We learn the reason for HAL 9000’s murderous breakdown – conflicting orders creating a digital paradox – a logical, almost mundane explanation drawn directly from Arthur C. Clarke's sequel novel. Bringing HAL back online, voiced once again with chilling politeness by Douglas Rain, is genuinely unnerving. The film also offers a more direct (though still awe-inspiring) explanation for the monolith's purpose as an accelerator of evolution, culminating in Jupiter's transformation into a new star. Does demystifying these elements diminish the original? Perhaps for some. But Hyams and Clarke (who makes a cameo appearance on a fictional TIME magazine cover within the film) arguably provide satisfying narrative closure, transforming the existential dread of 2001 into a message of hope and potential rebirth, albeit one delivered with a stark warning: "All these worlds are yours except Europa. Attempt no landing there."

### A Legacy in the Shadow

2010: The Year We Make Contact inevitably lives in the shadow of its monumental predecessor. It doesn't aim for the same transcendent heights, and wisely so. What it achieves instead is intelligent, well-crafted, and suspenseful science fiction cinema. It grapples with big ideas – international cooperation, the nature of intelligence (artificial and alien), humanity's place in the cosmos – but packages them within a more conventional, accessible narrative structure. It may not inspire the same level of philosophical debate as 2001, but it offers a compelling story, strong performances, and impressive visuals that hold up remarkably well. It was a staple of the video store sci-fi section for a reason – a reliable, engrossing journey to the outer planets that delivered spectacle and substance. Its respectable $40 million domestic box office (around $117 million today) proved there was an audience eager to revisit Clarke's universe, even through a different lens.

Rating: 7.5/10

Justification: While not the game-changing masterpiece 2001 was, 2010 is a highly competent, intelligent, and visually impressive sci-fi film. Strong performances, a compelling Cold War narrative layered onto the space exploration, and fascinating (for the era) practical effects make it a rewarding watch. It successfully translates Clarke's novel to the screen and provides satisfying, if less profound, answers. It loses points primarily for the inherent impossibility of matching its predecessor's iconic status and for occasionally favouring exposition over mystery, but stands firmly as quality 80s sci-fi.

Final Thought: 2010 reminds us that sometimes, the journey towards understanding, even if it demystifies the magic slightly, can be just as compelling as the initial encounter with the unknown. It’s a film that respected its origins while confidently charting its own course through the cosmos – and our VCRs.