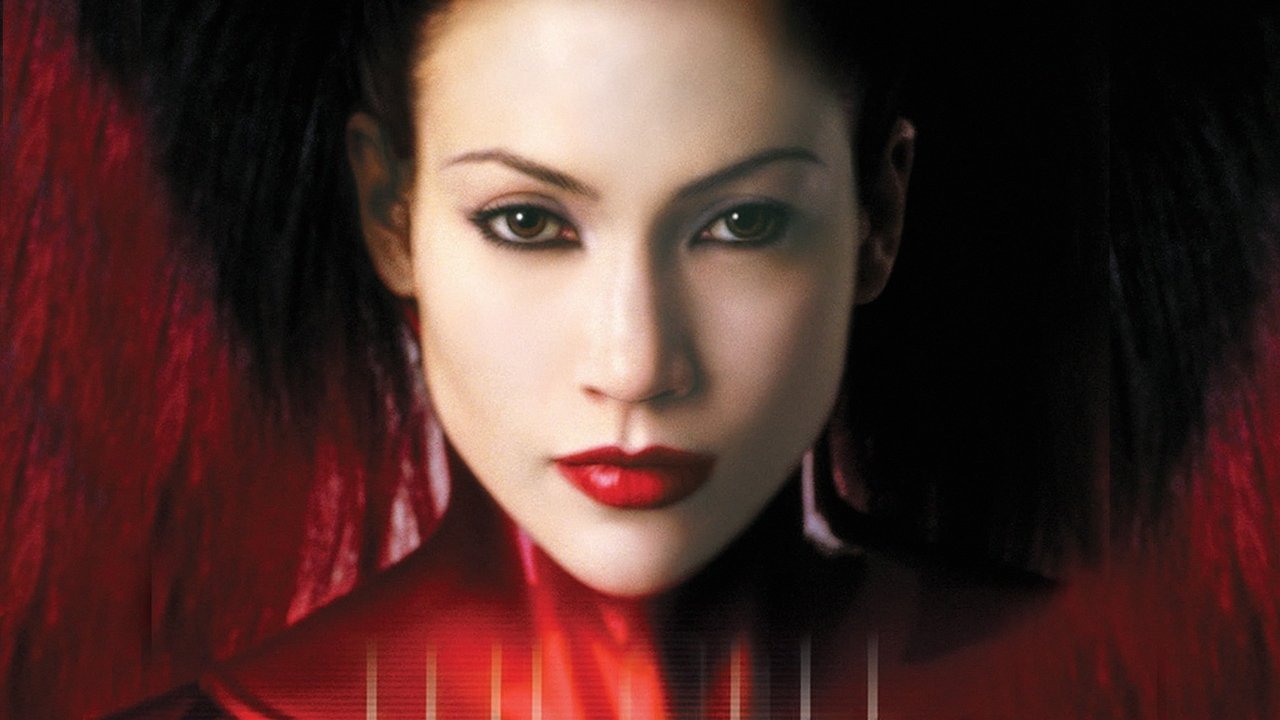

It begins not with a scream, but with a terrible beauty. A horse, segmented into glass-encased slices, still twitching with phantom life against an obsidian landscape. This single, unforgettable image from Tarsem Singh’s The Cell (2000) perfectly encapsulates the film’s modus operandi: seducing the eye with breathtaking artistry while simultaneously plunging the viewer into the deepest wells of human depravity. Arriving just as the millennium turned, The Cell felt like something darkly different, a visual feast served on a platter of pure nightmare fuel, a tape you might have hesitantly picked up at Blockbuster, drawn by the strange cover art, utterly unprepared for the trip inside.

A Mind is a Terrible Place to Visit

The premise itself is pure high-concept sci-fi horror. Catherine Deane (Jennifer Lopez, stepping into far darker territory than usual) is a child psychologist pioneering an experimental neurological technology. It allows her consciousness to literally enter the mind of a comatose patient, forming a psychic bridge to aid recovery. But when the FBI, led by Agent Peter Novak (Vince Vaughn, playing it surprisingly straight and weary), captures serial killer Carl Stargher (Vincent D'Onofrio) mere hours before his latest victim drowns in a remote, automated chamber, they face a desperate race against time. Stargher has fallen into an irreversible coma, his victim's location locked away inside his fractured psyche. Catherine's only choice: jack into the labyrinthine horrors of a killer's mind to find the girl before it's too late.

