### Echoes in the Neon Rain: Contemplating Chinese Box (1997)

There's a particular kind of quiet that settles over a city just before dawn, a brief pause before the relentless pulse resumes. Watching Wayne Wang's Chinese Box feels something like inhabiting that fragile moment, extended over six months. It captures Hong Kong in the final breath before the 1997 handover to China, not through grand political pronouncements, but through the intimate anxieties and fleeting connections of people adrift in history's tide. It’s a film less concerned with plot mechanics than with atmosphere, mood, and the weight of impending change – a potent cocktail that felt both exotic and deeply human spilling from the VCR back in the day.

A City Holding Its Breath

What strikes you immediately, and lingers long after, is how tangible the film makes that specific moment in time. Wayne Wang, known then for the warmth of The Joy Luck Club (1993) and the cool intimacy of Smoke (1995), achieves something remarkable here by filming during the actual lead-up to the handover. This wasn't a recreation; it was immersion. News footage, street celebrations, palpable public uncertainty – it all bleeds into the narrative, blurring the line between backdrop and participant. Hong Kong isn't just a setting; it's a vibrant, nervous character facing its own uncertain future, mirrored in the lives unfolding within it. You can almost feel the humidity, smell the street food mingling with exhaust fumes, sense the collective exhale of a million untold stories.

Borrowed Time, Captured Moments

At the heart of this atmospheric swirl is John, played by Jeremy Irons. A British journalist residing in Hong Kong, he learns he has terminal leukemia with only months left to live – months that coincide precisely with the territory's final days under British rule. It’s a parallel that could feel heavy-handed, but Irons invests John with a weary grace and detached curiosity that avoids melodrama. His response isn't despair, but an urgent, almost compulsive need to document the city and its people, primarily through his video camera. He becomes a voyeur of endings – his own, and the city’s. We see much of Hong Kong through his lens, fragmented, raw, sometimes intrusive. It raises questions, doesn't it? About the nature of observation, about capturing life versus living it, about what remains when the moment passes. Irons, always compelling, embodies this fragile observer role perfectly, his familiar voice carrying the weight of unspoken goodbyes.

