There's a certain kind of gray that only exists in memory and old black-and-white films. It’s the color of cigarette smoke curling in a dimly lit deli, the shade of a worn suit on a man perpetually down on his luck but never quite out of hope. It’s the color palette of Woody Allen’s 1984 gem, Broadway Danny Rose, a film that feels less like watching a movie and more like eavesdropping on a group of old comics swapping poignant “you won’t believe this” stories over pastrami sandwiches.

Tales from the Carnegie Deli

The film unfolds through a framing device that’s become almost as legendary as the movie itself: a gathering of real-life comedians (including Sandy Baron, Corbett Monica, and Jackie Gayle) at New York's famed Carnegie Deli, reminiscing about the quintessential purveyor of third-rate novelty acts, Danny Rose (Woody Allen). Danny represents the absolute fringe of show business – his clients include balloon folders, one-legged tap dancers, and glass-playing musicians. He’s a perpetual optimist, fiercely loyal to his stable of hopeless performers, always believing their big break (and consequently, his) is just around the corner. Allen, stepping away from his usual neurotic intellectual persona, embodies Danny with a surprising warmth and vulnerability. It's arguably one of his most sympathetic and purely heartfelt performances; you genuinely root for this guy, even as you see the next disaster looming.

A Favor for Lou

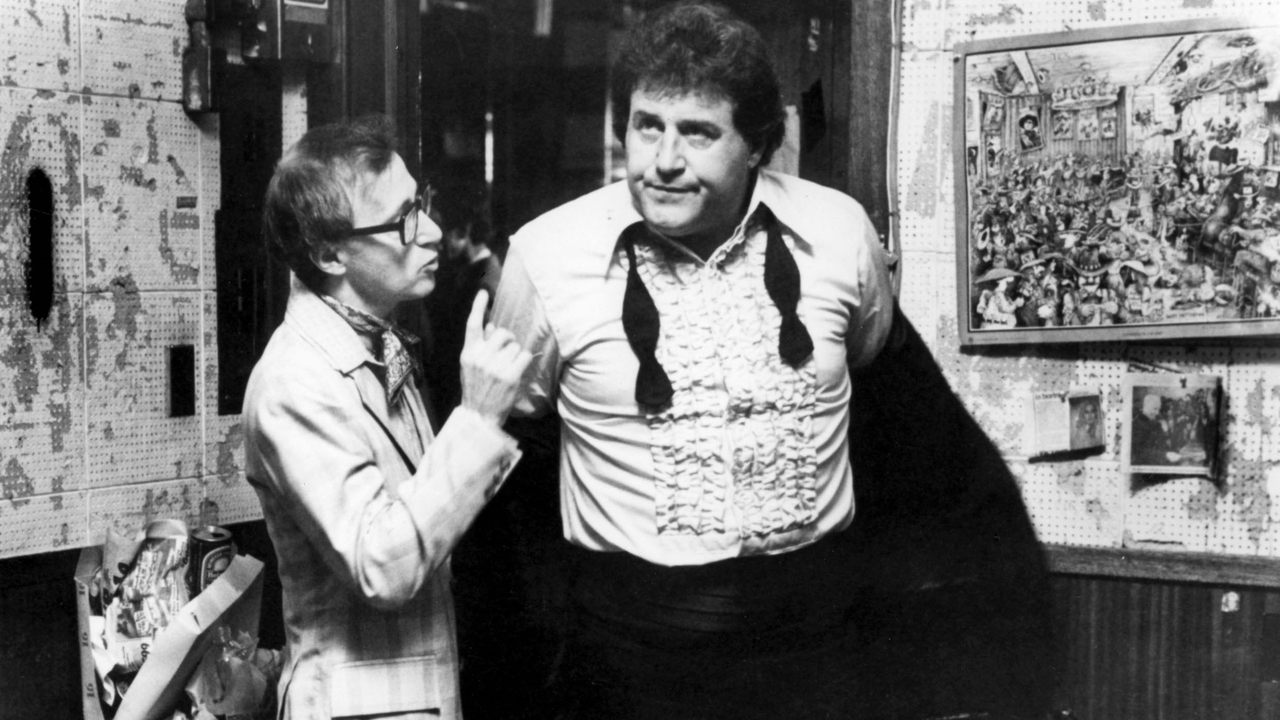

The main narrative kicks off when Danny’s one potentially viable client, nostalgic lounge singer Lou Canova (Nick Apollo Forte), starts gaining traction. Lou, however, comes with baggage: a demanding mistress, Tina Vitale (Mia Farrow), whom he insists Danny escort to his big comeback gig at the Waldorf Astoria as his “beard.” Tina, hidden behind perpetual dark sunglasses and emanating a tough, seen-it-all weariness, is initially presented as trouble incarnate. This setup – the hapless agent, the needy crooner, the volatile girlfriend – could easily slide into farce, and there are certainly comedic moments, often involving mistaken identity and low-level mobsters who think Danny is stepping out with Tina.

