Okay, fellow travelers on the rewind journey, let's set the VCR tracking for a trip slightly beyond our usual 90s stomping grounds, right to the cusp of the new millennium. While the year 2000 technically nudges it past the decade line, Brian De Palma’s Mission to Mars feels intrinsically linked to the big-budget, earnest sci-fi spectacles that graced our screens (and video store shelves) throughout the late 90s. It arrived just as DVD was starting its ascent, but for many of us, this grand, sometimes baffling space opera likely spun its tale on a trusty VHS tape, its widescreen ambitions perhaps slightly compromised by our 4:3 CRT screens.

### A Grand Voyage with a Familiar Crew

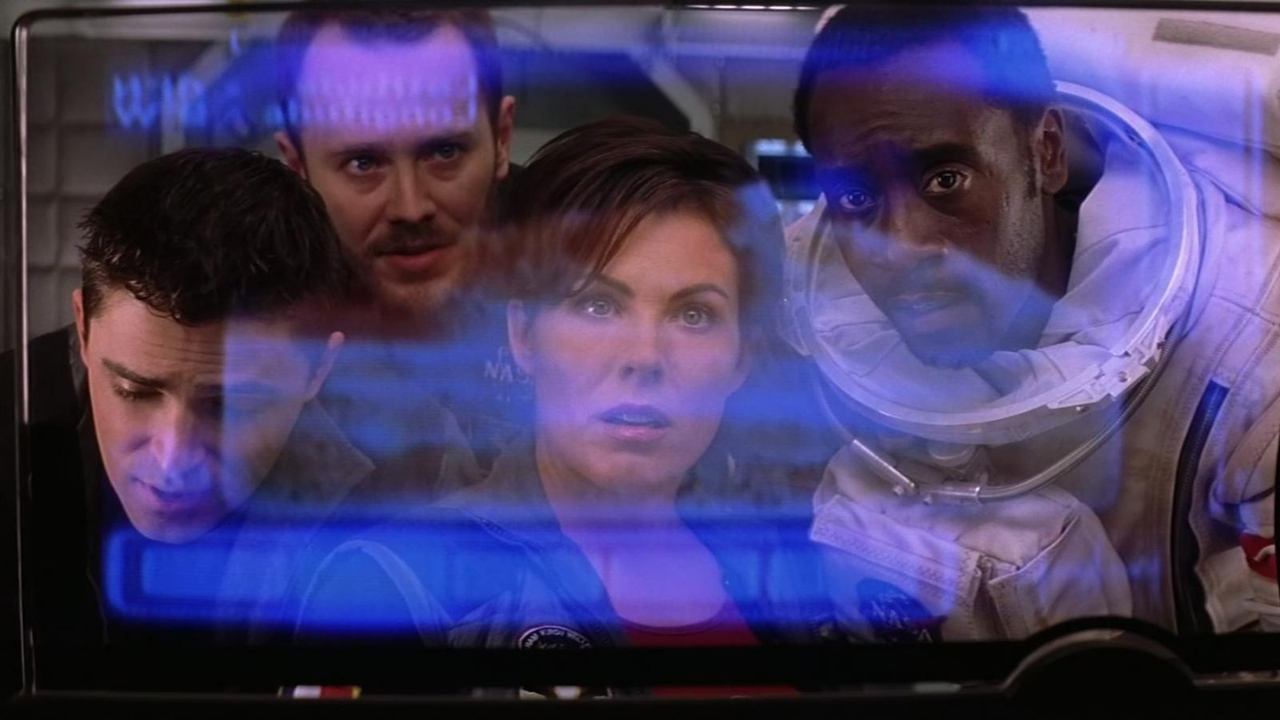

The premise launches with familiar, almost comforting sci-fi beats: humanity’s first manned mission lands on Mars in 2020 (a future that felt comfortably distant back then!), only for disaster to strike in the form of a mysterious, catastrophic event. Enter the rescue crew, led by the stoic Jim McConnell (Gary Sinise, bringing his reliable everyman gravity, not long after Apollo 13 established his space-faring credentials) and Woody Blake (Tim Robbins, reuniting with Sinise after their iconic pairing in The Shawshank Redemption). They’re joined by Terri Fisher (Connie Nielsen) and Phil Ohlmyer (Jerry O'Connell), with Luke Graham (Don Cheadle) as the lone survivor on the Red Planet they’re racing to save. It’s a stellar cast, filled with faces we knew and trusted, lending immediate weight to the perilous journey.

