The static hiss fades, the tracking lines wobble for a moment, and then… that title card. Absurd. Sometimes Rosso Sangue. Sometimes even Anthropophagus 2, though the connection is tenuous at best. Whatever name graced the worn cardboard sleeve of the tape you nervously slid into the VCR, you knew you were in for something… different. This wasn't your standard Hollywood fare. This was Italian horror, unfiltered, unrelenting, and carrying the faint, thrilling scent of forbidden fruit, especially if you grew up hearing whispers of the infamous 'Video Nasties' list.

### The Unrelenting Storm

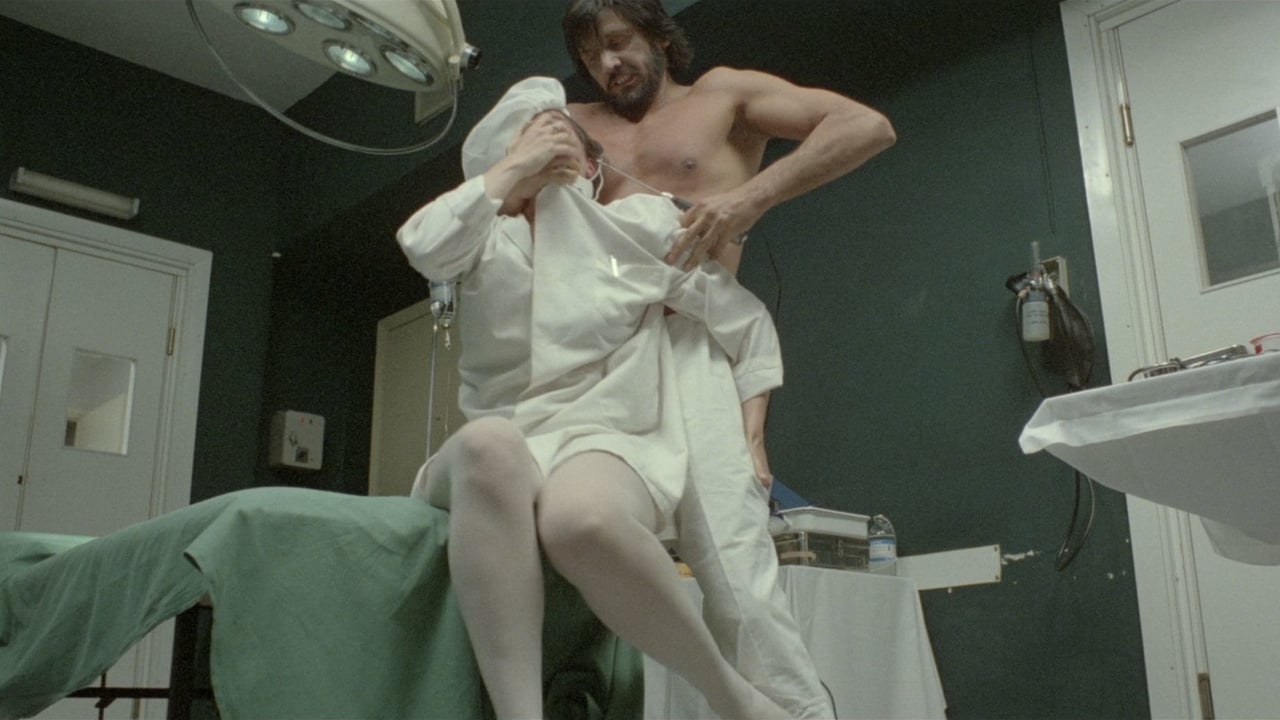

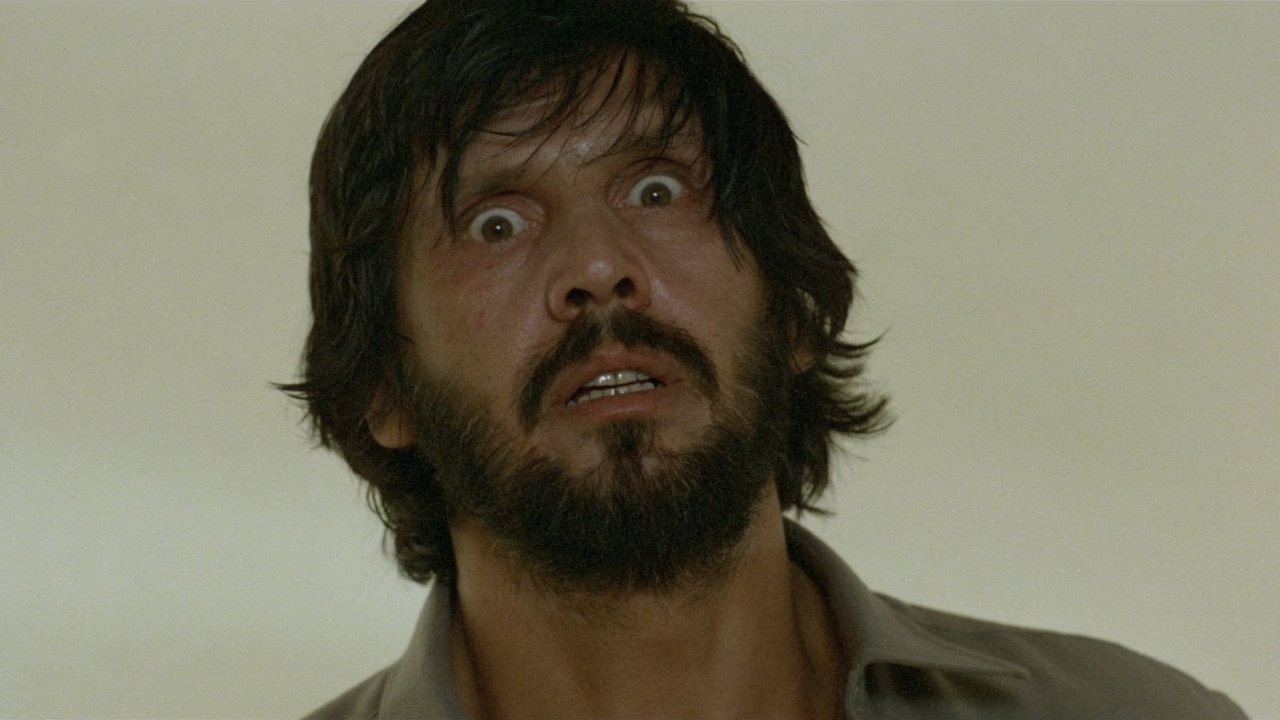

From the outset, Absurd establishes its singular, brutal focus. We're thrown into a frantic chase: a priest desperately pursuing a hulking figure through darkened woods. This figure, Mikos Stenopolis, played with terrifying physicality by the imposing George Eastman (who also co-wrote under his real name, Luigi Montefiori), isn't just a man; he's a force of nature gone horribly wrong. A freak scientific experiment has gifted him – or cursed him – with rapid cellular regeneration. Stab him, shoot him, he just… keeps… coming. It’s a simple, primal fear tapped into here: the unstoppable pursuer, the boogeyman who defies logic and death itself. Eastman, a veteran of Italian genre cinema often seen in Spaghetti Westerns and Poliziotteschi, embodies this perfectly. His sheer size and haunted, intense eyes sell the threat far more effectively than any convoluted backstory ever could. There's a rumour that Eastman found the repetitive nature of the chase sequences draining, pushing director Joe D'Amato (the notorious Aristide Massaccesi, director of Anthropophagus (1980) and countless other exploitation flicks) to make each kill more elaborate to keep things interesting.

