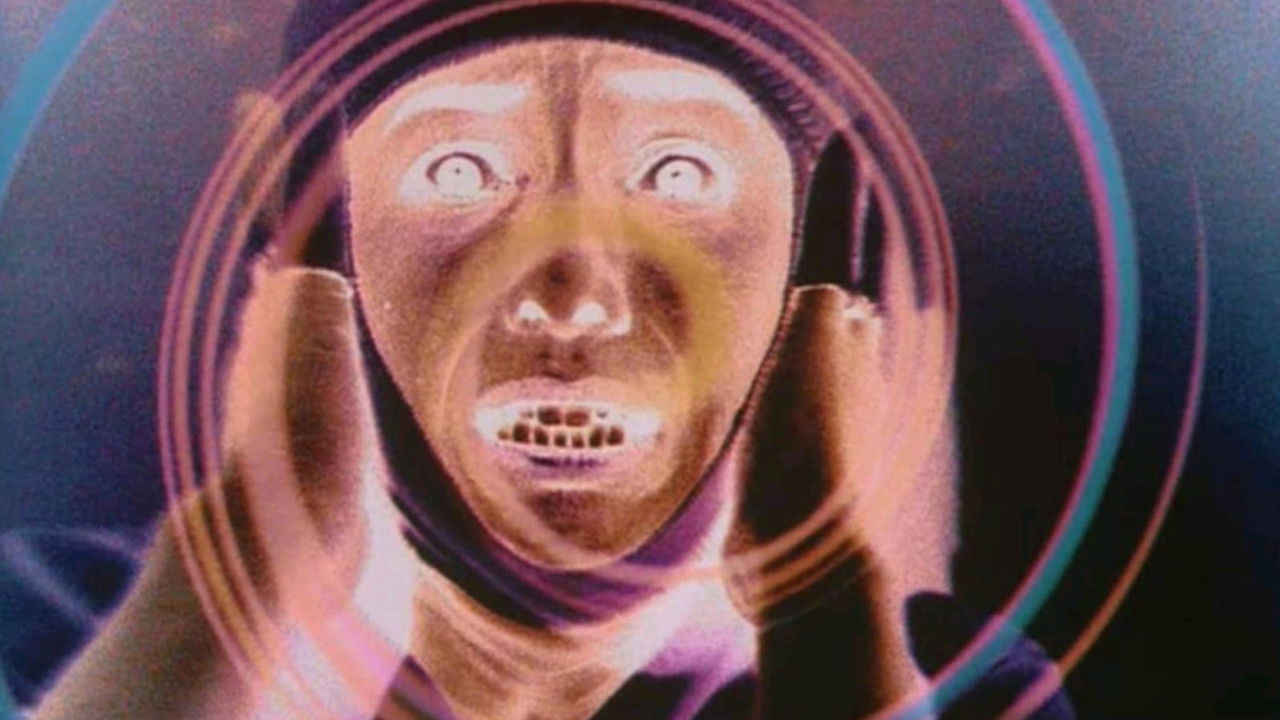

There's a peculiar nausea that Uzumaki (2000) induces, a feeling less like sharp fear and more like a slow, creeping vertigo. It’s the sensation that the very fabric of reality is warping, coiling in on itself, right there on your flickering CRT screen. Forget jump scares; this is the horror of the inevitable pattern, the cosmic dread found not in the dark, but in the relentless curve of a spiral. Watching it feels like succumbing to a low-grade fever dream, one that lingers unsettlingly long after the VCR clicks off.

Welcome to Kurouzu-cho

The seaside town of Kurouzu-cho seems ordinary enough at first glance, albeit draped in a perpetual, sickly green-grey filter that feels like mildew blooming on the film stock itself. But something is deeply wrong. High schooler Kirie Goshima (Eriko Hatsune) starts noticing it subtly – the way wind whips leaves into spirals, the patterns in ceramic bowls, the unsettling obsession her boyfriend Shuichi Saito’s (Fhi Fan) father develops with the shape. This isn't just eccentricity; it's a contagion, an infection of form spreading through the town's populace, twisting minds and bodies into grotesque parodies of the spiral motif. The plot unfolds less like a traditional narrative and more like a series of escalating vignettes of surreal horror, each one plumbing new depths of bizarre, pattern-based body horror.

