Before the hum of the dial-up modem became a household symphony, before the internet truly wove itself into the fabric of everyday life, there lingered a nascent, buzzing anxiety. What if the growing network connecting our world wasn't just wires and code? What if something malevolent could slip through the digital cracks? 1993's Ghost in the Machine plugs directly into that specific early-90s techno-paranoia, delivering a jolt of fear that felt chillingly plausible amidst the beige boxes and flickering CRT screens of the era.

### The Spark of Terror

The setup is brutally efficient, almost mundane in its horror. A serial killer known as the "Address Book Killer," Karl Hochman (Ted Marcoux), obtains the address book of Terry Munroe (Karen Allen) after a freak accident during a thunderstorm merges his dying consciousness with the electrical grid and interconnected computer networks. Suddenly, the killer isn't just out there; he's in there – lurking in the phone lines, the power grid, the primitive networked appliances that were just starting to fill suburban homes. It’s a terrifyingly intimate invasion, transforming everyday technology into potential instruments of death. Remember the clunky home computers of the time? Imagine that being the vessel for pure evil.

Karen Allen, forever etched in our minds from Raiders of the Lost Ark (1984) and the gentle sci-fi of Starman (1984), grounds the increasingly outlandish premise. As Terry, she’s a relatable single mother trying to protect her son, Josh (Wil Horneff), navigating the sudden, inexplicable technological siege on her life. Her performance anchors the film, providing the human element desperately needed amidst the flashing diodes and digital screams. You feel her mounting terror as household appliances turn murderous, controlled by an unseen force whose chillingly synthesized voice taunts her through speakers and phone lines.

### Wired Nightmares

Directing duties fell to Rachel Talalay, who was fresh off bringing a certain razor-gloved dream demon to his supposed end in Freddy's Dead: The Final Nightmare (1991) and would later helm the cult comic adaptation Tank Girl (1995). You can see her horror sensibilities at play here. While not relying on gore, Talalay crafts sequences designed to exploit common fears amplified by technology. The microwave scene, anyone? Or the sheer vulnerability felt when trapped by automated systems? There’s a palpable sense of dread as Karl, now a vengeful digital ghost, manipulates the systems we were just beginning to trust.