Painting with Nightmares

What follows is less a traditional thriller and more a descent into a surrealist hellscape. Director Tarsem Singh, previously known for his visually opulent music videos (like R.E.M.'s "Losing My Religion"), unleashes an astonishing torrent of imagery. Stargher's inner world isn't just dark; it's a meticulously crafted gallery of horrors, drawing inspiration from fine art masters like H.R. Giger, Damien Hirst, and Odd Nerdrum, alongside religious iconography twisted into grotesque forms. Remember those unsettlingly beautiful, yet deeply disturbing costumes designed by the legendary Eiko Ishioka? They weren't just clothes; they were manifestations of trauma, power, and pain made physical. Singh famously storyboarded the entire film himself, treating each frame like a baroque painting. The production design is the film’s undeniable star, creating landscapes that feel both alien and chillingly intimate – the vast, echoing chambers, the throne room where Stargher reigns as a demonic king, the waterlogged corridors reflecting a tortured past. The sheer audacity of the visuals, a blend of practical artistry and early, ambitious CGI, felt groundbreaking back then, didn't it? Even if some effects show their age, the design remains potent.

The King in His Prison

While the visuals stun, the film rests heavily on the shoulders of Vincent D'Onofrio. His portrayal of Carl Stargher is terrifying precisely because it finds flickers of wounded humanity within the monster. He embodies both the timid, abused child and the monstrous, self-proclaimed king who enacts ritualistic torture. D'Onofrio reportedly immersed himself deeply, exploring the psychological roots of such darkness, and it shows. He doesn't just play a killer; he inhabits a shattered mindscape. There are stories that D'Onofrio’s intensity on set was palpable, creating an atmosphere that genuinely unnerved some of the crew, particularly during the scenes depicting Stargher’s elaborate, S&M-inspired rituals. It's a performance that stays with you, uncomfortable and complex. Jennifer Lopez provides the empathetic anchor, her journey into Stargher’s mind mirroring the audience’s own descent, while Vince Vaughn offers a grounded counterpoint to the escalating surreality, though his character perhaps feels the most conventional within this wildly unconventional film.

Beauty and Brutality

The Cell wasn't universally embraced upon release. Its narrative can feel secondary to the visual spectacle, and some critics found the blend of high art aesthetics and brutal violence jarring, even exploitative. Made for a reported $33 million, it performed decently, pulling in over $100 million worldwide, suggesting audiences were intrigued by its unique brand of psychological horror. Yet, it remains a divisive film. Is it a profound exploration of trauma reflected through art, or merely a series of shocking images strung together? Perhaps it's both. The film doesn't flinch from the ugliness of Stargher's crimes, using its visual poetry not to soften the blow, but to explore the twisted origins of his pathology. That scene involving the horse – apparently achieved through meticulous practical effects and careful editing, causing much PETA concern despite assurances of animal safety – is still potent imagery. The film’s power lies in this uncomfortable juxtaposition: the sheer aesthetic beauty used to depict utter psychological horror.

Legacy of a Dark Dream

Watching The Cell today, perhaps on a streaming service instead of a worn-out VHS, its ambition remains striking. It dared to prioritize visual storytelling and psychological depth over conventional plotting in a way few mainstream thrillers did at the time. It pushed boundaries, not just in its graphic content (original cuts were reportedly even more intense, requiring trims to avoid an NC-17 rating), but in its artistic aspirations. It feels like a film born from the dark glamour and anxieties of the late 90s, stepping boldly, if disturbingly, into the new millennium. While its direct influence might be debated, its commitment to creating a unique, immersive, and deeply unsettling mental landscape earns it a distinct place in the pantheon of psychological horror. It's a film that aims to get under your skin through imagery, not just jump scares, leaving lingering echoes of its terrible beauty.

Rating: 8/10

The Cell earns its high marks for sheer visual audacity, Vincent D'Onofrio's towering performance, and its unforgettable, art-infused nightmare logic. It loses a couple of points for a narrative that occasionally feels overshadowed by the spectacle and character arcs that could have been deeper outside of Stargher's mind. Still, as a piece of uniquely disturbing cinema from the turn of the millennium, it remains a potent and visually unparalleled experience. A dark dream committed to film, beautiful and utterly terrifying.