The reflection staring back isn't always your own. Sometimes, it's fractured, distorted, menacing. Sometimes, it carries the weight of expectations you’re desperately trying to shed. That's the chilling space Satoshi Kon’s 1998 directorial debut, Perfect Blue, inhabits – a space where the bright lights of pop stardom cast the darkest, most suffocating shadows. This isn't your typical late-90s anime; forget giant robots or magical girls. This is a razor-sharp psychological descent that burrows under your skin and stays there, a disquieting masterpiece that feels ripped from the anxieties of the burgeoning internet age, even when viewed through the soft static of a well-worn VHS tape.

### From Pop Princess to Paranoid Prey

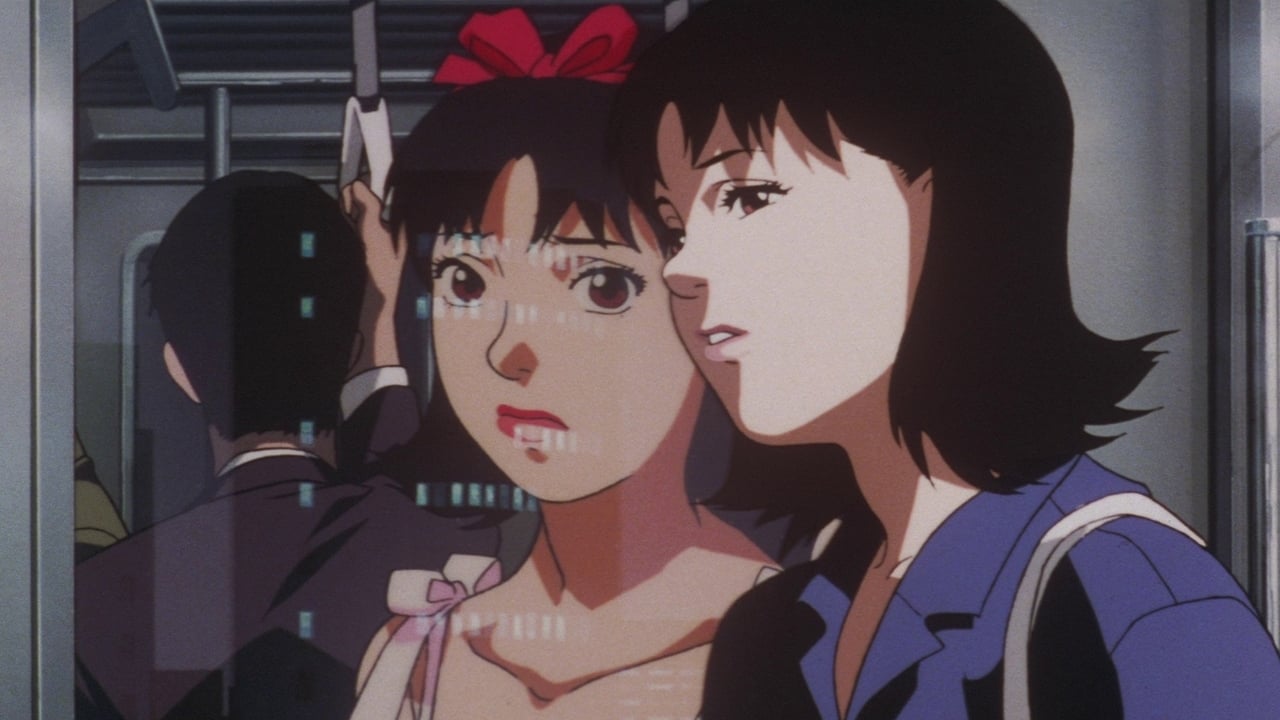

The premise seems straightforward enough: Mima Kirigoe (Junko Iwao delivering a hauntingly vulnerable performance), lead singer of the bubbly J-Pop trio CHAM!, decides to leave music behind to pursue a serious acting career. It’s a move met with dismay by her more obsessive fans, particularly an unnerving figure known only as Me-Mania. Simultaneously, Mima discovers "Mima's Room," a fan website detailing her innermost thoughts and daily activities with disturbing accuracy. As she takes on increasingly risqué and psychologically demanding acting roles, designed to shatter her 'good girl' idol image, the lines between her life, her roles, and the idealized Mima perpetuated online begin to violently blur. Is she losing her mind, or is something far more sinister stalking her every move?

### The Kon Effect: Editing as Weapon

What elevates Perfect Blue beyond a standard thriller plot is Satoshi Kon's virtuosic direction, particularly his revolutionary use of editing. Kon, who sadly left us far too soon, possessed an almost supernatural ability to dissolve reality through seamless, often jarring, match cuts and transitions. Scenes bleed into one another; Mima rehearsing a traumatic scene for her TV drama Double Bind merges indistinguishably with perceived threats in her real life. Dreams, hallucinations, online personas, and waking moments collapse into a bewildering, terrifying mosaic. You, the viewer, become as disoriented as Mima, questioning every perception. Doesn't that feeling of losing your grip, masterfully orchestrated through cuts, still feel incredibly potent? It’s a technique Kon would refine in later works like Paprika (2006), but its raw, brutal effectiveness here is breathtaking.