Directed by Brian De Palma, a filmmaker renowned for his stylish thrillers like Carrie (1976), Scarface (1983), and the first Mission: Impossible (1996), this felt like a significant departure. Could the master of suspense and split-diopter shots tackle the vastness and wonder of space? The answer, much like the film itself, is complex and fascinatingly uneven.

### Ambitious Visions, Earthbound Oddities

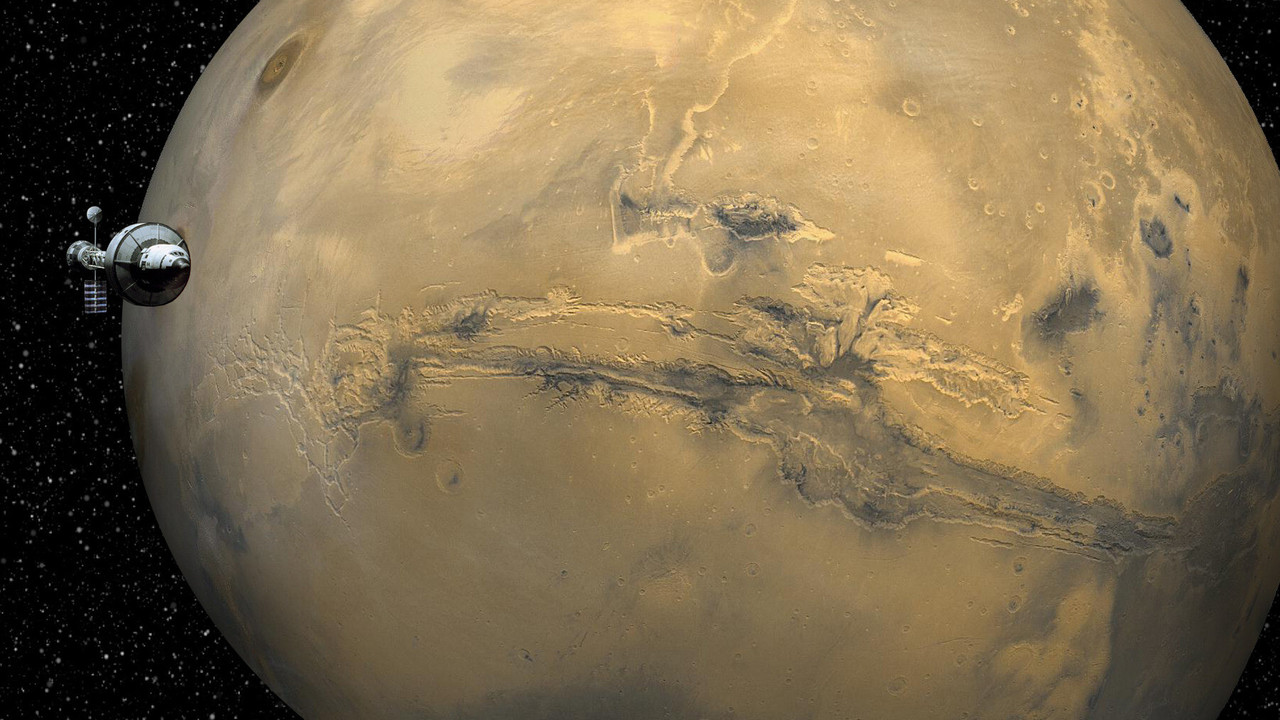

Mission to Mars aims high, striving for a sense of awe and realism reminiscent of Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Early scenes meticulously depict the mechanics of space travel – the rotating gravity sections of the rescue ship, the procedural checks, the inherent dangers of EVA walks. There's a tangible weight to the technology, underscored beautifully by a sweeping, majestic score from the legendary Ennio Morricone. One particularly memorable, almost balletic sequence involves Woody and Terri sharing a zero-gravity dance to Van Halen – a moment of human connection amidst the cold void that feels both charmingly dated and genuinely sweet.

