There's a certain kind of hazy beauty to Hammett (1982), a film that feels less like a straightforward narrative and more like a half-remembered dream of what a noir film should be. It arrived on VHS shelves, often tucked away in the drama or mystery sections, carrying the weight of its famously troubled production like a trench coat heavy with rain. Pulling that tape out, maybe an Orion Pictures release if memory serves, felt like unearthing something slightly illicit, a story whispered rather than shouted.

A Writer Lost in His Own Ink

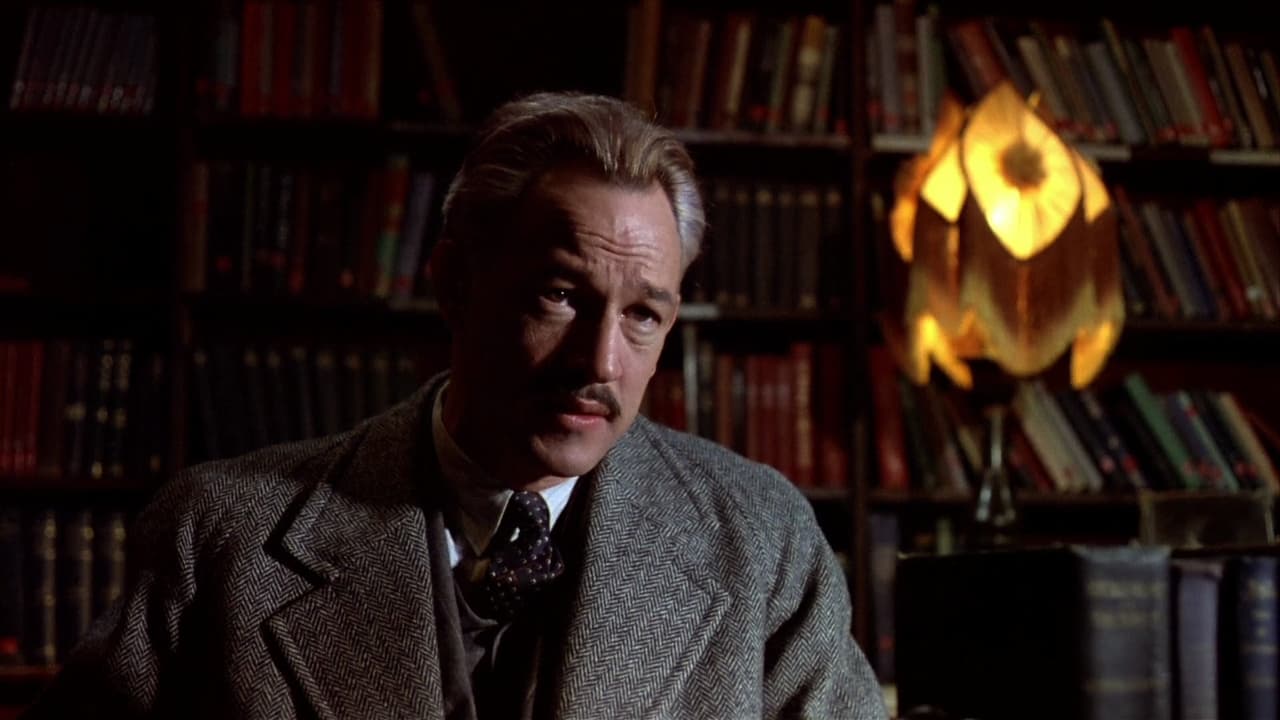

The premise itself is intoxicating: Dashiell Hammett, the legendary pulp author, played with a weary, watchful intelligence by Frederic Forrest, gets pulled from his writer's desk back into the shadowy world of private investigation he thought he'd left behind. Set in a meticulously crafted, almost suffocatingly stylized 1928 San Francisco, the film plunges Hammett into a labyrinthine plot involving missing persons, blackmail, and the kind of colourful, dangerous characters that could have sprung directly from his own typewriter. The line between the creator and his creations begins to blur almost immediately. Doesn't that transformation – the observer forced to become the participant – echo the very core of the detective genre itself?