### Retro Fun Facts: A Troubled Birth

The journey of Perfect Blue to the screen is almost as fascinating as the film itself. Originally conceived as a live-action adaptation of Yoshikazu Takeuchi's novel, budget constraints forced a shift to animation. Enter Satoshi Kon, initially hired as an animator, who saw the potential to transform the material. He significantly reworked the script with writer Sadayuki Murai, ditching much of the novel's plot to focus intensely on Mima's psychological disintegration and themes of identity, voyeurism, and obsessive fandom – themes that feel eerily prescient today. It's said that Kon embraced the freedom animation offered, allowing him to depict the seamless blending of reality and hallucination in ways live-action couldn't easily achieve at the time. The film's production wasn't lavish; its estimated budget was relatively modest for feature animation (around ¥300-400 million JPY, perhaps $2.5-3.5 million USD back then), forcing creative solutions. Yet, this constraint likely sharpened its focus, resulting in a lean, mean, psychologically devastating piece of cinema.

### The Unflinching Gaze

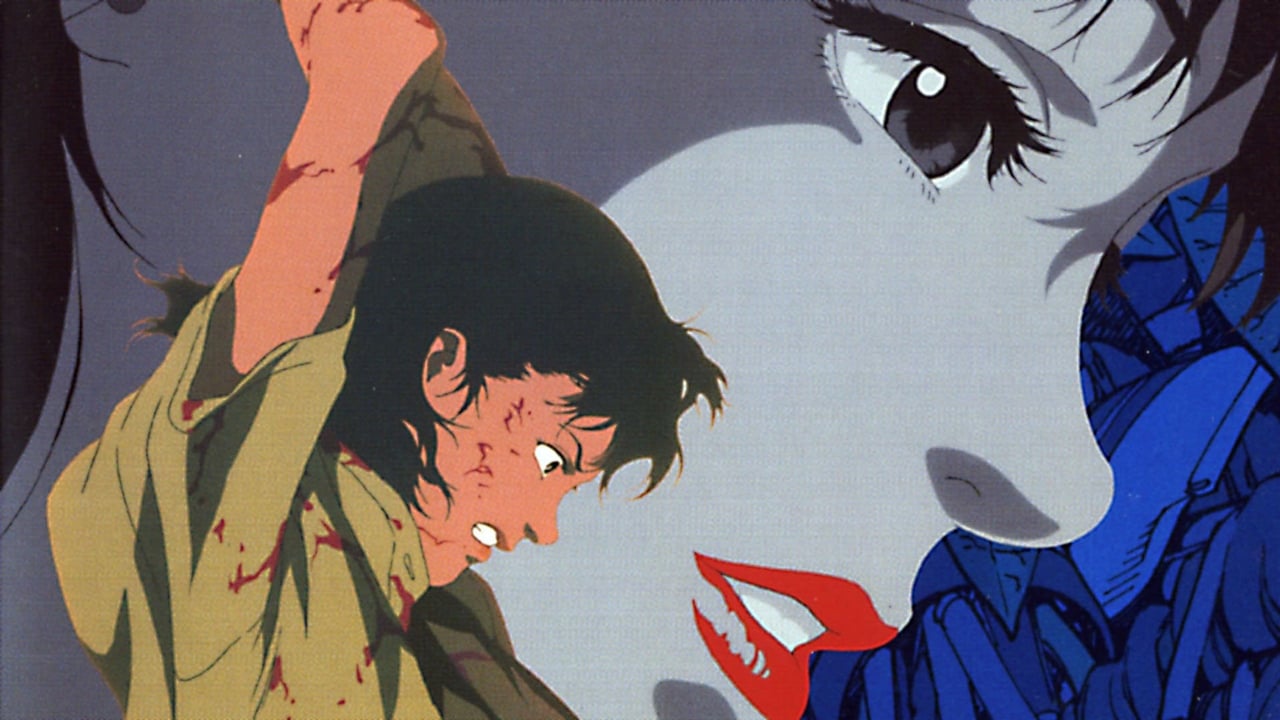

Perfect Blue does not shy away from disturbing content. It tackles themes of sexual exploitation in the entertainment industry, the psychological toll of fame, and the dark side of fan culture with unflinching honesty. The infamous rape scene Mima films for Double Bind is brutal not just in its depiction, but in how Kon frames its devastating impact on her psyche, blurring the line between performance and trauma. The animation itself, while perhaps appearing slightly dated compared to modern high-budget anime, possesses a raw, grounded quality that enhances the horror. The character designs feel real, vulnerable, making the violations against Mima – both physical and psychological – feel intensely personal and deeply unsettling. The film earned an R rating (or equivalent) in most territories, a testament to its mature and challenging nature, a far cry from the more mainstream anime hitting Western shores on VHS around the same time.

