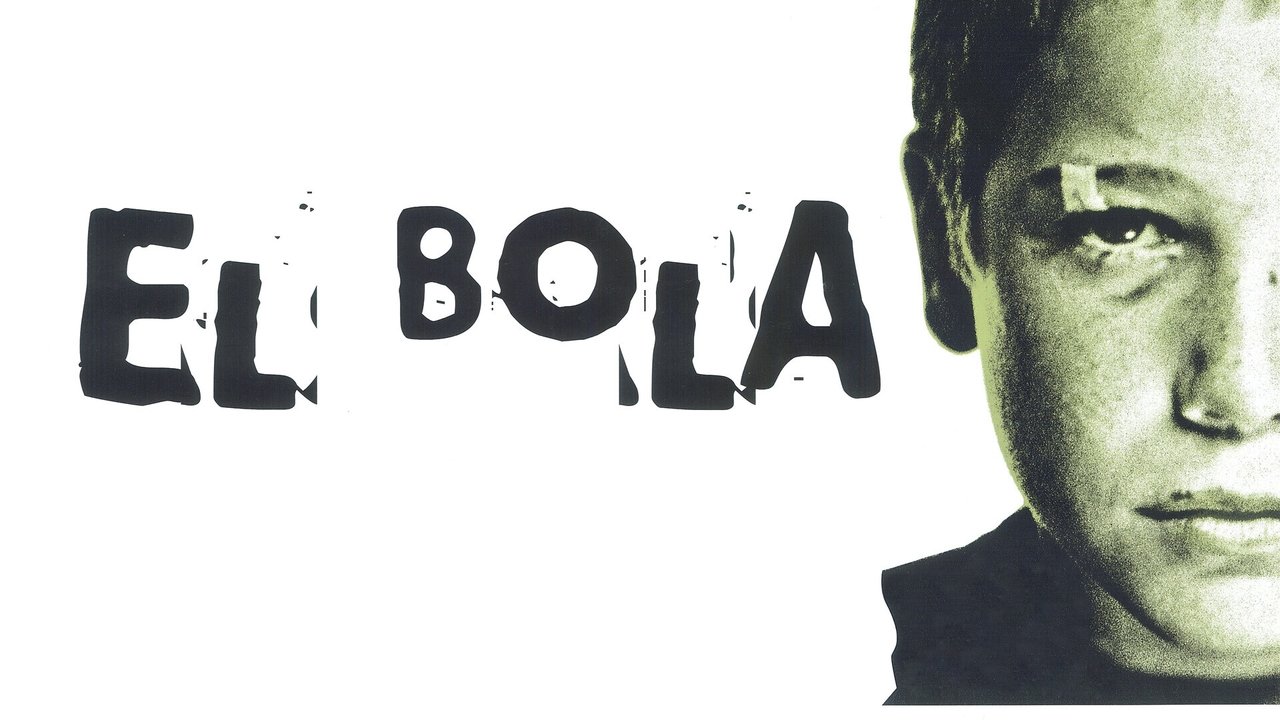

It arrives sometimes not with a bang, but with a click, a metallic skitter across pavement. That sound, the near-constant companion of twelve-year-old Pablo, known as "El Bola," is one of the first things that lodges itself in your memory after watching Achero Mañas's devastatingly powerful 2000 debut, Pellet (original title: El Bola). Released right at the cusp of a new millennium, perhaps just as the reign of the VHS tape was beginning its slow fade, this film felt less like a product of its specific year and more like a timeless, wrenching examination of hidden pain, the kind that festers behind closed doors in any era. Watching it again now, its impact hasn't softened; if anything, the clarity and courage of its storytelling feel even more vital.

### Two Households, Both Alike in Dignity (But Little Else)

The film draws its quiet power from a stark contrast. We have Pablo's world – claustrophobic, ruled by fear and the menacing presence of his father, Mariano (Manuel Morón), a man whose traditional values mask a terrifying brutality. Their small apartment feels suffocating, steeped in unspoken tension. Then, a new boy, Alfredo (Pablo Galán), arrives at school. Alfredo’s family represents an entirely different universe. His parents, José (Alberto Jiménez) and Marisa (Nieve de Medina), run a tattoo parlor. Their home is open, filled with conversation, understanding, and a modern acceptance that is alien to Pablo. It's through Alfredo's tentative friendship that Pablo glimpses a possibility of life beyond the silent suffering he endures.

