It waits in the memory like a tarnished coin, heavy with rumour and whispered warnings. Not just a movie, but a dare. Caligula wasn't the kind of tape you casually grabbed from the 'New Releases' wall; it often lurked in the back, maybe behind a counter, its provocative cover art promising something far beyond the usual sword-and-sandal epic. Finding it, renting it, felt like an illicit act, a peek behind a curtain that perhaps should have remained drawn. The hum of the VCR pulling in that cassette seemed louder, charged with anticipation for something notorious, something fundamentally wrong.

Imperial Decay, Cinematic Chaos

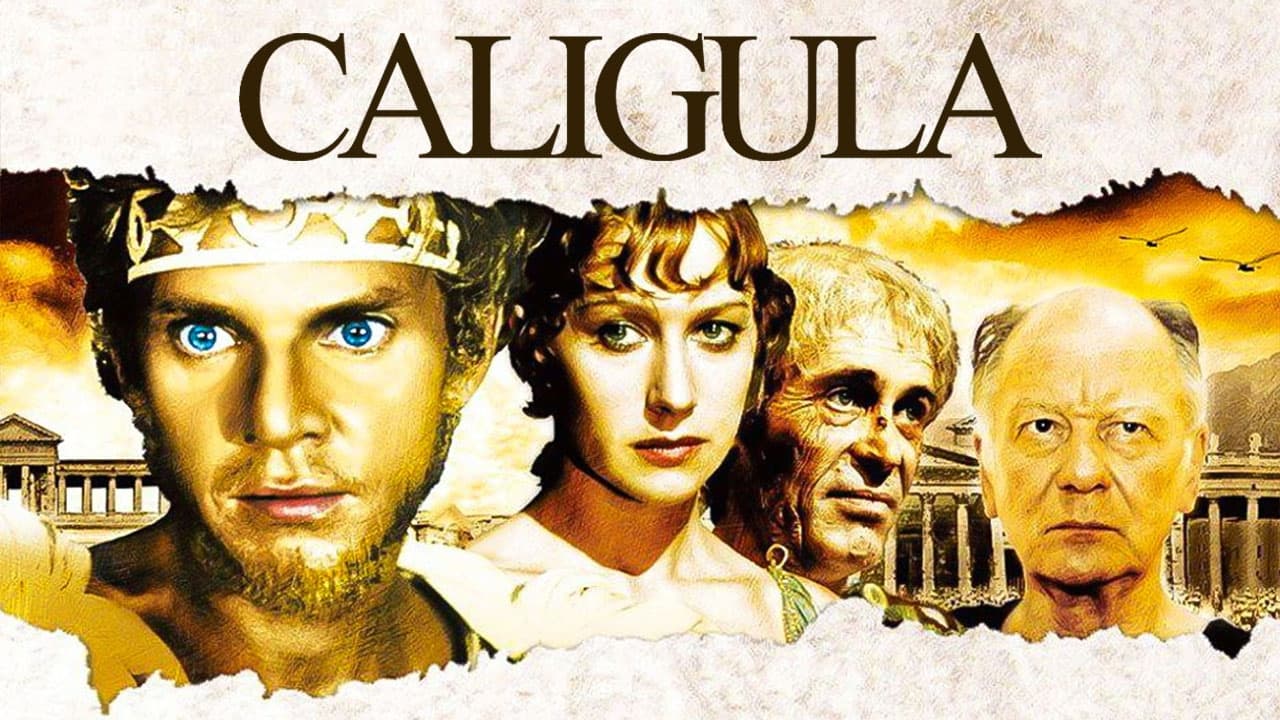

On paper, it sounds almost respectable: a historical epic penned by the esteemed Gore Vidal, charting the infamous reign of the Roman emperor Gaius Caesar Germanicus, nicknamed Caligula. It boasted a staggering cast, including Malcolm McDowell (still radiating the anarchic energy of A Clockwork Orange), the legendary Peter O'Toole and Sir John Gielgud, and a young, formidable Helen Mirren. The production design, masterminded by Danilo Donati (Fellini's frequent collaborator), is genuinely lavish, capturing a sense of decaying opulence, vast marble halls hinting at the moral rot within. The budget ballooned to a reported $17.5 million – an enormous sum for 1979 (roughly $74 million today), largely bankrolled by Penthouse magazine founder Bob Guccione. And there, the respectable veneer cracks wide open.

