The salt spray hangs heavy in Potter's Bluff, clinging like a shroud. It’s a town postcard-perfect, deceptively serene, the kind of place where everyone knows your name… and perhaps, your fate. But beneath the quaint facade, something deeply wrong festers, a creeping dread that sinks into your bones long before the credits roll on Gary Sherman’s chilling 1981 masterpiece, Dead & Buried. This isn't just another early 80s shocker; it's a slow, methodical descent into seaside paranoia, the kind of film that felt genuinely dangerous tucked away on the horror shelf at the local video store.

### Welcome to Potter's Bluff. Population: Decreasing?

The setup hooks you with brutal efficiency. A photographer visiting the idyllic coastal town is set upon by a seemingly welcoming group of locals, only to be savagely beaten and burned alive. Sheriff Dan Gillis (James Farentino) investigates, but the horror only escalates as more visitors meet gruesome ends, orchestrated by smiling, ordinary townsfolk. The true nightmare begins when the victims… reappear. Walking, talking, unnervingly present. Farentino, perhaps best known to genre fans from TV fare like The Final Countdown (1980), perfectly embodies the mounting bewilderment and terror of a man whose reality is crumbling around him. He’s the anchor in a sea of inexplicable dread.

### Atmosphere Thicker Than Fog

What sets Dead & Buried apart is its unwavering commitment to atmosphere. Sherman, who would later give us the slicker but still effective Poltergeist III (1988), crafts a palpable sense of unease. The fog-drenched Northern California locations (Mendocino standing in for Potter's Bluff) feel isolated and claustrophobic, enhancing the feeling that there's no escape. The score by Joe Renzetti (Child's Play, 1988) is less about jump scares and more about a persistent, low-level thrum of wrongness that crawls under your skin. It’s the kind of patient, deliberate filmmaking that prioritizes mood over cheap shocks, building tension brick by unsettling brick.

### The Art of Mortality, Courtesy of Dobbs and Winston

Central to the town's morbid secret is the eccentric mortician, William G. Dobbs, played with unnerving glee by the legendary Jack Albertson (Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, 1971) in his final film role. Albertson reportedly embraced the role, even contributing lines, lending Dobbs a grandfatherly charm that makes his macabre profession all the more unsettling. His mortuary isn't just a place of rest; it's a workshop. And the tools of his trade? Well, that brings us to the film's most infamous element: the groundbreaking (and stomach-churning) practical effects spearheaded by a young Stan Winston, years before The Terminator or Jurassic Park.