A Visual Descent into Madness

Director Higuchinsky (a pseudonym for Akihiro Higuchi), bringing a sensibility perhaps honed in the world of music videos, drenches Uzumaki in a distinctive, almost hallucinatory visual style. The colour palette is oppressively desaturated, emphasizing greens and greys, making the occasional splash of red feel even more visceral. He translates the static, intricate horror of Junji Ito's original manga panels into moving images with a surprising degree of success, capturing the sheer wrongness of the transformations. Remember the infamous "snail boy" sequence? Or the chilling escalation of the classmate whose hair develops a malevolent life of its own? These moments, achieved through a blend of surprisingly effective practical effects and early, sometimes endearingly dated CGI, possess a unique power. They aren't always seamless, but their tangible, often Cronenbergian unease burrows under your skin in a way slicker modern effects often fail to. The low budget ($1.1 million approximately, a modest sum even then) arguably forced a creativity that enhances the film's grimy, unsettling aesthetic.

Spiraling Performances

Amidst the escalating madness, Eriko Hatsune provides a necessary anchor as Kirie. Her performance is one of growing unease and quiet determination, a relatable human center in a world dissolving into obsessive patterns. Opposite her, Fhi Fan as Shuichi captures the despair of someone who senses the town's curse more acutely, becoming increasingly withdrawn and paranoid. His quiet resignation ("The spiral... it's contaminated everything") feels chillingly believable. The supporting cast embraces the grotesque transformations with unnerving commitment – particularly the actors portraying the early victims of the spiral curse, whose descents into obsession are both pitiable and deeply disturbing. One can only imagine the on-set atmosphere trying to bring Ito's disturbing visions, like a man contorting himself into a washing machine tub, to life.

From Manga Page to Flickering Screen

Adapting Junji Ito's work is notoriously difficult; his power lies so much in the intricate detail and panel-by-panel reveals of his artwork. Uzumaki the film faced an additional hurdle: it was produced while the manga was still being published. This fascinating production constraint meant the filmmakers, including writers like Kengo Kaji and Takao Nitta, had to craft their own conclusion to the spiral epidemic before Ito had finished his own epic, sprawling ending. This leads to a finale that feels somewhat abrupt compared to the source material's grand, cosmic horror, focusing more on Kirie and Shuichi's fate. While some manga purists might balk, the film arguably succeeds on its own terms, capturing the essence of Ito's escalating dread and body horror, even if it truncates the narrative scope. It translates the feeling of reading Ito – that blend of morbid curiosity and profound revulsion – remarkably well for its time.

The Lingering Curse of the Spiral

Uzumaki arrived near the peak of the J-horror boom that washed over Western shores in the late 90s and early 2000s, films like Ringu (1998) and Ju-On: The Grudge (2002) finding audiences hungry for a different flavour of fear. Yet, Uzumaki stands apart. It’s less about ghosts and more about an abstract, environmental horror – a conceptual terror made flesh. Its influence might be less direct than its contemporaries, but its unique brand of surrealism and body horror certainly left an imprint on the landscape of weird cinema. Doesn't that central image, the spiral itself, still feel unnerving in its simplicity and ubiquity once the film plants the idea in your head? It’s a testament to the power of Ito’s original concept and Higuchinsky's distinctive interpretation. It’s a film that doesn’t just scare you; it makes the world feel slightly tilted, leaving you glancing warily at shells, ferns, and stirred coffee for days afterward.

---

VHS Heaven Rating: 7.5/10

Justification: Uzumaki earns its score through its incredibly potent atmosphere, unique visual style, and unforgettable sequences of surreal body horror that faithfully capture the spirit of Junji Ito's work. Its commitment to its bizarre central conceit is admirable. Points are slightly deducted for the sometimes-dated CGI and an ending constrained by the manga's ongoing publication, which feels less impactful than the source material's conclusion. However, its power to genuinely disturb and linger in the mind remains undeniable.

Final Thought: More than just a horror film, Uzumaki is an experience – a descent into obsessive patterns and visual weirdness that perfectly encapsulates the strange gems you could unearth in the video store's cult section. It’s a film that coils around your brain and refuses to let go.