Okay, settle in, grab your preferred beverage – maybe something classic? – because we're pulling a truly unique tape off the shelf today. It’s one that, even decades later, feels startlingly inventive, a technical marvel wrapped around a surprisingly poignant core. We’re talking about Woody Allen's 1983 creation, Zelig.

### The Man Who Wasn't There (But Somehow Was)

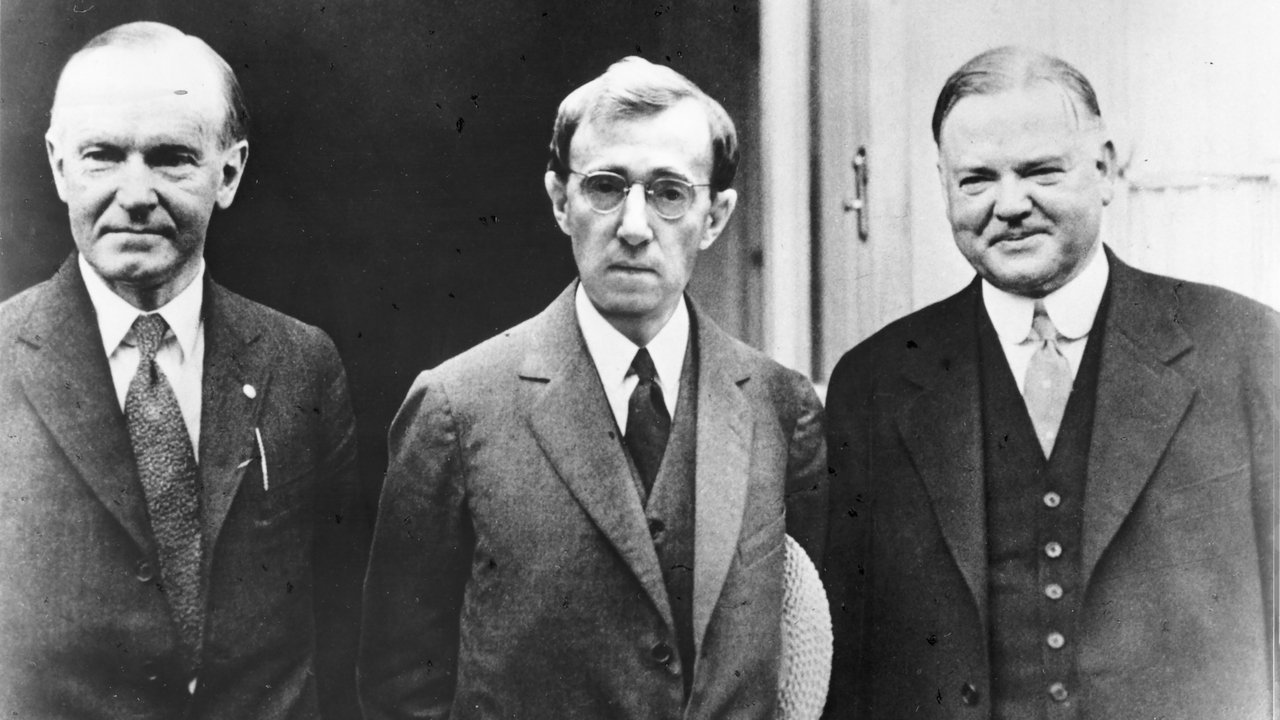

What if a man's desire to be liked, to simply fit in, was so overwhelming that it physically manifested? That’s the central, brilliantly absurd premise of Zelig. Presented as a meticulously crafted faux-documentary, complete with aged newsreel footage, solemn narration (Patrick Horgan), and interviews with contemporary intellectuals (like Susan Sontag and Irving Howe, playing themselves), the film chronicles the strange case of Leonard Zelig (Woody Allen). In the roaring 1920s, Zelig becomes a bizarre international phenomenon – the "Human Chameleon," a man who involuntarily takes on the physical and psychological characteristics of whomever he's near. He becomes Black playing jazz with Black musicians, overweight among rotund gentlemen, a psychoanalyst among psychoanalysts. He’s everywhere and nowhere, a perfect mirror reflecting the world around him, utterly devoid of a self.