Achero Mañas, directing his own Goya-winning screenplay, masterfully uses these contrasting environments. He doesn't just show us; he makes us feel the difference. The cramped, dimly lit spaces of Pablo's home versus the brighter, more bohemian feel of Alfredo's apartment become visual metaphors for the emotional landscapes the boys inhabit. It was Mañas's feature directorial debut, and the confidence on display is remarkable, earning him the Goya Award for Best New Director. Reportedly drawing from personal observations, Mañas crafts a narrative that feels achingly authentic, filmed in the working-class barrios of Madrid, which lend the film an undeniable sense of place.

### The Weight of a Small Steel Ball

At the heart of it all is Juan José Ballesta as Pablo. Just twelve years old during filming, Ballesta delivers a performance of staggering maturity and vulnerability. His "Bola," the ball bearing he constantly rolls and clicks, isn't just a toy; it's an anchor, a shield, a tiny piece of control in a life utterly dominated by fear. Watch his eyes: they dart, assess, plead, and sometimes, heartbreakingly, shut down completely. The way he flinches almost imperceptibly, the tension in his small shoulders – it’s a portrait of trauma etched with harrowing precision. It’s no surprise Ballesta won the Goya for Best New Actor; it’s one of those debut performances that feels less like acting and more like channeling something profoundly real. What does that constant clicking signify? Is it a desperate attempt to drown out the world, or perhaps a small, defiant rhythm against the silence imposed upon him?

### Friendship as Sanctuary

The tentative, growing bond between Pablo and Alfredo forms the film's emotional core. Alfredo isn't a saintly savior; he's a curious, fundamentally decent kid who slowly intuits that something is deeply wrong in his new friend's life. Pablo Galán plays him with a natural ease that provides the perfect counterpoint to Ballesta's tightly wound energy. Their interactions – sharing secrets, exploring the city, the simple act of being seen by someone outside his toxic family unit – offer Pablo moments of fragile hope. The scenes with Alfredo’s father, José, are particularly poignant. Alberto Jiménez, known perhaps to some for later roles but truly memorable here, portrays José as a compassionate, observant man who embodies a gentle, non-judgmental masculinity starkly different from Pablo's own father. His willingness to listen, to offer safety without demanding confession, is quietly heroic.

### Unflinching Honesty, Enduring Impact

Pellet does not shy away from the grim reality of child abuse. It handles its subject matter with sensitivity but also with an unflinching honesty that can be difficult to watch. There are no easy resolutions offered, no melodramatic flourishes. The violence, when it occurs or is implied, is brutal and deeply unsettling precisely because it feels grounded and horribly plausible. This isn't exploitation; it's a demand that we bear witness. The film sparked considerable conversation in Spain upon its release, forcing a difficult topic into the light – a testament to its power. It went on to win Best Film at the Goyas, cementing its place as a major work of contemporary Spanish cinema, all achieved on a relatively modest budget (around €1.5 million) that yielded significant audience connection.

Does the film offer hope? Perhaps not in a conventional sense, but in the resilience of its young protagonist, in the profound impact of kindness and friendship, and in the courage it takes to finally speak the unspeakable, there's a powerful affirmation of the human spirit's endurance. It reminds us that sometimes, the bravest act is simply reaching out, or allowing oneself to be reached.

***

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's exceptional execution across the board. Achero Mañas's direction and script are insightful and assured, handling incredibly sensitive material with grace and power. The performances, particularly Juan José Ballesta's unforgettable portrayal of Pablo, are raw and deeply affecting. Its realistic atmosphere and unflinching look at a difficult subject make it resonate long after viewing. While its 2000 release places it just outside the typical 80s/90s VHS heyday, its themes and gritty realism connect it spiritually to the powerful dramas of that preceding era, and it undoubtedly found its way into many VCRs, leaving an indelible mark.

Pellet is more than just a film; it's an experience that stays with you, a quiet clicking in the back of your mind reminding you of the hidden battles fought by the vulnerable, and the life-altering potential of simple human connection.