What unfolds is less a coherent historical drama and more a phantasmagoria of cruelty, sexual depravity, and bewildering excess. McDowell throws himself into the title role with a terrifying, almost gleeful abandon. His Caligula isn't just mad; he's a petulant, sadistic child wielding absolute power, his eyes burning with capricious malice. It’s a performance of startling intensity, often grotesque, sometimes magnetic, but utterly unrestrained. Doesn't his descent feel less like character development and more like an excuse for increasingly shocking set pieces?

A Battle Behind the Toga

The film's chaotic nature reflects its tortured production. Gore Vidal envisioned a sharp political satire about power corrupting absolutely. Director Tinto Brass aimed for a visually flamboyant, erotically charged art film exploring decadence. Guccione, however, saw an opportunity for something far more explicit. He notoriously filmed additional, hardcore pornographic scenes (without the principal actors' involvement, though look-alikes and some supporting cast were used) and inserted them into the final cut after firing Brass. This led Vidal to demand his name be removed (often credited as "Based on an original screenplay by Gore Vidal"), leaving behind a bizarre chimera – part historical epic, part art-house provocation, part explicit exploitation flick. The resulting film feels disjointed, lurching between moments of genuine craft (those sets, some hauntingly framed shots) and scenes of baffling crudeness. Remember the stories? Vidal reportedly quipped he wrote a historical drama, and they inserted hardcore scenes, turning his screenplay into the "world's most expensive screen wipe."

The presence of giants like O'Toole (as Tiberius) and Gielgud (as Nerva) lends a surreal gravity to the proceedings. Watching these titans of the stage navigate scenes adjacent to utter debauchery is an experience in itself. O'Toole, particularly, seems almost spectral, delivering his lines with weary gravitas amidst the gathering storm of Caligula's madness. Helen Mirren, as Caesonia, provides one of the film's few grounding elements, projecting intelligence and a chilling pragmatism even as she enables Caligula's worst impulses. Her commitment, even in this maelstrom, is undeniable.

More Than Just History, Less Than Art?

Stripped of its historical pretensions and artistic ambitions by the behind-the-scenes warfare and explicit additions, Caligula becomes something else entirely: a monument to bad taste, perhaps, but an undeniably memorable one. The violence is often shocking and brutal, the sex explicit and frequently non-consensual within the narrative, creating an atmosphere of pervasive unease. It’s designed to provoke, to repel, to fascinate in its sheer audacity. It's not "scary" in the horror sense, but its depiction of unchecked power and human cruelty leaves a distinctly cold feeling. Did anyone else find the giant, bladed execution machine genuinely unnerving, despite the surrounding chaos?

The practical effects, particularly the gore, have that specific late-70s grimy quality – less polished than later decades, but possessing a visceral, unpleasant weight. It aimed for shock value, and even filtered through decades and the desensitization of modern media, some moments retain their power to disturb, precisely because they feel so gratuitously cruel.

Enduring Infamy

Caligula is less a film to be enjoyed and more one to be experienced, perhaps endured. It’s a fascinating car crash – a collision of talent, ambition, ego, and exploitation. Watching it on VHS back in the day felt like accessing forbidden knowledge, a rite of passage for some cinephiles drawn to the extreme edges of cinema. It wasn't comfortable viewing then, and it certainly isn't now.

Rating: 3/10

Justification: This score reflects the film's status as a notorious curiosity rather than a successful piece of filmmaking. Points are awarded for the sheer scale, the committed (if unhinged) lead performance by McDowell, the presence of acting legends giving it their all amidst the chaos, and the genuinely impressive production design. However, it loses significant points for its narrative incoherence, tonal inconsistency, tedious stretches, and the exploitative nature of the Guccione-added content that fundamentally undermines any artistic or historical merit it might have aspired to. It's a failure, but a spectacular, unforgettable one.

Caligula remains a singular artifact – a testament to cinematic hubris and the strange, often murky waters where art, history, and exploitation collide. It wasn't heaven finding this on VHS, more like a deliberate descent into a uniquely Roman kind of hell, leaving you wondering not just about the madness on screen, but the madness behind its creation.