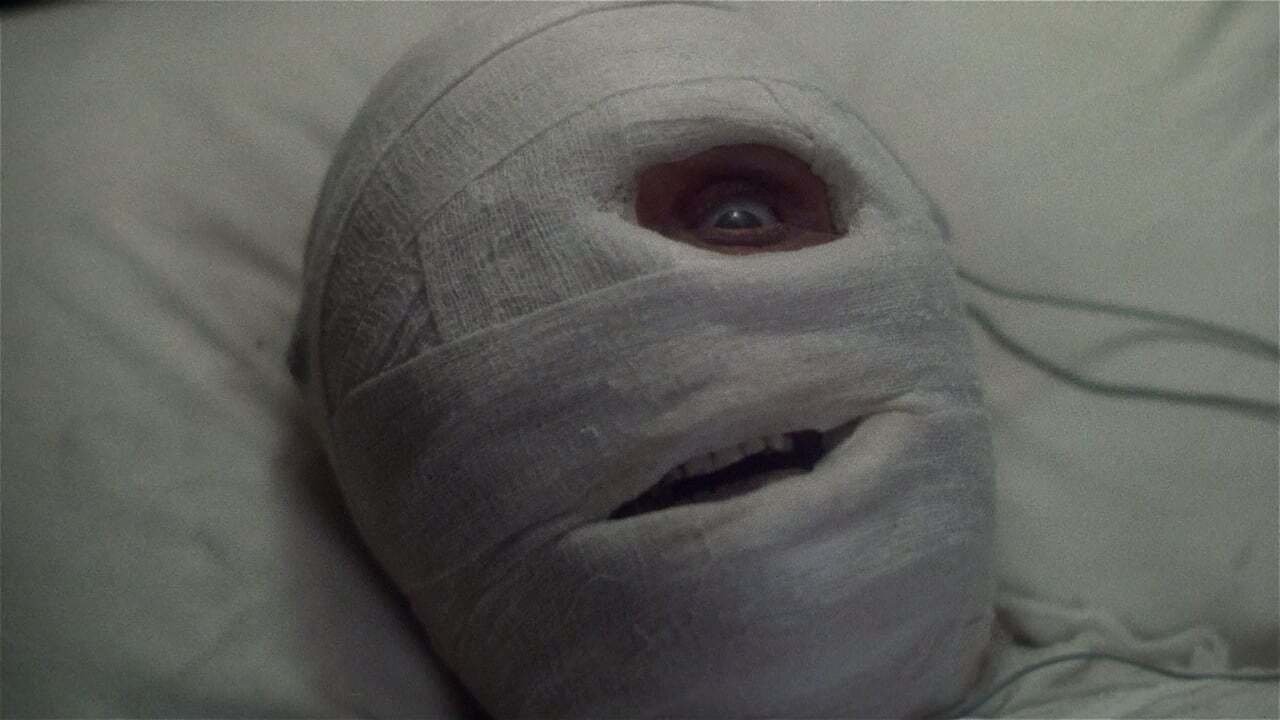

The screenplay, penned by Dan O'Bannon and Ronald Shusett – the minds behind Alien (1979) – allegedly underwent significant rewrites, shifting from a darker, almost comedic tone to the straight horror we see today. But O'Bannon's fascination with bodily violation clearly remained. Winston's work here is raw, visceral, and utterly convincing for its time. Remember the hypodermic needle scene? Or the ghastly facial reconstruction? These weren't CGI gloss-overs; they were painstakingly crafted illusions using latex, makeup, and ingenuity, possessing a tactile horror that often feels lost today. Winston himself considered the effects some of his most realistic, pushing the boundaries of what could be shown on screen and contributing significantly to the film's eventual notoriety, including landing it on the UK's infamous "Video Nasty" list for a time.

### A Disturbing Legacy

The film cleverly plays with the burgeoning slasher tropes of the era but subverts them. The killers aren't masked maniacs; they're your neighbours, the friendly faces you see every day. This communal evil adds a layer of psychological horror that resonates far more deeply. Melody Anderson (Flash Gordon, 1980) as Sheriff Gillis's wife, Janet, navigates this treacherous landscape, her role becoming increasingly pivotal as the town's secrets unravel. (Spoiler Alert!) The final twist, revealing the true nature of Potter's Bluff and Gillis's unwitting complicity, is a gut punch. It doesn't just explain the horror; it cements the feeling of inescapable doom. Didn't that revelation leave you reeling back in the day?

Dead & Buried wasn't a massive box office smash (grossing around $825,000 on a roughly $3 million budget), but its disturbing imagery and pervasive dread earned it a fervent cult following on VHS. It's a film that lingers, like the damp sea air of Potter's Bluff itself. It might feel slower-paced compared to modern horror, but its power lies in that deliberate unraveling, the mounting paranoia, and the sheer audacity of its practical gore effects.

VHS Heaven Rating: 8.5/10

Justification: Dead & Buried earns its high marks for its masterful atmosphere, genuinely unsettling premise, and Albertson's chilling final performance. Stan Winston's groundbreaking practical effects are a gruesome highlight, feeling shockingly real even decades later. While the pacing might test some modern viewers, the slow-burn dread and impactful twist deliver a unique and memorable slice of early 80s horror that stands apart from its slasher contemporaries.

It remains a potent piece of seaside gothic, a film that understands that sometimes the most terrifying monsters are the ones hiding behind a friendly smile in a town that looks just a little too perfect. A true gem for connoisseurs of creeping dread.