Okay, fellow tapeheads, gather 'round the glow of the metaphorical CRT. While our beloved shelves at "VHS Heaven" are often stacked high with explosive action flicks, goofy comedies, and spine-tingling slashers, sometimes a different kind of magic found its way onto our screens. Today, we’re dimming the lights for something quieter, shorter, but no less impactful: Chris Wedge's stunning 1998 animated short, Bunny. This wasn't likely the tape you grabbed every Friday night, maybe not even one you rented intentionally. Perhaps you stumbled upon it, tucked away on an animation compilation or caught it during a late-night broadcast – a seven-minute gem that glowed with unexpected beauty and melancholy.

Bunny arrived just as computer animation was flexing its muscles beyond flashy logos and rudimentary shapes, hinting at the emotive power the medium could wield. It wasn't just technically impressive; it was art. And winning the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film in 1999 certainly cemented its place in animation history, didn't it?

### An Old Bunny and a Bothersome Moth

The premise is deceptively simple: we meet Bunny, a grumpy, elderly rabbit living alone in her rustic kitchen. Her quiet evening is disrupted by a persistent moth, flitting around her lone lightbulb. What begins as annoyance escalates into a comical, then slightly desperate, battle between the aging lagomorph and the determined insect. Director and writer Chris Wedge, who would later co-found the powerhouse animation studio Blue Sky Studios (yes, the folks behind Ice Age!), crafts a world that feels tangible, lived-in. You can almost smell the old wood of the cabin, feel the cool night air drifting through the window.

Bunny herself is a masterpiece of subtle character animation. Her movements are slow, deliberate, tinged with the weariness of age. Her mounting frustration with the moth feels utterly believable, shifting from swats with a wooden spoon to more elaborate, almost slapstick, attempts to quell the intrusion. Yet, beneath the cantankerous exterior, Wedge hints at a deeper loneliness, a life lived and winding down.

### The Glow of Radiosity

What truly set Bunny apart in 1998, and still looks remarkable today, was its pioneering use of radiosity rendering. Now, stick with me, tech fans – this wasn't just about making things look shiny. Radiosity simulates how light actually bounces off surfaces in the real world, creating incredibly soft, naturalistic lighting and subtle colour bleeding. It's why Bunny's fur looks so touchably soft, why the light filtering through the window feels so warm and atmospheric, why the shadows have such depth.

This complex technique, computationally very expensive at the time, was implemented using Blue Sky's proprietary CGI Studio software. It gave Bunny a painterly quality, a warmth that stood in stark contrast to the often colder, harder look of other early CGI. Chris Wedge and his small team pushed the boundaries, demonstrating that computer animation could evoke mood and emotion through light and texture, not just character movement. It was a gamble that paid off, creating visuals that felt less like computer graphics and more like a living illustration. This technical achievement wasn't just window dressing; it was integral to the film's poignant atmosphere.

### Waits, Wings, and Wonder

Adding immeasurably to the short's unique, bittersweet flavour is the soundtrack. The main piece is Tom Waits' "Shuffle Off to Buffalo" (originally from his 1993 collaboration with Robert Wilson and William S. Burroughs, The Black Rider). Waits' gravelly voice and the song's melancholic, slightly surreal carnival feel are a perfect, if unexpected, match for the visuals. It underscores the blend of the mundane (an old bunny, a kitchen) and the mystical (what happens next).