### A Symphony of Shock

Let's be blunt: Absurd lives and dies by its gore. D'Amato, never one for subtlety, seems determined to push the boundaries of what was acceptable, even in the wild world of early 80s horror. This isn't about slow-burn tension or psychological dread; it's about visceral, stomach-churning spectacle. The practical effects, while undoubtedly dated by today's standards, possess a raw, tangible quality that CGI often lacks. Remember watching these scenes on a fuzzy CRT, the lurid colours bleeding slightly? Didn't that somehow make the grue even more unsettling?

We get infamous moments that were whispered about in schoolyards and debated over scratched rental counter tops. The head meeting a bandsaw. The excruciating encounter with a drill press. The truly nasty oven scene involving poor Peggy (played by Cindy Leadbetter in an uncredited role according to some sources, though this remains debated among fans). D'Amato allegedly revelled in orchestrating these sequences, focusing his limited budget squarely on maximising the shock value. The effects team, working under immense pressure and with few resources, relied on butcher shop offal, latex, and gallons of Karo syrup blood, lending the violence a messy, almost tactile reality that stuck with you long after the tape ejected.

### Between the Bloodshed

When Mikos isn't creatively dispatching the unfortunate residents of this small American town (actually filmed, like many Italian horrors aping US settings, around Rome and environs), the film… ambles. The plot mechanics explaining Mikos's condition are vaguely waved at, involving genetic experiments and the Vatican (naturally). We follow the Bennett family – patriarch Mr. Bennett (Charles Borromel), his bedridden wife (Edmund Purdom makes a brief appearance as the priest!), and their children, including young Katia, played by Katya Berger, daughter of William Berger. Annie Belle (Laura), a frequent D'Amato collaborator, plays the babysitter unwittingly trapped in the house with the recuperating monster. While the performances are functional within the context of exploitation cinema, the characters often feel like placeholders waiting for Mikos's inevitable arrival. The score by Carlo Maria Cordio attempts to inject tension, but it often feels repetitive, lacking the iconic power of soundtracks from Carpenter or Goblin contemporaries.

The connection to Anthropophagus feels purely like a marketing gimmick slapped on by distributors eager to capitalize on the previous film's notoriety. While both star Eastman as a monstrous killer and were directed by D'Amato, the stories and characters are entirely separate. Absurd is less mythic, more of a relentless home invasion slasher amplified by the killer's regenerative abilities.

### Banned But Not Forgotten

Perhaps the most enduring part of Absurd's legacy, particularly for UK viewers, is its status as one of the most prominent 'Video Nasties'. Fully banned by the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) and successfully prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act, the film became a symbol of the moral panic surrounding home video in the early 80s. Its notoriety only fueled its cult status, making finding a copy feel like unearthing forbidden treasure. Did that illicit thrill enhance the viewing experience back then? For many, myself included, it absolutely did. Owning or even just seeing a film the authorities deemed too shocking felt like a small act of rebellion.

The film’s minuscule budget (estimated figures are hard to pin down but certainly sub-$1 million) stands in stark contrast to the cultural ripples it caused. It’s a testament to the power of graphic imagery and the allure of the forbidden, especially in an era before the internet made such content instantly accessible.

***

Absurd is undeniably crude, often clumsy in its storytelling, and padded between its moments of graphic horror. Yet, there's an undeniable, raw energy to it. It’s a pure, unadulterated slice of early 80s exploitation filmmaking, driven by George Eastman's terrifying presence and Joe D'Amato's gleeful dedication to shocking his audience. It doesn't aim for high art; it aims squarely for the gut, and largely succeeds on those terms.

Rating: 6/10

Justification: The score reflects the film's effectiveness as a notorious gore-fest and its historical significance as a 'Video Nasty', anchored by Eastman's imposing performance. However, it's docked points for its thin plot, often sluggish pacing between kills, and overall lack of polish compared to its slasher contemporaries. It delivers exactly what it promises – absurdity and graphic violence – making it a fascinating, if grisly, time capsule from the VHS shelves.

Final Thought: While time hasn't necessarily been kind to its narrative finesse, Absurd remains a potent example of how far exploitation cinema would go in the VHS boom years, leaving a bloody stain on the memory long after the screen goes dark.