But Allen, as both writer and director, steers the film toward something more profound. It becomes a study in loyalty, integrity, and the peculiar moral codes that exist even on the bottom rungs of the entertainment ladder. The black-and-white cinematography by the legendary Gordon Willis (who shot The Godfather and Allen’s own Annie Hall), isn't just a stylistic choice; it lends the film a timeless, almost fable-like quality, perfectly capturing the slightly seedy, slightly magical world Danny inhabits. It strips away the 80s sheen, making the story feel like it could have happened anytime in the previous fifty years.

Unlikely Stars Shine Bright

While Allen delivers a wonderfully specific performance, the film truly belongs to his co-stars. Mia Farrow, in a role radically different from her usual ethereal screen presence, is a revelation. Hidden behind those oversized shades and affecting a brassy, husky voice, she crafts a character who is simultaneously tough, fragile, and surprisingly perceptive about the men in her life. It's a performance that garnered significant acclaim at the time, reminding audiences of her considerable range. It feels like a genuine transformation, not just an actress playing dress-up.

And then there's Nick Apollo Forte. In a move typical of Allen's knack for casting authenticity, Forte wasn't a seasoned actor but a real-life New Jersey lounge singer whom Allen discovered. This background infuses Lou Canova with an effortless realism. He’s got the charm, the voice (yes, he does his own singing, including the infectious original song "Agita"), and that particular blend of ego and insecurity common to performers who’ve tasted just enough success to crave more. Forte’s naturalism makes Lou’s casual betrayals and easygoing charisma utterly believable. Reportedly, finding Forte was key; Allen had considered other options, including Danny Aiello and even Robert De Niro (imagine that!), before Forte’s audition sealed the deal.

A Bittersweet Valentine

Broadway Danny Rose isn't just about the laughs, though there are plenty, often stemming from Danny's perpetual motion panic and the absurdity of his predicaments (like being chased through a warehouse full of parade floats). It digs deeper, questioning what constitutes success and whether unwavering loyalty is a virtue or a handicap in a cutthroat world. Does Danny’s refusal to compromise his integrity, even for his “stars,” make him a fool or a quiet hero? The film doesn't offer easy answers.

Shot on a modest budget (around $8 million) even for the time, it performed respectably ($10.6 million gross) and earned Allen Oscar nominations for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay. It feels like a very personal film, a valentine to a bygone era of show business populated by characters clinging to dreams long after the spotlight has faded. I remember renting this on VHS, probably nestled between bigger blockbusters, and being utterly charmed by its unique tone – funny, sad, and deeply human all at once. It felt different, quieter, more observant than much of the era's output.

The film’s climax, involving Thanksgiving Day, frozen turkeys, and a moment of quiet grace, resonates long after the credits roll. It suggests that perhaps the greatest rewards aren't found on the grand stages like the Waldorf, but in the simple connections forged in the face of shared absurdity.

Rating: 8.5/10

This rating reflects the film's masterful blend of humor and pathos, its unforgettable characters brought to life by pitch-perfect performances (especially from Farrow and the perfectly cast Forte), and its evocative atmosphere created by Allen's writing/directing and Willis's stunning cinematography. It's a deceptively simple story told with immense heart and skill, earning its sentimentality rather than forcing it. A minor deduction accounts for the fact that its specific milieu might feel niche to some, but its universal themes of loyalty and dignity shine through brightly.

Broadway Danny Rose remains one of Allen’s most purely enjoyable and emotionally satisfying films, a bittersweet ode to the lovable losers and unsung saints of the world. It leaves you not just with laughter, but with a warm ache of recognition for the Dannys we might know – or the Danny we sometimes wish we could be. What’s more valuable in the end: fleeting fame or a sandwich named in your honor at the Carnegie Deli?