The glare of streetlights reflecting off rain-slicked Chicago pavement. The hypnotic, pulsing synthesizers of Tangerine Dream scoring a meticulous, almost balletic act of violation. This isn't just how Thief begins; it's the film announcing its distinct identity from the first frame. Released in 1981, Michael Mann’s theatrical directorial debut felt like a jolt – a blast of neon-lit noir that was simultaneously hyper-realistic and achingly stylized. Watching it again now, decades after first sliding that well-worn cassette into the VCR, its power hasn't diminished; if anything, its stark portrayal of a professional trying to escape the life feels even more resonant.

### The Code of the Craftsman

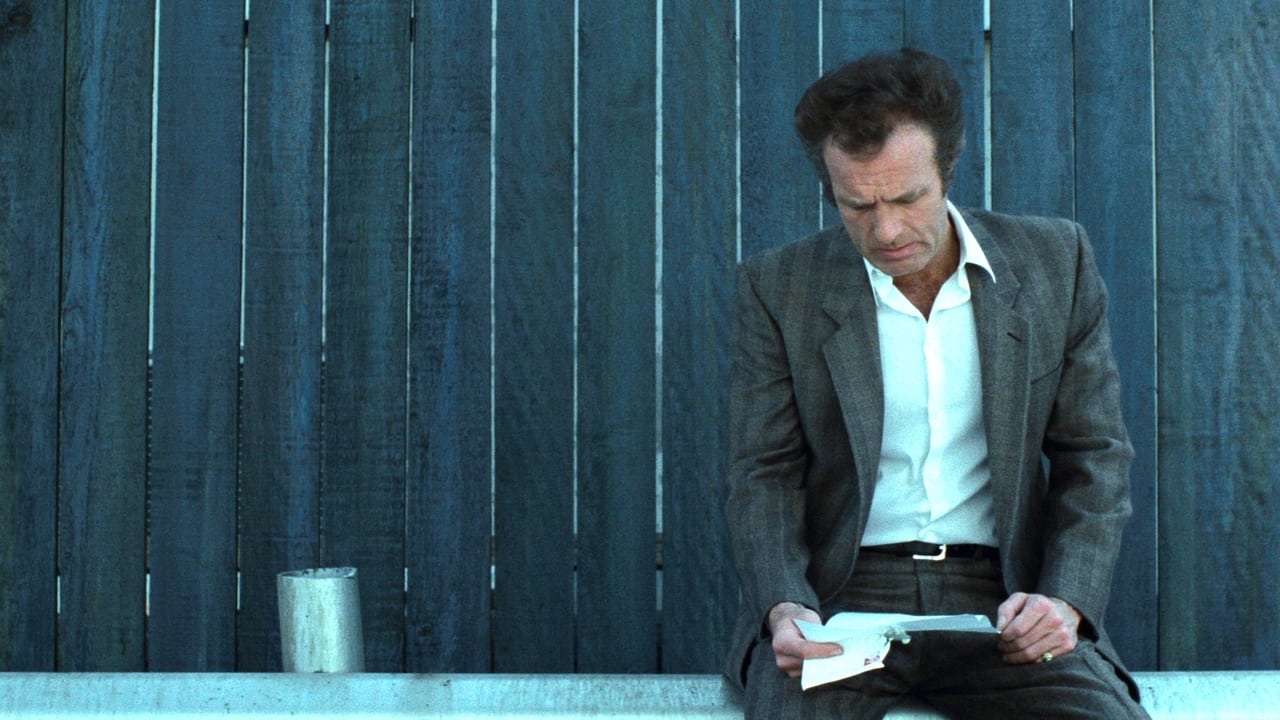

At the heart of Thief is Frank, portrayed with career-defining intensity by James Caan. Frank isn't just a safecracker; he's a master craftsman, an independent operator with a strict code and a carefully constructed plan for a future outside the criminal underworld. Caan embodies this duality perfectly. There's the coiled physical presence, the confidence born of expertise, visible in the way he handles his specialized tools – tools researched and built with obsessive authenticity under Mann's demanding eye. It’s said that Mann hired real-life thieves, like John Santucci (who plays Sgt. Urizzi), as consultants and even actors to ensure every detail, from the slang to the techniques, rang true. You feel that dedication on screen; the safe-cracking scenes aren't just plot points, they are procedural masterpieces, tense and utterly convincing.