Shadows and Style: A Troubled Vision

This wasn't just another detective story, though. This was a project born under the ambitious, often tumultuous banner of Francis Ford Coppola's Zoetrope Studios, with the celebrated German director Wim Wenders (known for meditative works like Paris, Texas (1984)) initially at the helm. What emerges on screen is a fascinating, sometimes frustrating, blend of sensibilities. Wenders' eye for atmosphere and existential drift clashes, sometimes beautifully, sometimes awkwardly, with what feels like Coppola's more conventional noir instincts, reportedly imposed during extensive reshoots that significantly altered the film.

The production saga is almost as legendary as the fictional mystery. Years in development (based on a novel by Joe Gores), script rewrites galore (credited to Ross Thomas and Thomas Pope, among others), and rumours of Wenders essentially being sidelined by Coppola – it all contributes to the film's unique, slightly spectral quality. Knowing this backstory doesn't just feel like trivia; it informs the viewing experience. You start looking for the seams, wondering which scenes belong to which vision. It cost a hefty $12-13 million back then (imagine that budget today!), a sum it sadly never came close to recouping, grossing under $3 million. This commercial failure perhaps cemented its status as a cult curio, something sought out rather than stumbled upon.

Performances Forged in Fog

Despite the behind-the-scenes drama, the performances often shine through the stylized gloom. Frederic Forrest, fresh off his Oscar-nominated turn in The Rose (1979) and a key role in Coppola's Apocalypse Now (1979), embodies Hammett not as a hard-boiled hero, but as an intelligent, somewhat frail man grappling with his past and the allure of the dangerous stories he tells. He carries the film with a quiet intensity. Alongside him, Peter Boyle (forever beloved as the monster in Young Frankenstein (1974)) brings a gruff, world-weary energy as Jimmy Ryan, Hammett's former Pinkerton mentor who drags him back into the muck. And Marilu Henner, radiating classic Hollywood glamour, adds a vital spark as the enigmatic Crystal Ling. Each actor feels carefully placed within the film's painterly compositions, contributing to its almost theatrical feel.

A Film Set World

One of the most striking aspects of Hammett is its look. Forget gritty realism; this San Francisco feels entirely constructed, a studio-bound dreamscape courtesy of legendary production designer Dean Tavoularis (another Coppola regular from The Godfather (1972) and Apocalypse Now). The Chinatown sequences, in particular, are breathtakingly artificial, bathed in neon glow and perpetual mist. It’s a deliberate choice, emphasizing the film's meta-narrative – we're not just in 1928 San Francisco, we're in Hammett's idea of 1928 San Francisco, a world built from words and shadows. Does this artificiality distance the viewer, or pull them deeper into the writer's subjective experience? I find it does the latter, creating a unique, almost hypnotic atmosphere. The cinematography, handled by veterans Joseph Biroc and Philip H. Lathrop, perfectly captures this heightened reality.

Legacy of a Near Miss

Hammett isn't a perfect film. The narrative can feel convoluted, a likely casualty of the reshoots and competing visions. The pacing sometimes lags, caught between Wenders' contemplative style and the demands of a traditional mystery plot. Yet, its ambition is undeniable. It's a film about storytelling, about the seductive power of crime fiction and the way myths are constructed, both on the page and in life. Finding this on VHS felt like discovering a missing chapter in film noir history, a fascinating "what if?" brought partially to life. It wasn't the blockbuster follow-up Zoetrope desperately needed after One from the Heart (1981), but its artistic merit, however compromised, lingers.

Rating: 7/10

The score reflects a film brimming with atmosphere, style, and intelligent performances, particularly from Forrest. It's a visual treat with a compelling central idea. However, the undeniable marks of its troubled production – the narrative inconsistencies and occasionally uneven tone – prevent it from achieving true greatness. It earns its points for ambition, aesthetic beauty, and for Forrest's portrayal, but loses some for the slightly fractured storytelling that hints at the directorial conflict behind the scenes.

Ultimately, Hammett remains a captivating enigma, a beautifully flawed ode to the very genre it depicts. It’s a film that invites you to lean in, to appreciate the shadows and whispers, even as you sense the ghosts of the movie it might have been. It's a perfect find for a rainy night, a reminder of a time when studios took big, strange swings, even if they didn't always connect cleanly. What stays with you isn't just the plot, but the pervasive mood – the fog, the secrets, the writer lost in his own creation.