Okay, pull up a chair, maybe pour yourself something strong. We're not dusting off a feel-good blockbuster today. Instead, we're cracking open the controversial case of Adrian Lyne's 1997 adaptation of Lolita. It's a film that arrived not with the usual fanfare of a major release, but almost furtively, premiering on cable television in the US after a torturous journey finding distribution. That very struggle speaks volumes about the source material and the anxieties of the late 90s – a signpost of just how radioactive Vladimir Nabokov's masterpiece remained, even decades after its publication.

Walking the Narrative Tightrope

Adapting Lolita is less a filmmaking challenge and more like handling unstable dynamite. Nabokov’s novel is a linguistic marvel, a dizzying labyrinth built from the unreliable perspective of Humbert Humbert, a profoundly disturbed and self-justifying paedophile. Stanley Kubrick, in his 1962 version, sidestepped much of the explicit darkness through satire and implication, constrained by the censorship of his time. Adrian Lyne, known for his visually charged, often provocative explorations of sexuality like Fatal Attraction (1987) and 9½ Weeks (1986), aimed for something different – a more direct, perhaps more faithful rendering of Humbert’s obsessive narrative, penned here by Stephen Schiff. The question hanging heavy in the air, then and now, is: can such a story be told visually without tipping into exploitation, or worse, romanticization?

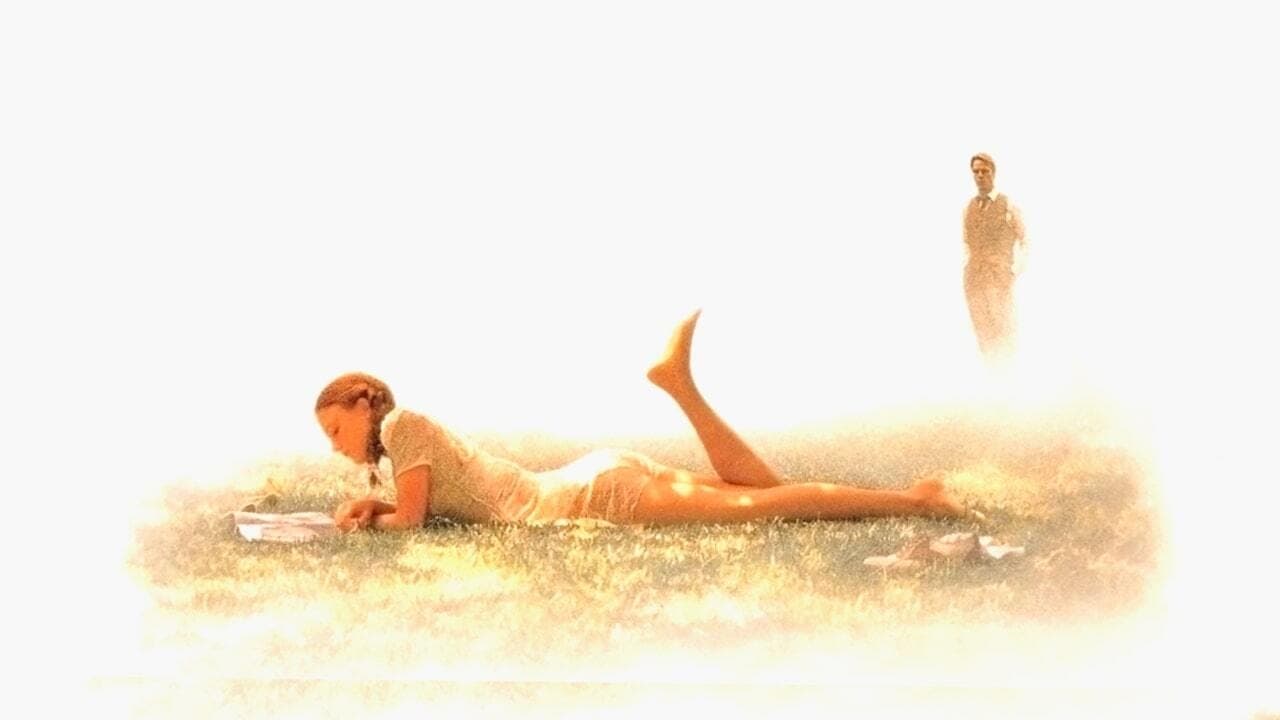

Lyne’s signature visual gloss is immediately apparent. The film is often beautiful to look at, capturing the hazy, sun-drenched Americana of Humbert and Lolita's cross-country journey. Yet, this very aesthetic becomes part of the film’s central tension. Does the polish soften the horror, or does it subtly underscore the seductive trap of Humbert's own warped perceptions? There's a discomfort in watching Lyne frame scenes with undeniable artistry while depicting monstrous acts. It forces a confrontation, making the viewer complicit in a way Kubrick’s more detached version perhaps didn't.

