"Some doors are locked for a reason." That tagline, stark against the often lurid cover art staring back from the video store shelf, promised something genuinely disturbing. 8MM, released in the twilight of the 90s (1999, to be exact), wasn't your typical Hollywood thriller. It felt dangerous, coated in a layer of grime that clung to you long after the VCR whirred to a stop. This wasn't a film you watched casually; it was one you braced yourself for, peering into an abyss that felt uncomfortably real.

Into the Static Abyss

The premise itself is a gut punch: Tom Welles (Nicolas Cage), a surveillance expert living a quiet suburban life, is hired by a wealthy widow to investigate a reel of 8mm film found in her late husband's safe. The film appears to depict the actual murder of a young woman – a snuff film. Welles's task isn't just to determine its authenticity but to find the girl, hopefully alive. What follows is a descent, not into a fantastical underworld, but into the grimy, pathetic, and terrifyingly banal reality of illicit pornography and extreme violence lurking beneath society's surface. Directed by Joel Schumacher – a filmmaker whose career swung wildly from the neon gothic of The Lost Boys (1987) to the... well, other kind of gothic in Batman & Robin (1997) – 8MM feels like an attempt to grapple with genuine darkness, miles away from caped crusaders.

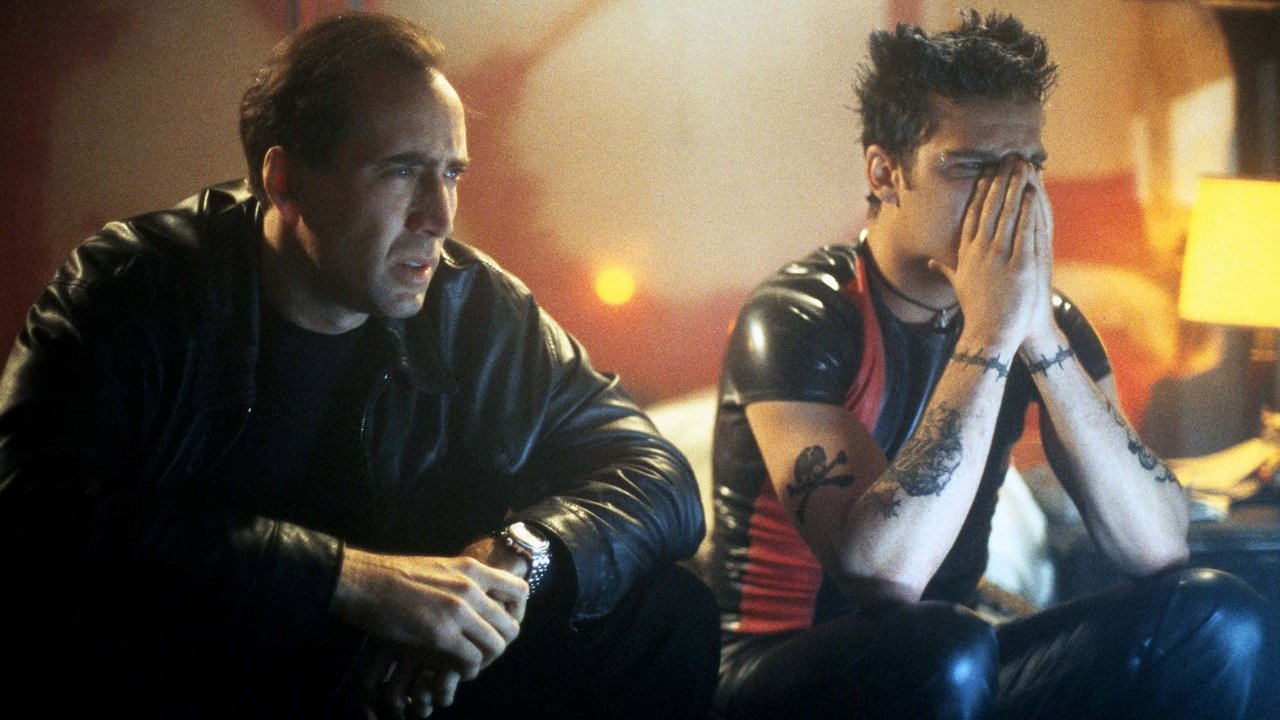

Cage Descending

Nicolas Cage is our guide, and it’s one of his quintessential late-90s performances – coiled, increasingly frayed, his eyes reflecting the horrors he witnesses. Welles starts as a competent professional, but the deeper he goes, the more the darkness infects him. It’s a performance that relies less on explosive outbursts (though there are moments) and more on a simmering, internalized disturbance. Remember watching him then? There was always this feeling Cage could truly go there, and 8MM demanded it. He’s aided by a perfectly cast Joaquin Phoenix as Max California, a punk-rock adult video store clerk who becomes Welles's cynical guide through the L.A. underground. Phoenix brings a necessary, albeit bleak, counterpoint to Cage's intensity. And then there's James Gandolfini, pre-Tony Soprano but already mastering menacing sleaze, as the repellent Eddie Poole. His performance is skin-crawlingly effective, a portrait of casual depravity.

The Shadow of Se7en

You can't talk about 8MM without mentioning Andrew Kevin Walker. Fresh off the monumental success of his screenplay for Se7en (1995), Walker penned this descent into human ugliness. However, tales from the production suggest a familiar Hollywood story: Walker's original script was reportedly even bleaker, more nihilistic, focusing perhaps more psychologically on Welles's corruption. Schumacher and the studio allegedly pushed for a more conventional