Before the soaring fantasies and wartime heartbreaks that would define Studio Ghibli, there was a quieter magic brewing. Imagine stumbling upon a lone VHS tape, perhaps tucked away in the "Children's/Family" section of the local video store, its cover art depicting a simple, almost rustic scene: a young man and his cello. This was often how many of us discovered Gauche the Cellist (セロ弾きのゴーシュ, Serohiki no Gōshu), a 1982 film directed by Isao Takahata. It wasn't bombastic, it wasn't filled with the high-octane action often associated with 80s anime, but it possessed a gentle, resonant quality that lingers long after the tape stopped whirring. Discovering it felt like finding a hidden channel, one broadcasting pure, unadulterated heart.

A Humble Beginning, A Frustrated Musician

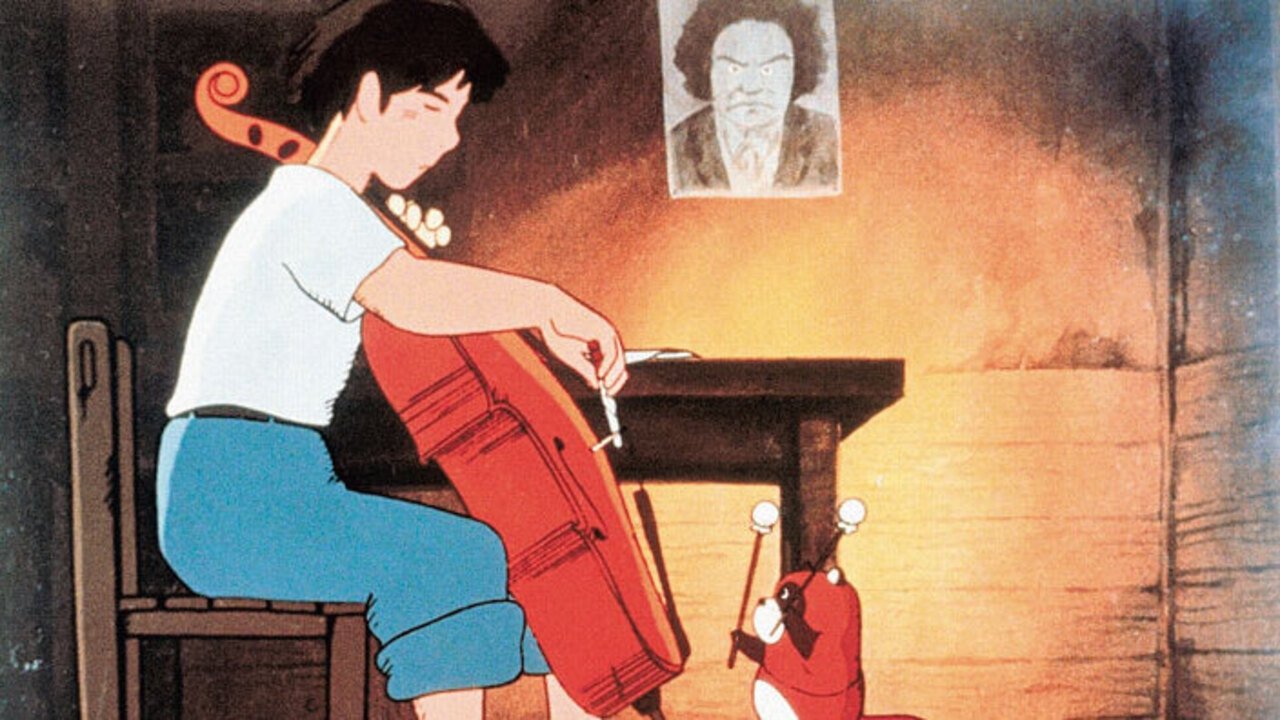

The film, based on a short story by the beloved Japanese author Kenji Miyazawa, centers on Gauche (Hideki Sasaki), a diligent but technically lacking cellist in a small town orchestra. We first meet him enduring harsh criticism from the conductor. He’s earnest, he tries hard, but his playing lacks soul, precision, and the emotional depth required for Beethoven's Sixth Symphony (the "Pastoral"), which the orchestra is rehearsing. Deflated, Gauche retreats to his solitary cottage outside town to practice, his frustration almost radiating from the screen. There’s a relatable authenticity to his struggle; who hasn't felt inadequate when pouring their heart into something, only to fall short? Sasaki's voice acting perfectly captures this blend of determination and self-doubt, making Gauche instantly sympathetic.