### A Disappearing Act of Cinematic Genius

Let's just pause and appreciate the sheer audacity and technical wizardry on display here, especially for 1983. Forget CGI; this was the era of painstaking optical printing and sheer analog ingenuity. Woody Allen and his legendary cinematographer Gordon Willis (the visual architect behind The Godfather films and Allen's own Annie Hall) went to extraordinary lengths to seamlessly insert Allen's Zelig into actual archival footage from the 20s and 30s.

This wasn't just a matter of clever editing. They sourced vintage film cameras and lenses. They physically damaged the new film stock – scratching it, throwing dirt on it, duplicating it repeatedly – to perfectly match the grain, contrast, and wear-and-tear of the decades-old newsreels. The compositing work, blending the newly shot elements of Allen with historical figures like Al Capone, Pope Pius XI, and even Adolf Hitler, was groundbreaking. Joel Hynek and his team at R/Greenberg Associates achieved effects that still look remarkably convincing, requiring immense precision and patience in an era long before digital tools streamlined such processes. Hearing stories about the meticulous frame-by-frame work involved truly deepens one's appreciation; it wasn't just filmmaking, it was practically alchemy. This dedication to authenticity is the film's visual language, selling the impossible premise with astonishing success. Imagine seeing this on a slightly fuzzy VHS copy back in the day – the blend might have seemed even more uncannily real.

### Beneath the Chameleon Skin

While the technical brilliance is undeniable, Zelig resonates beyond its gimmickry. Allen portrays Zelig not just as a punchline, but as a figure of profound pathos. His condition, while played for absurdist humor (the novelty songs, the dance craze), stems from a deep, aching need for acceptance, a fear of standing out so crippling that he literally vanishes into the crowd. It’s a performance of subtle physical comedy and underlying sadness. Does his blankness make him innocent, or complicit? The film leaves that unsettling question hanging.

Counterbalancing Zelig's emptiness is Mia Farrow as Dr. Eudora Fletcher, the earnest psychiatrist determined to understand and cure him. Farrow brings a necessary warmth and intellectual grounding to the proceedings. Her character represents reason and empathy attempting to grapple with the inexplicable, and her evolving relationship with Zelig provides the film's emotional core. Their dynamic explores whether finding a 'self' is even possible, or desirable, once you’ve become a reflection.

### Echoes in the Funhouse Mirror

What does Zelig's story say about us? The film uses its historical setting to explore timeless themes: the desperate yearning for conformity, the fickle nature of fame, the media's power to create and destroy icons, and the very construction of identity. Zelig becomes whatever society wants or projects onto him – a medical marvel, a dangerous anomaly, a novelty act, a symbol. You watch him navigate the jazz age, the rise of fascism, the glare of the public eye, and you can't help but wonder: how different is his plight from the pressures we feel today to curate our personas, to 'fit in' online or offline? Has the desperate need for validation simply found new, digital avenues? The film feels surprisingly prescient in its exploration of image and the void that can lie beneath it.

The mockumentary format allows Allen to blend sharp satire with these deeper reflections. The deadpan narration, the fabricated historical analysis, the pitch-perfect period details – it all creates a unique tone, simultaneously funny, clever, and melancholic. It’s a film that invites contemplation long after the credits roll.

***

Rating: 9/10

The score reflects Zelig's stunning technical innovation, its brilliantly executed concept, and its enduring thematic resonance. While its specific brand of intellectual humor might not connect with everyone, its artistry and the haunting questions it poses about identity and conformity are undeniable. It's a high point in Woody Allen's filmography and a masterclass in mockumentary filmmaking that feels just as inventive now as it did spilling from a well-worn VHS tape.

Final Thought: Zelig remains a fascinating paradox – a film about profound emptiness achieved through astonishing cinematic fullness, leaving you pondering the chameleon that perhaps lurks within us all.