There’s a certain kind of tension that hangs heavy in the air, thick and electric, just before a storm breaks. The Long Good Friday bottles that feeling, decanting it straight onto the screen. Released in 1980 but feeling like the dying embers of the 70s clashing head-on with the cut-throat ambition of the coming decade, this isn't just a gangster film; it's a brutal, brilliant snapshot of a London teetering on the edge of transformation, embodied entirely by one man’s ferocious dream.

Cockney Kingpin, Global Dreams

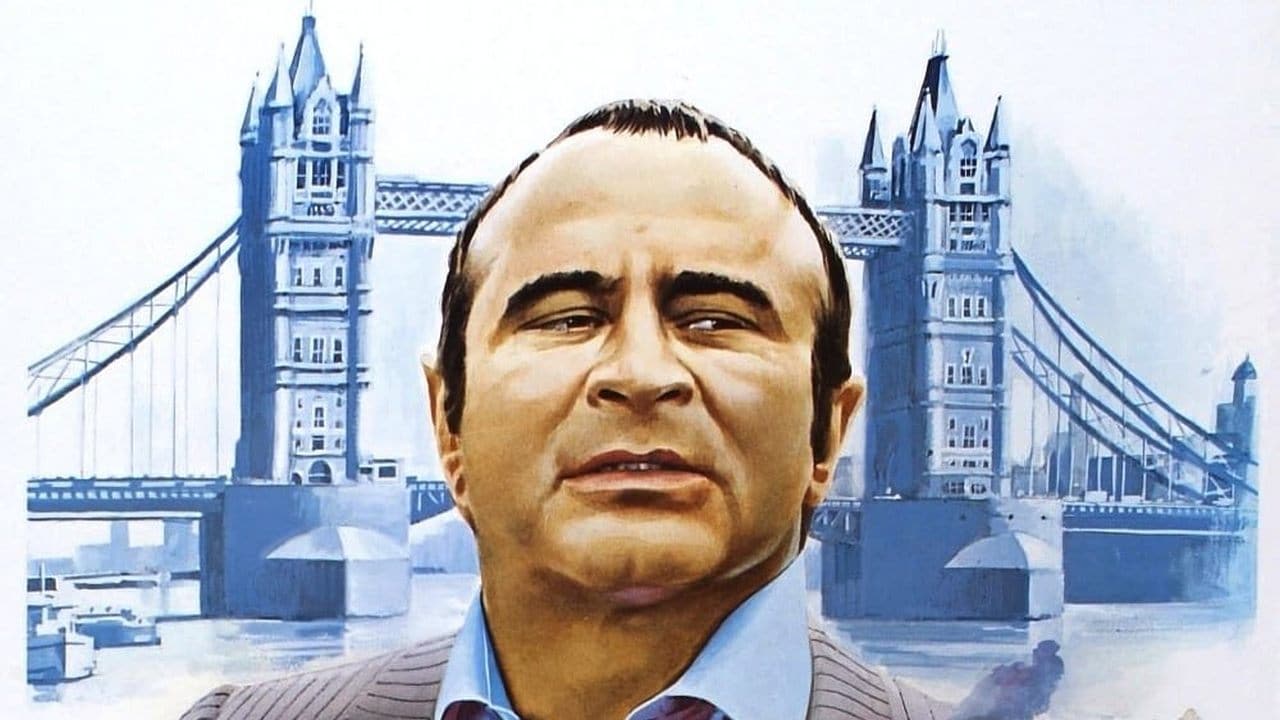

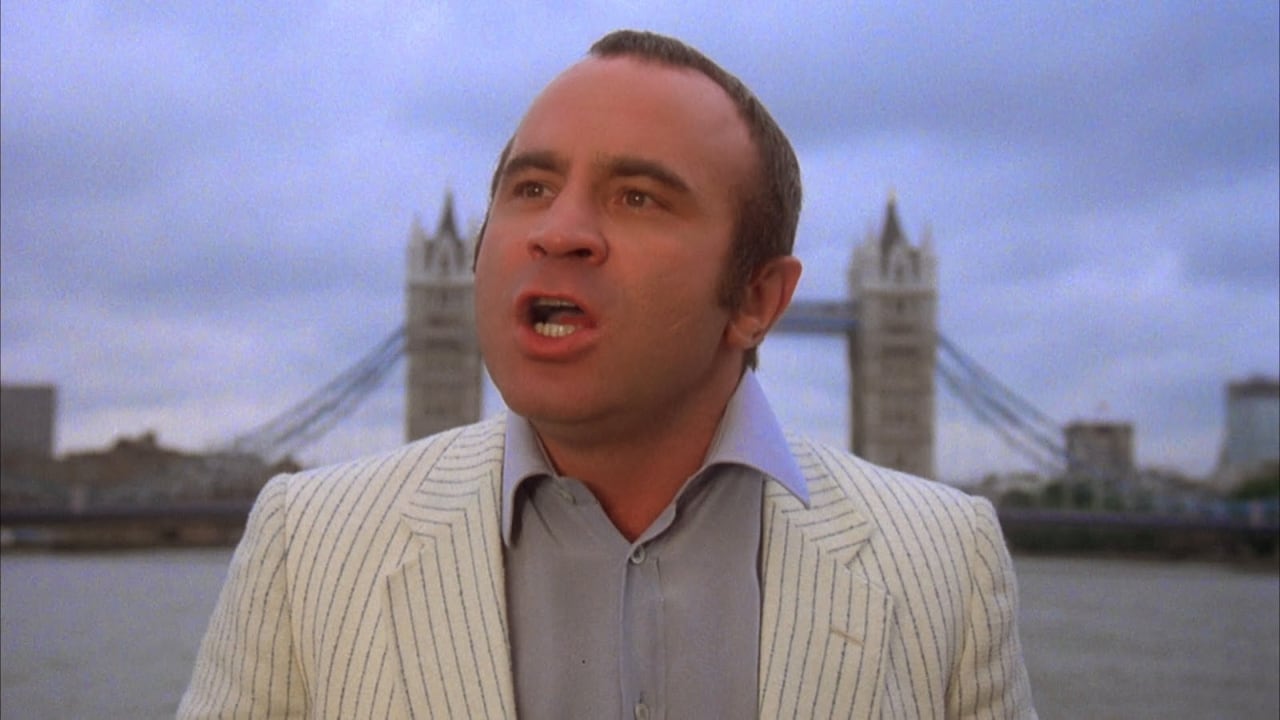

At the heart of this storm stands Harold Shand, brought to unforgettable life by the inimitable Bob Hoskins. Shand isn't your typical movie gangster. He’s sharp, ambitious, radiating a barely contained energy. He sees himself not merely as a crime boss, but as a legitimate businessman, poised to partner with the American Mafia to transform London's derelict Docklands into a glittering hub for the upcoming Olympics. He speaks of legacy, of civic pride, even as his empire is built on intimidation and violence. Watching him hold court on his yacht, the Thames stretching out before him like a kingdom waiting to be fully claimed, you almost believe him. It’s a performance etched in granite; Hoskins, who famously spent time observing London underworld figures (perhaps even the notorious Kray twins, depending on which story you hear) to prepare, doesn't just play Shand, he is Shand – the swagger, the sudden shifts from avuncular charm to terrifying rage, the vulnerability peeking through the cracks as his perfect Easter weekend begins to unravel. It's the role that rightly catapulted him to international stardom, paving the way for later triumphs like Mona Lisa (1986) and Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988).