### Spoiler Alert! The True Face of Obsession

The climactic reveal of the true antagonist – not the lumbering Me-Mania, but Mima’s seemingly supportive manager Rumi Hidaka (Rica Matsumoto), driven mad by her own faded aspirations and embodying the 'ideal' Mima persona – is a gut punch. Rumi's dissociation, believing she is the real Mima while the actual Mima is an imposter, is the terrifying culmination of the film's exploration of fractured identity. Me-Mania was merely a pawn, manipulated by the deeper, more insidious obsession festering closer to home. Did that twist genuinely shock you back then? It reframes the entire film, turning the stalker narrative inward and exposing the terrifying potential for self-destruction projected onto another.

### Legacy of a Disturbing Vision

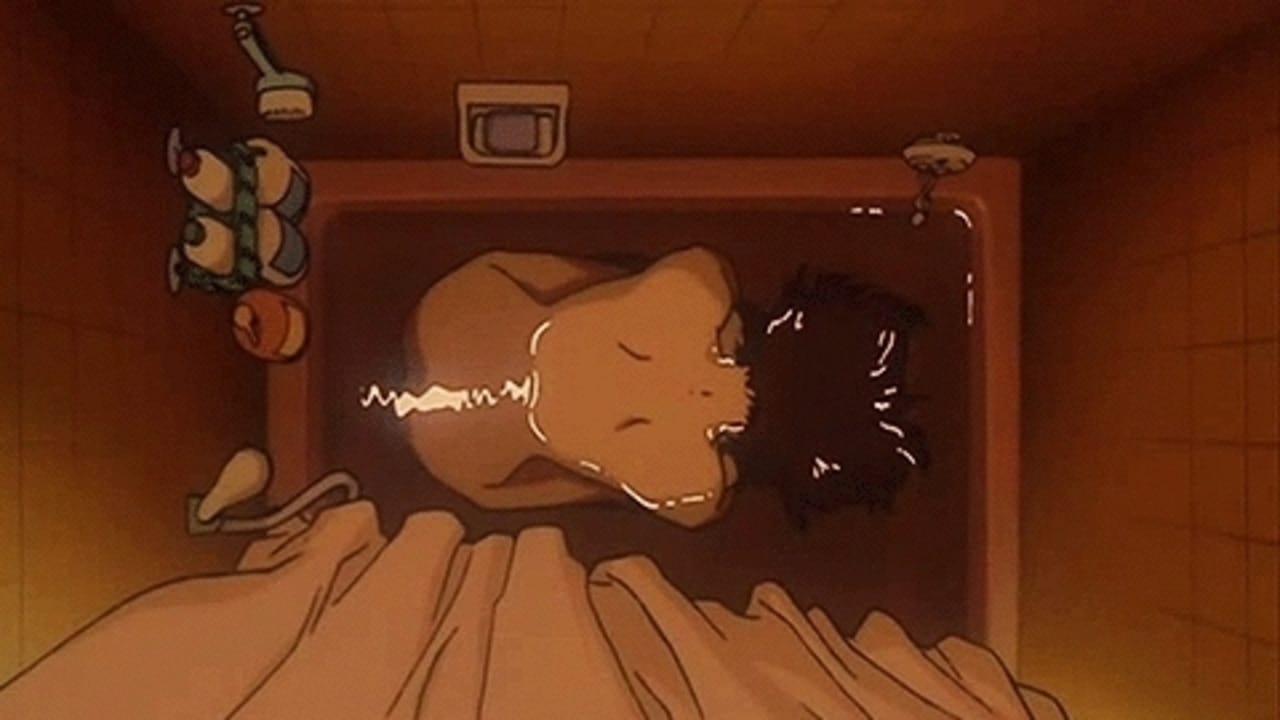

Perfect Blue remains a landmark achievement. It demonstrated the power of animation to tackle complex, adult psychological horror with nuance and visceral impact. Its influence is undeniable; filmmaker Darren Aronofsky bought the remake rights solely to recreate a specific sequence (the bathtub scene) for Requiem for a Dream (2000) and later explored similar themes of performance, obsession, and fractured identity in Black Swan (2010), which many see as a spiritual successor. For many viewers renting it from the "Anime" or perhaps even "Horror" section of the video store back in the late 90s or early 2000s, expecting something entirely different, Perfect Blue was likely a shocking, unforgettable experience. It challenged perceptions of what animation could be.

Rating: 9/10

This near-perfect score reflects Perfect Blue's masterful direction, its chillingly relevant themes, and its unforgettable psychological impact. The animation might show its age slightly in fluidity compared to modern standards, but its raw effectiveness and Kon's visionary editing remain undiminished. It’s a demanding, often unpleasant watch, but its exploration of identity, fame, and the dark corners of the human psyche is profoundly executed.

Perfect Blue isn't just a film; it's an experience that lingers, a haunting reminder of the fragile boundary between the self we project and the often terrifying reality lurking beneath the surface. It’s a vital piece of 90s cinema that proved animation could be as deeply disturbing and thought-provoking as any live-action thriller, leaving a chill that the rewind button couldn’t erase.