thriller structure, including a more defined "action" climax. This tension is palpable in the final film – it wants to be a profound exploration of the abyss, but sometimes defaults to thriller mechanics. Walker himself was reportedly unhappy with the final product, which adds another layer to the film’s troubled, dark aura. It cost around $40 million to make, ultimately grossing just under $100 million worldwide – respectable, but perhaps not the Se7en-level hit some anticipated, likely hampered by its incredibly grim subject matter.

Atmosphere Over Answers

Where 8MM truly succeeds, especially viewed through that nostalgic VHS lens, is its atmosphere. Schumacher, working with cinematographer Robert Elswit (who would later win an Oscar for There Will Be Blood), crafts a world saturated in decay. The rain-slicked streets, the flickering neon of adult shops, the sterile opulence hiding rot, the genuinely unsettling locations – it all contributes to a pervasive sense of unease. The film doesn't flinch, presenting its underworld without glamour. Does that unnerving sequence involving the character known only as 'Machine' still feel deeply uncomfortable? The practical effects, while not monster-movie makeup, were focused on creating a believable, repellent reality, contributing significantly to the film's power to disturb back then. The score by Mychael Danna is equally crucial, a low, throbbing presence that enhances the dread rather than resorting to jump-scare stingers.

A Tarnished Tape?

Revisiting 8MM now evokes that specific late-90s feeling – a grappling with the darker aspects of the internet's rise and the accessibility of extreme content. It was controversial then, accused by some critics of being exploitative itself. Does it entirely avoid that charge? Perhaps not entirely. The line between depicting darkness and reveling in it is thin, and 8MM walks it precariously. It lacks the tight, theological horror of Se7en, occasionally feeling more like a grim procedural. Yet, its power to unsettle remains potent. I distinctly remember the feeling after renting this one – it wasn’t excitement, but a heavy, lingering disquiet. It was the kind of film whispered about, dared to be watched.

VHS Heaven Rating: 7/10

8MM is a challenging, often unpleasant film that earns its 7/10 rating through its commitment to a suffocatingly dark atmosphere, strong central performances (especially Cage plumbing the depths), and its unflinching (if sometimes clumsy) stare into human depravity. It’s hampered slightly by script compromises and a third act that leans into convention, preventing it from reaching the classic status of its spiritual predecessor, Se7en. However, it remains a potent and memorable slice of late-90s grimness, a film that truly felt like forbidden knowledge glimpsed on a flickering CRT screen late at night.