There's a certain quiet ache that settles in after watching Kids Return, a feeling familiar to anyone who's ever looked back at the crossroads of youth and wondered about the paths not taken. It lacks the explosive violence often associated with Takeshi Kitano's gangster flicks like Sonatine (1993), yet it carries its own profound weight. This 1996 film feels less like a narrative aggressively pushed forward and more like a collection of fragile moments, captured with a stillness that allows the unspoken emotions to resonate long after the screen fades to black. It’s the kind of film that rewards patience, inviting reflection rather than demanding reaction.

School Daze and Diverging Destinies

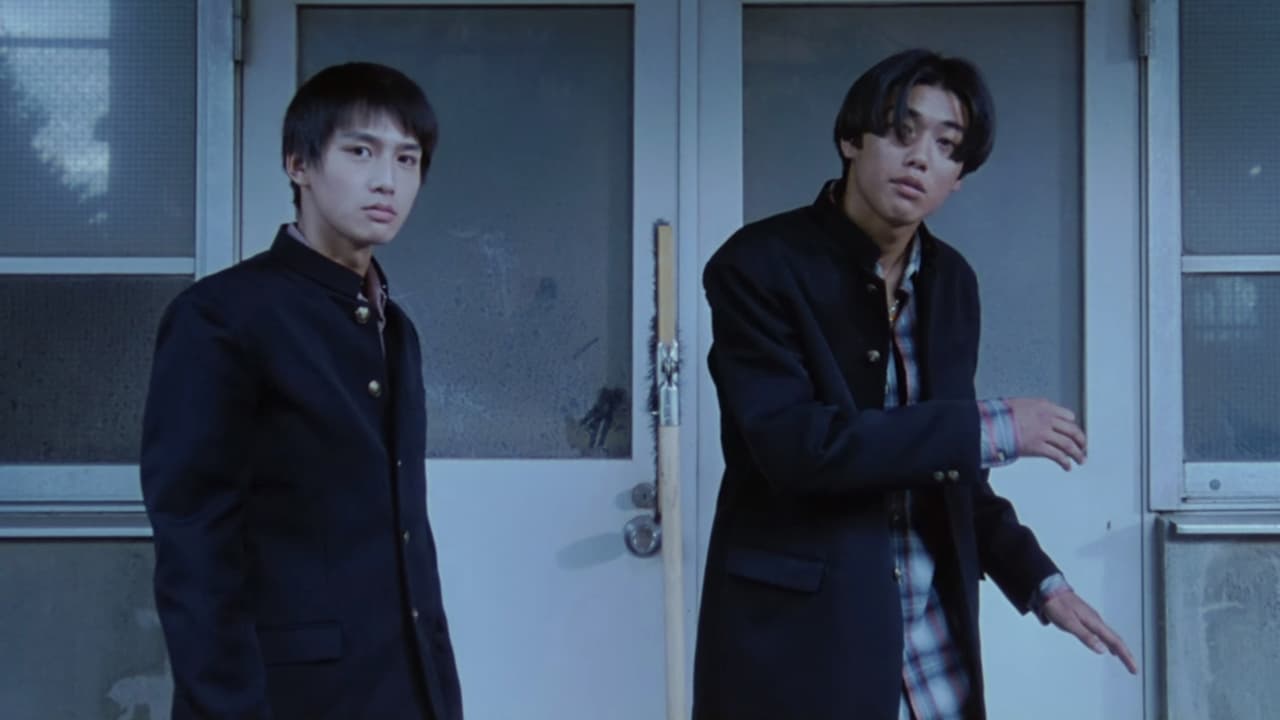

We meet Shinji (Masanobu Andō) and Masaru (Ken Kaneko) as high school dropouts, navigating that listless space between adolescence and adulthood with a mixture of bravado and cluelessness. They’re inseparable, pulling pranks, shirking responsibility, their energy directionless. There's an authenticity to their boredom, a palpable sense of youthful potential waiting for a spark. Kitano, who both wrote and directed, captures this aimlessness perfectly – the long takes, the quiet observations, the sudden bursts of awkward comedy that feel utterly true to teenage life. Remember that feeling of having the whole world ahead of you, yet being utterly stuck in the present? Kids Return bottles that sensation.