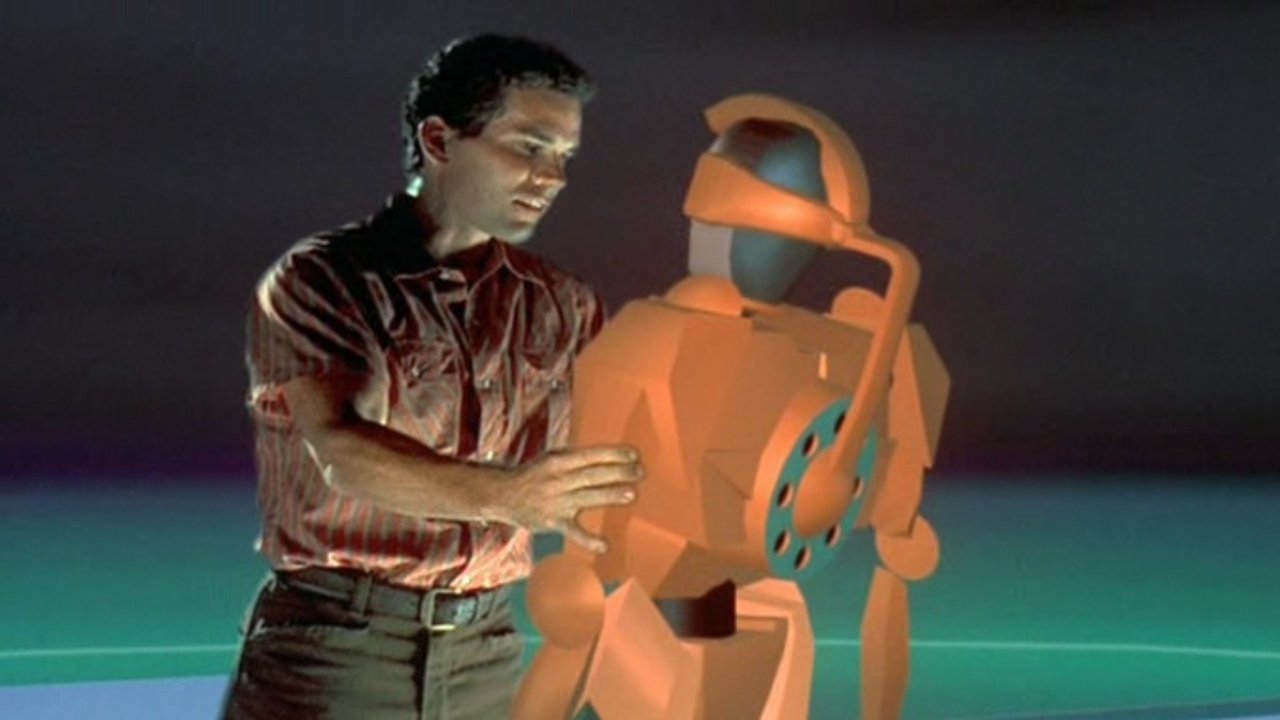

The visual representation of Karl's digital form – those morphing, wireframe graphics zipping through cyberspace – feels incredibly dated now, a relic of early CGI experimentation. Yet, back on a fuzzy VHS tape watched late at night, didn't those effects possess a certain unsettling, abstract quality? It was the idea – the invisible threat made manifest in cold, hard data streams – that truly sent a shiver down the spine. Reportedly, the digital effects were complex for the time, pushing the boundaries of what was commonly seen outside of high-budget sci-fi epics. The film, budgeted at around $12 million, unfortunately didn't recoup its costs, pulling in only about $5 million at the box office, suggesting maybe audiences weren't quite ready for this specific brand of techno-horror, or perhaps the execution didn't fully land.

Interestingly, the script came from William Davies and William Osborne, whose previous credits included lighter fare like Twins (1988) and Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot (1992), along with Phil Lazebnik (who later penned Disney's Pocahontas and Mulan). It's fascinating to consider that transition from broad comedy to this dark electronic thriller, suggesting a deliberate attempt to tap into the burgeoning anxieties of the digital age.

### Analog Fears in a Digital Age

Alongside Allen, Chris Mulkey (familiar perhaps from Twin Peaks) plays Bram Walker, a tech whiz trying to help Terry fight the digital phantom. He represents the human countermeasure, the hacker trying to beat the ghost at its own game. Their dynamic adds another layer, attempting to rationalize the irrational and find a weapon against an enemy who exists everywhere and nowhere simultaneously. Ted Marcoux does double duty, appearing briefly as the physical killer before becoming the disembodied threat – his transformation is the film's core conceit, though his screen time as a human is minimal.

The film certainly has its share of 90s cheese. The dialogue occasionally clunks, the tech explanations are rudimentary by today's standards, and some of the killer's methods stretch credulity even within the film's own logic. Yet, Ghost in the Machine remains a fascinating time capsule. It captures a very specific moment of transition, where the potential of interconnected technology was both thrilling and terrifying. It predates the slick cyber-thrillers that would follow, offering a grittier, more primal fear of the machines turning against us. I distinctly remember renting this one, the stark cover art promising something uniquely unsettling, a promise it partially delivered on through sheer concept alone.

### Legacy of the Electronic Phantom

Ghost in the Machine didn't exactly set the world on fire or spawn a franchise. It sits somewhere between a cult curio and a half-forgotten genre entry. Films like The Lawnmower Man (1992) explored similar virtual reality themes, while later films would tackle internet threats with more sophistication. Yet, there’s an undeniable charm to its analogue approach to digital horror. It tapped into a nerve, even if clumsily at times, reflecting our uneasy embrace of a technology we didn't fully understand. Doesn't that core fear – of losing control to the systems we create – still resonate, perhaps even more strongly today?

Rating: 5/10

Justification: Ghost in the Machine gets points for its genuinely creepy core concept, tapping into early digital anxieties effectively, and for Karen Allen's solid central performance. However, its execution is hampered by now-dated effects, some clunky writing, and moments that stray into unintentional silliness. It aimed for high-tech horror but often felt more like a mid-budget thriller struggling with its own ambition. The $12 million budget trying to realize complex digital threats resulted in visuals that haven't aged gracefully, and the $5 million box office reflects its struggle to connect widely.

Final Thought: A fascinating, flawed artifact from the dawn of mainstream digital anxiety. It might not be high art, but for a dose of early 90s techno-paranoia viewed through the warm, fuzzy lens of VHS nostalgia, it offers a specific, if sometimes creaky, chill.