The Weight on Young Shoulders

Central to the film’s uneasy power are the performances. Jeremy Irons, an actor never afraid of complex, even unsympathetic roles (think Dead Ringers (1988)), embodies Humbert Humbert with a chilling weariness. He doesn't shy away from the character's predatory nature, but he also conveys the pathetic self-deception and intellectual vanity Nabokov wrote. Irons carries the weight of Humbert’s internal monologue, the flowery prose masking a rotten core, making the moments of supposed tenderness feel utterly corrupted. It’s a performance that aims for the novel’s ambiguity, capturing the man who could charm and appall in the same breath.

Then there's Dominique Swain, plucked from relative obscurity after a reported search involving thousands of young actresses. Taking on the role of Dolores Haze at just 15-16 years old was an immense undertaking. Swain navigates treacherous territory, portraying Lolita not merely as a victim, but as a complex young person – sometimes childish, sometimes defiant, possessing an awareness that flickers beneath the surface. Lyne often focuses on her reactions, her moments of boredom or fleeting independence, reminding us of the person being consumed by Humbert's obsession. It's a performance burdened by the very nature of the role, yet Swain finds moments of resilience that prevent Lolita from becoming purely symbolic. Supporting roles are strong too, with Melanie Griffith offering a brittle, tragicomic turn as the doomed Charlotte Haze, and Frank Langella bringing an unnerving, almost spectral presence to the enigmatic Clare Quilty.

Echoes of Controversy and Craft

The film's troubled path to viewers is a significant part of its story. Financed largely by European sources with a hefty budget (reported around $62 million), its inability to secure a mainstream US theatrical distributor highlighted the perceived toxicity of the subject matter. Showtime eventually aired it in 1997, followed by a limited theatrical run via Samuel Goldwyn Films nearly a year later. It barely scraped back $1 million at the US box office, a commercial footnote despite the pedigree involved. This reception felt less like a verdict on the film's quality and more like a reflection of societal unease. Was it possible, distributors seemed to ask, to market this faithfully dark adaptation without causing widespread offense?

Digging into its creation reveals Lyne's meticulous, almost obsessive approach. The script aimed to incorporate more of Nabokov's plot points and tone than the 1962 film, including the bleak ending. Shooting occurred primarily across Texas and Louisiana, convincingly doubling for the Northeastern settings and the cross-country landscapes described in the novel. Even Ennio Morricone's score contributes significantly, lending a mournful, almost operatic quality that contrasts sharply with the often sordid events unfolding on screen. It's a technically accomplished film, clearly crafted with intent, even if that intent remains deeply unsettling.

Does It Hold Up?

Revisiting Lyne's Lolita now, perhaps after finding a worn copy tucked away at a flea market or recalling its hushed arrival on late-night cable, is still a challenging experience. It lacks the satirical bite of Kubrick's film, opting instead for a more immersive, psychologically direct approach that forces proximity to Humbert's poisonous perspective. It's undeniably uncomfortable, as it should be. Does Lyne's visual style sometimes risk aestheticizing the abhorrent? Perhaps. But it also refuses easy answers or moral clarity, demanding the viewer grapple with the ugliness presented. It remains a potent, if deeply flawed, attempt to wrestle Nabokov's provocative text onto the screen.

Rating: 6/10

The rating reflects a film that succeeds in its difficult performances (Irons is compellingly repulsive, Swain handles an impossible role with maturity) and its atmospheric rendering of a specific American landscape corrupted by obsession. It’s technically polished and arguably more faithful to the novel's narrative arc than Kubrick's version. However, its visual richness sometimes sits uneasily with the subject matter, and the inherent difficulty of adapting Humbert's voice without implicitly validating it remains a significant hurdle. The film’s troubled release history also speaks volumes. It’s a serious, often disturbing work, but one that ultimately feels less definitive and more like a fascinating, deeply uncomfortable artifact of late-90s cinematic anxiety.

What lingers most isn't necessarily a specific scene, but the pervasive sense of unease, the feeling of being trapped within a beautifully rendered nightmare. It serves as a stark reminder that some stories, no matter how artfully told, forever carry the weight of their inherent darkness.