But beneath the hardened exterior, Caan reveals Frank's deep-seated vulnerability, his desperate yearning for the normalcy he meticulously maps out on a postcard collage – the wife, the kid, the legitimate business. His scenes with Tuesday Weld as Jessie, the world-weary waitress who cautiously agrees to share his dream, are imbued with a fragile tenderness. Their diner conversation, where Frank lays bare his prison past and his meticulously planned future, is a masterclass in understated emotion. It’s raw, honest, and avoids the usual Hollywood sentimentality. Weld matches Caan note for note, her performance quiet but powerful, conveying a history of disappointment that makes her hesitant investment in Frank’s vision all the more poignant.

### Neon Jungle, Concrete Cage

Mann, even this early in his career (though already seasoned from TV work like The Jericho Mile), demonstrates the stylistic signatures that would define his filmography – the cool blue and steely grey color palette, the expressive use of urban landscapes, the immersive sound design. Chicago isn't just a backdrop; it's a character in itself. The cinematography by Donald E. Thorin captures the city's nighttime allure and its industrial grime, turning rain-swept streets and lonely highways into canvases of existential isolation. You can almost smell the damp concrete and exhaust fumes.

This visual poetry is amplified immeasurably by Tangerine Dream's iconic score. It’s hard to overstate its impact. The electronic pulses and atmospheric washes aren't just accompaniment; they are the film's heartbeat, driving the tension during the heists and underscoring Frank's internal turmoil. It was a bold choice in 1981, moving away from traditional orchestral scores, and it cemented Thief's place as a pioneer of the 80s synth-score sound, influencing countless films and even video games that followed. Remember hearing that pulse thrumming through the speakers of a chunky CRT TV? It felt utterly modern, almost futuristic back then.

### The Illusion of Escape

Of course, Frank's carefully laid plans inevitably collide with the brutal realities of organized crime, personified by the chillingly paternalistic mob boss Leo, played with sinister charm by Robert Prosky. The film expertly dissects the illusion of independence within a criminal hierarchy. Leo offers Frank the big scores he needs to get out, but the price is Frank's autonomy, the very thing he values most. Even Willie Nelson, in a surprisingly effective piece of casting as Frank's mentor and friend Okla, represents a cautionary tale – a man resigned to the life, offering Frank grim wisdom from behind bars.

The escalating conflict forces Frank to confront the impossibility of his dream within the world he inhabits. Does betraying your professional code to achieve personal freedom ultimately destroy the very self you're trying to save? The film doesn't offer easy answers. Mann reportedly spent significant time ensuring the technical aspects of the heists were accurate, sometimes frustrating the crew with his demands for realism. One famous sequence involving a thermal lance burning through a safe reportedly took hours of meticulous setup for mere seconds of screen time, showcasing the dedication to authenticity that grounds the film's more stylized elements. This painstaking detail wasn't just for show; it reinforces Frank's identity as a meticulous professional, making his later, more chaotic actions feel like a profound shattering of his core self.

### Lasting Echoes

Thief wasn't a massive box office smash upon release (grossing around $11.5 million against a $5.5 million budget), but its influence has grown exponentially over time. It laid the groundwork for Mann's later explorations of professional obsession and existential loneliness in films like Heat (1995) and Collateral (2004). Its blend of gritty realism and high style defined a particular brand of cool, atmospheric crime thriller that still resonates. You can see its DNA in everything from Drive (2011) to modern television dramas.

It remains a visceral experience – tough, melancholic, and ultimately unforgettable. It’s a film about the precise, dangerous beauty of craft, the seductive allure of the score, and the crushing weight of inescapable fate. It reminds us that sometimes, the only way out is through the fire.

Rating: 9/10

This rating reflects Thief's mastery of mood, its technical precision, James Caan's towering central performance, and its influential style. While perhaps stark for some tastes, its focused intensity and authentic portrayal of its world make it a high point of early 80s cinema and a cornerstone of the neo-noir genre. What lingers most is the haunting realization that for some, the dream of a normal life is the most dangerous score of all.