But where the film sometimes stumbles is in its tonal shifts. It oscillates between hard sci-fi survival (a harrowing micrometeoroid shower sequence stands out) and moments that dip into almost sentimental melodrama. Interestingly, the film’s origins trace back to a Disney theme park attraction of the same name (operational at Disneyland from 1975 to 1993), though the film takes a decidedly more serious, less overtly "theme park" approach than, say, the later Pirates of the Caribbean franchise. The script, penned by Jim Thomas & John Thomas (who gave us the muscular action of Predator) and Graham Yost (the high-octane mind behind Speed), feels like it’s pulling in multiple directions – part survival thriller, part philosophical space exploration, part creature feature (that Martian vortex!).

### Retro Fun Facts: Behind the Red Dust

The production itself was a significant undertaking, with a budget reportedly hovering around $100 million – a hefty sum for the time. Unfortunately, it didn't quite ignite the box office, pulling in about $111 million worldwide. Adding to its woes, it faced direct competition from another Mars-centric film released later the same year, Red Planet, which also struggled commercially. It seemed audiences in 2000 weren't quite ready for a double dose of Martian misfortune.

While De Palma is known for his visual trademarks, Mission to Mars feels somewhat restrained compared to his usual flair. There are glimpses – some meticulous long takes, a focus on surveillance and screens – but it often adopts a more conventional blockbuster style. The visual effects, a blend of practical models and burgeoning CGI, have that distinct early 2000s look – impressive in scale, occasionally showing their digital seams today, but possessing a certain handcrafted charm we often miss now. The depiction of the Martian face structure and the final encounter inside remain visually striking, if philosophically divisive. Initial critical reactions were notably harsh (it currently sits at a chilly 24% on Rotten Tomatoes), often criticizing the pacing and the third act's sharp turn into speculative territory.

### A Flawed Artifact Worth Revisiting?

Watching Mission to Mars today is an intriguing experience. It’s undeniably earnest, reaching for a sense of wonder and cosmic significance that’s quite disarming. Yes, the dialogue can sometimes be clunky, and the pacing occasionally drags during the long transit sequences. The final act reveal (Spoiler Alert! regarding the nature of the Martian structure and humanity's origins) was, and remains, a point of contention – some find it profoundly imaginative, others frustratingly simplistic or even silly.

Yet, there's an undeniable pull to its ambition. It feels like a film from that specific turn-of-the-millennium moment – hopeful about space travel, grappling with big questions, and showcasing the evolving tools of digital filmmaking. It lacks the grit of Alien or the intellectual rigor of 2001, but it possesses a unique personality – a sort of grand, slightly naive space opera that genuinely tries to inspire awe. Perhaps its sincerity, sometimes bordering on sappiness, is precisely what makes it memorable, flaws and all. Did you desperately want one of those cool rotating ship interfaces back then? I know a part of me did.

VHS Heaven Rating: 6/10

Justification: Mission to Mars earns a 6 for its sheer ambition, strong ensemble cast (Sinise, Robbins, Cheadle shine), impressive production design, and moments of genuine visual spectacle, particularly for its era. Ennio Morricone's score elevates the proceedings significantly. However, it loses points for its uneven tone, sometimes sluggish pacing, clunky dialogue, and a divisive third act that doesn't entirely mesh with the preceding survival elements. It’s a film whose reach sometimes exceeds its grasp, reflected in its mixed critical reception and modest box office return despite a hefty budget and a famed director at the helm.

Final Thought: Like a hopeful message beamed across the cosmos, Mission to Mars might not have landed perfectly, but its earnest attempt to capture the wonder of the unknown makes it a fascinating, if flawed, artifact from the dawn of 21st-century sci-fi cinema – a grand voyage definitely worth remembering from the tail-end of the VHS era.