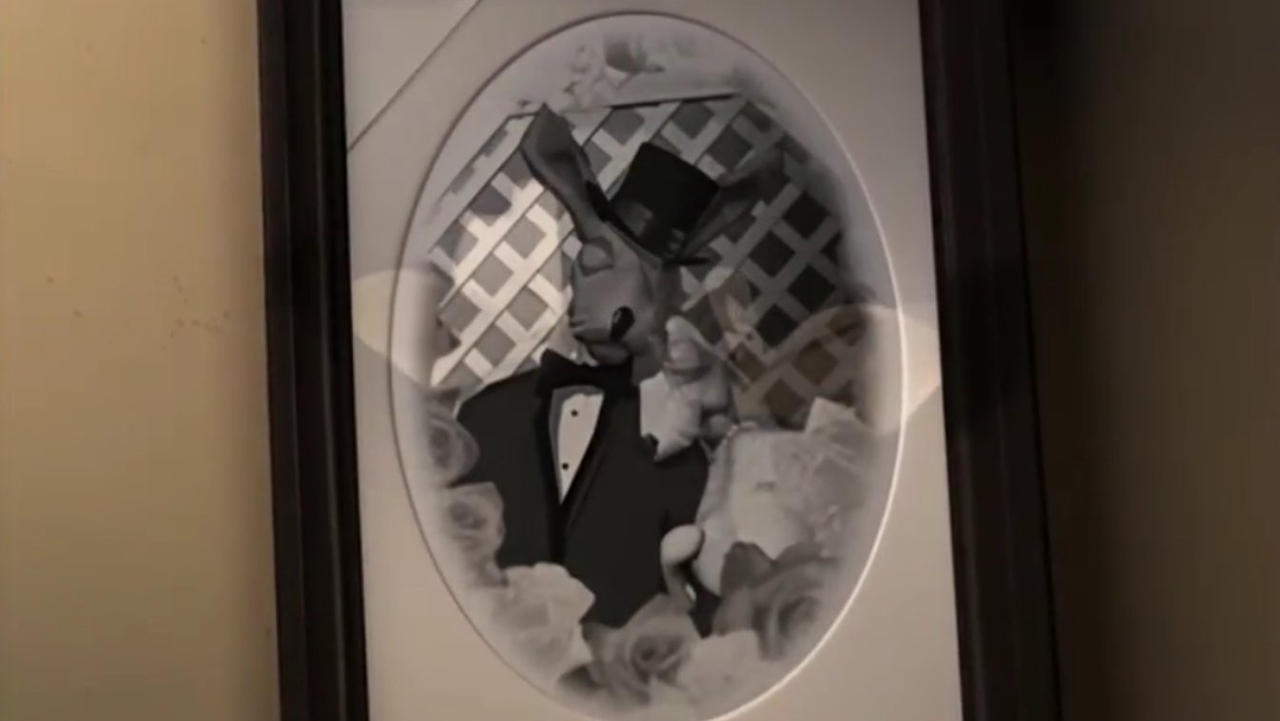

Spoiler Alert (Kind Of): The film culminates not in the simple demise of the moth, but in a moment of transcendence. As Bunny is drawn towards the light, she finds herself floating amidst countless moths, finally reuniting with her departed partner, towards a light resembling the cake seen in an old photograph. It’s a sequence that shifts the film from a quirky character study into something profoundly moving – a gentle meditation on aging, loss, and perhaps, letting go. The moth, initially an annoyance, becomes a guide, a catalyst for a final journey.

### From Short Wonder to Feature Powerhouse

Bunny's success, particularly its Oscar win, was a watershed moment for Chris Wedge and Blue Sky Studios. It proved their artistic vision and technical prowess, attracting the attention and investment needed to move into feature film production. Without the critical acclaim and visual benchmark set by Bunny, it's hard to imagine Scrat chasing that acorn quite so convincingly in Ice Age (2002) just a few years later. Bunny was the proof-of-concept, the beautiful calling card that announced a major new talent in animation had arrived. It demonstrated that compelling stories driven by character and emotion could be told with these new digital tools.

It may not have the bombast of a typical 80s/90s blockbuster, but Bunny represents another facet of that era's creative explosion: the pioneering spirit in digital art. Finding it felt like uncovering a secret, a quiet masterpiece that lingered long after the screen went dark. It reminds us that sometimes the smallest stories carry the biggest emotional weight.

VHS Heaven Rating: 9/10

This score reflects Bunny's groundbreaking technical achievement for its time, its stunning visual artistry that still holds up, its masterful use of music, and its deeply affecting, layered story told with minimal dialogue. It’s a near-perfect execution of a short film, losing perhaps only a point for not being the kind of repeatable, crowd-pleasing fare usually associated with peak VHS nostalgia, though its artistic merit within the era is undeniable.

Bunny is a poignant reminder from the late 90s that animation could be more than cartoons – it could be pure, luminous poetry flickering on the screen. A small film with a giant heart, and a moth that guides us somewhere beautiful.