Lessons from the Wild

It's in the quiet solitude of his cottage that the film truly finds its unique rhythm. Over successive nights, Gauche receives unexpected visitors: a calico cat (Fuyumi Shiraishi), a cuckoo bird, a tanuki (racoon dog - voiced by Kaneta Kimotsuki), and finally, a field mouse and her sick son. Each animal arrives with a specific, often seemingly selfish, musical request. The cat wants him to play Schumann's "Träumerei" to cure its tomato-induced indigestion (a wonderfully bizarre detail!), the cuckoo insists he practice scales for hours, the tanuki needs help with rhythm using its drum. Initially annoyed, Gauche reluctantly obliges, and through these strange, almost fable-like encounters, he unknowingly refines his craft. He learns rhythm from the tanuki, dexterity from the cuckoo's demanding repetition, and, crucially, emotional expression as he plays to soothe the tiny, ailing mouse. These sequences are the heart of the film, blending Miyazawa's reverence for nature with a whimsical exploration of how art connects us, even across species.

The Gentle Hand of a Future Master

Watching Gauche today offers a fascinating glimpse into the developing artistry of Isao Takahata, years before he would co-found Studio Ghibli and give us masterpieces like Grave of the Fireflies (1988) and Only Yesterday (1991). His characteristic patience and observational style are already fully present. The animation, produced by Oh! Production (which employed many future Ghibli animators), possesses a warm, hand-drawn quality that feels incredibly nostalgic now. While simpler than later Ghibli works, the attention to detail in Gauche's cramped cottage, the expressions on the animals' faces, and the depiction of Gauche's playing (both awkward and, later, assured) is remarkable.

Interestingly, the film’s production was notoriously long, reportedly taking around six years to complete after starting in the mid-70s. This lengthy gestation period perhaps speaks to Takahata's meticulous nature, his refusal to rush the quiet moments that define the film's soul. He allows scenes to breathe, focusing on the process – the repetitive scraping of the bow, the focused intensity on Gauche’s face, the subtle shifts in the natural world outside his window. It’s a pace that demands patience, a far cry from the rapid-fire editing common today, but deeply rewarding. It teaches the viewer, much like the animals teach Gauche, the value of slowing down and truly listening.

Echoes of Miyazawa

The film beautifully captures the spirit of Kenji Miyazawa's writing – its deep connection to nature, its gentle Buddhist undertones of interconnectedness, and its faith in the transformative power of art and empathy. The animals aren't just cute plot devices; they represent aspects of the natural world offering wisdom, challenging Gauche to look beyond his own frustrations and connect with something larger than himself. The final performance of the Pastoral Symphony isn't just technically proficient; it's imbued with the understanding and feeling he gained through his encounters. It's a subtle, profound message delivered without fanfare.

A Quiet Gem Unearthed

Gauche the Cellist might not have the epic scope or dazzling visuals of later Ghibli productions, but its quiet charm and heartfelt story make it an essential piece of animation history and a genuine treasure from the VHS era. It’s a film about perseverance, the unexpected ways we learn and grow, and the profound connection between humanity, nature, and art. It reminds us that mastery often comes not from solitary striving, but from engagement with the world around us, even in its most peculiar forms. Finding this tape felt like discovering a secret, a gentle melody amidst the louder sounds of the 80s rental shelves.

Rating: 8/10 This score reflects the film's beautiful, hand-crafted animation, its touching and deceptively simple story rooted in Miyazawa's profound worldview, and its significance as an early showcase of Isao Takahata's unique directorial vision. Its deliberate, gentle pacing might not resonate with everyone today, but for those willing to slow down, it offers a deeply rewarding and moving experience that perfectly justifies its rating.