The catalyst for change comes almost accidentally. After Masaru gets roughed up, he drags Shinji to a boxing gym, intending to learn how to fight back. But it’s Shinji, the quieter, more introverted of the two, who discovers a genuine talent and passion for the sport. Masaru, perhaps feeling overshadowed or simply lacking the discipline, drifts towards the allure of the local yakuza boss. Their paths diverge, not through dramatic conflict, but through the subtle, almost inevitable pull of different inclinations and opportunities.

A Director Reborn

It’s impossible to discuss Kids Return without acknowledging the profound context of its creation. This was Takeshi Kitano’s first film after the devastating motorcycle accident in August 1994 that nearly killed him, leaving one side of his face paralyzed. The title itself, Kids Return, is often interpreted as signifying Kitano’s own return to filmmaking, perhaps even to life. Knowing this lends the film an extra layer of poignancy. Did his brush with mortality infuse the story with its reflective, almost elegiac tone? One senses a newfound appreciation for fragility, for the moments that define us, and for the idea of second chances, even if they remain elusive for the characters. The production itself was, understandably, delayed significantly as Kitano recovered. When he finally stepped back behind the camera, there was immense anticipation, and the resulting film felt quieter, more personal, less reliant on the shock tactics of his earlier work.

Authenticity in Performance and Place

Masanobu Andō and Ken Kaneko, relative newcomers at the time, are remarkable. Andō embodies Shinji’s quiet determination, his internal struggles conveyed through subtle shifts in expression rather than overt displays of emotion. We see the focus flicker in his eyes as he trains, the flicker of hope that maybe, just maybe, boxing offers a way out. Kaneko perfectly captures Masaru’s swagger, his gradual slide into a world he doesn’t fully understand, mistaking cheap power for genuine respect. Their bond feels real, a friendship built on shared history and unspoken understanding, which makes their drifting apart all the more affecting.

Kitano’s direction is characteristically minimalist. He trusts his actors and the inherent drama of the situation. The boxing sequences are gritty and realistic, focusing on the effort and the physical toll rather than flashy choreography. Similarly, the portrayal of the low-level yakuza world avoids glorification; it’s depicted as mundane, almost pathetic, stripping away any romanticism. The score by longtime collaborator Joe Hisaishi (famous for his work with Studio Ghibli) is crucial, its melancholic melodies perfectly complementing the film's mood without ever becoming intrusive. It underscores the sense of yearning and lost time that permeates the narrative.

That Lingering Final Question

Spoiler Warning! The film culminates in a scene where Shinji and Masaru reconnect, both having seemingly failed in their chosen paths. They ride a bicycle together, much like they did in their school days. Masaru turns to Shinji and asks, "Is it over for us?" Shinji replies, "Don't be silly. We haven't even started yet." It's a line that hangs heavy in the air. Is it a statement of naive optimism, a refusal to accept defeat? Or is it a tragically ironic acknowledgment that their best days, their days of pure potential, are already behind them? Kitano leaves it deliberately ambiguous, forcing us to confront our own interpretations of hope, failure, and the passage of time. What does that final exchange truly signify about resilience versus resignation?

Kids Return isn't a feel-good movie, nor is it a straightforward rise-and-fall narrative. It's a slice of life, imbued with a bittersweet understanding of how easily youthful promise can curdle into regret. It captures that specific ache of looking back, the blend of nostalgia and melancholy for what might have been. It’s a film that resonated deeply upon its release in Japan, winning several Awards of the Japanese Academy, including Best Newcomer for Masanobu Andō, signaling that Kitano had returned not just physically, but artistically revitalized.

Rating: 8.5/10

This score reflects the film's quiet power, its authentic performances, Kitano's masterful direction, and its poignant exploration of themes that feel universal. It lacks the immediate visceral impact of some of his other works, relying instead on a cumulative emotional effect that lingers. It’s a deeply personal film, born from adversity, that speaks volumes about hope, failure, and the enduring echoes of youth.

Watching it now, decades later, perhaps on a format far removed from the original VHS tapes it likely circulated on among cinephiles, that final line still hits hard. Haven't we all felt, at some point, like we haven't even started yet, even when the evidence suggests otherwise?