A Partnership in Power and Peril

Beside Harold, radiating poise and intelligence, is Victoria, played with cool precision by Helen Mirren. Decades before she became cinematic royalty, Mirren shows us exactly why she was destined for greatness. Victoria is no mere accessory. She's Harold's partner, his confidante, handling diplomats and smoothing ruffled feathers with effortless grace. She understands the game, perhaps even better than Harold at times. Watch her face during the crucial dinner scene with the Americans; the subtle calculations, the supportive smiles masking a keen awareness of the stakes. Her journey through the film, from sophisticated hostess to a woman confronting the horrifying reality of Harold’s world, is quietly devastating. Their relationship feels authentic – a genuine partnership built on shared ambition and, yes, affection, making the eventual breakdown all the more potent.

London Calling: Trouble on the Line

Director John Mackenzie, working from a razor-sharp script by Barrie Keeffe, masterfully builds the tension. What starts as a series of seemingly isolated, violent incidents – a car bomb here, a murder there – slowly escalates, disrupting Harold's meticulously planned weekend showcase for his potential investors. The film excels at portraying the confusion, the paranoia, as Harold desperately tries to identify the unseen enemy striking at the heart of his operation. Who dares challenge him on his own turf, and why now? Mackenzie crafts a palpable sense of place; the film breathes the London air of the era – the greasy spoon cafes, the smoky pubs, the vast, empty Docklands promising fortunes or ruin. It’s gritty, unflinching, and feels utterly real. This realism might explain some of the initial nervousness from distributors; the film, completed in 1979, faced a delayed release until late 1980 (UK) / 1981 (US) partly because original backers ITC Entertainment got cold feet, worried about the film's violence and, significantly, its handling of the IRA subplot, fearing it was too sympathetic or inflammatory. Thankfully, producer John Daly's Hemdale Film Corporation stepped in, ensuring this masterpiece wasn't buried.

Echoes in the Music and the Mayhem

Adding immeasurably to the atmosphere is Francis Monkman's score. That pulsing, synthesized main theme is pure 80s dread, a relentless heartbeat driving the narrative forward, perfectly capturing the fusion of slick modernity and primal violence that defines Harold's world. And keep an eye out for a fresh-faced Pierce Brosnan in his film debut, making a chillingly effective appearance as a silent, watchful IRA operative – a small role, but one that leaves a distinct impression. The violence, when it comes, is shocking and brutal, never gratuitous. It serves the story, illustrating the bloody foundations upon which Harold’s dreams are built and the swift, merciless consequences of underestimating your enemies.

The Price of Ambition

The Long Good Friday is more than just a gripping thriller. It delves into themes of loyalty, betrayal, the corrosive nature of power, and the collision of old-world tribalism with new-world capitalism. Harold’s fatal flaw isn't just his ruthlessness, but his inability to see beyond his own sphere of influence, to understand the deeper, more potent forces stirring beneath the surface – forces represented by the ghost-like efficiency of the IRA seeking retribution. The film captures a specific moment in British history, the Thatcherite drive for enterprise brushing up against entrenched, violent traditions. Does Harold’s ambition blind him to the savage realities he cannot control?

The film’s relatively modest budget (reportedly around £930,000, or roughly $2.1 million then) is invisible on screen, a testament to Mackenzie’s taut direction and the commitment of the cast and crew. It feels expansive, important, delivering a story with weight and consequence. I still remember the distinct feel of the Thorn EMI rental tape, the grainy picture on the old CRT somehow enhancing the film's gritty texture. It felt dangerous, adult, a far cry from the glossy blockbusters also lining the shelves.

Rating: 9/10

This rating reflects the film's sheer power, driven by Hoskins' towering performance, Mirren's intelligent counterpoint, Mackenzie's assured direction, and a script that crackles with tension and insight. It loses perhaps a single point only for the fact that its specific political context might require a slight historical adjustment for some viewers today, but its core themes of ambition, power, and retribution remain timeless. The Long Good Friday isn't just one of the best British gangster films ever made; it’s a potent character study and a searing piece of social commentary that grabs you by the throat from the first frame and lingers long after the devastating final moments fade to black. What does Harold Shand truly see in those final seconds? Perhaps a reflection of the brutal world he tried, and failed, to master.