Faces in the Crowd

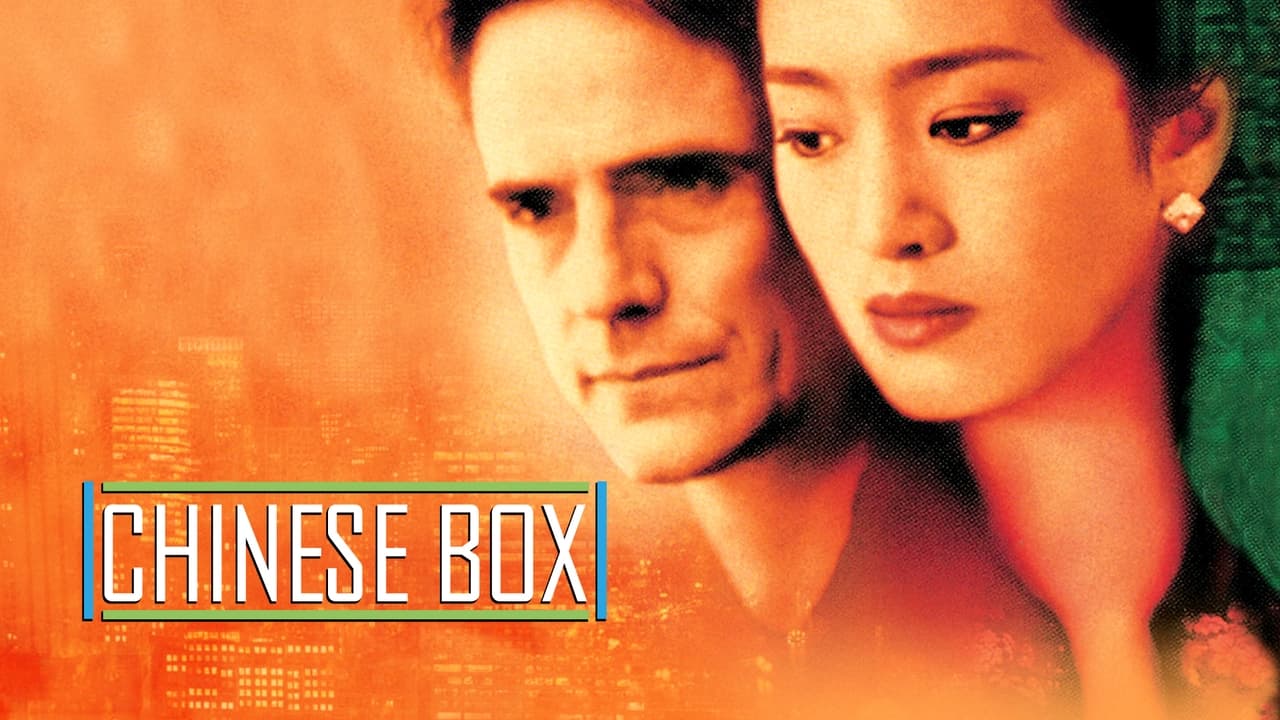

John’s gaze, and ours, is drawn to two women who represent different facets of Hong Kong's complex identity. Vivian, portrayed with captivating poise by the luminous Gong Li, is a sophisticated former mainlander caught between her past, her ambiguous relationship with a powerful local businessman (played by Hong Kong cinema stalwart Michael Hui), and her undeniable connection to John. Their scenes together are steeped in a quiet longing and the sadness of impossible timing. Gong Li conveys Vivian's guarded vulnerability beautifully, a woman navigating treacherous social and emotional currents.

Then there's Jean, the enigmatic street hustler played by the magnetic Maggie Cheung. With her scarred face and fiercely independent spirit, Jean becomes John’s unlikely muse and confidante. It’s a relatively small role, yet Cheung makes an indelible impression. Reportedly a later addition to the cast, she brings a raw, street-level energy that contrasts sharply with Vivian’s elegance. Her interactions with John possess a strange tenderness, two damaged souls finding a brief, unconventional solace amidst the city's flux. Rubén Blades, musician and actor, also adds a warm presence as John's photographer friend, Jim, offering another perspective on capturing the fleeting moment.

The Beauty in Imperfection

Chinese Box isn't a film driven by intricate plotting. Its script, co-written by an intriguing trio – Jean-Claude Carrière (a frequent collaborator with surrealist master Luis Buñuel), Larry Gross (48 Hrs.), and novelist Paul Theroux – feels more like a collection of resonant encounters and observations than a tightly structured narrative. Director Wayne Wang himself acknowledged struggles in finding the perfect shape for the story, and sometimes this shows. The pacing can feel languid, certain threads drift, and the film occasionally leans into its own melancholic ambiguity a bit too heavily.

Yet, this looseness somehow feels appropriate. It mirrors the uncertainty of the characters and the city itself. It’s a film that invites contemplation rather than demanding conclusion. Wang’s direction emphasizes mood over mechanics, using Christopher Doyle’s (often Wong Kar-wai's cinematographer) evocative camerawork (though Vilko Filač is credited as DP) to capture the neon glow, the cramped spaces, the faces in the teeming crowds. The result is less a story told than an experience felt.

Legacy of a Glance

Watching Chinese Box today offers a unique kind of nostalgia – not just for the era of VHS rentals, but for a specific historical precipice. It captured a Hong Kong that was about to transform irrevocably. The film doesn’t offer easy answers about identity, belonging, or the relentless march of time, but it frames the questions with poignant beauty. It’s a snapshot, intentionally imperfect, of lives caught in the slipstream of history. Does its narrative ambiguity sometimes frustrate? Perhaps. But does its atmosphere, its performances, and its haunting sense of place stay with you? Absolutely. It’s a film that rewards patience, asking you to simply exist within its world for a while, much like John does, camera in hand, watching the final moments tick away.

Rating: 7/10

This rating reflects the film's undeniable atmospheric power, its thoughtful performances (especially from Irons, Gong Li, and the unforgettable Maggie Cheung), and its unique value as a time capsule. It captures the specific mood and tension of the Hong Kong handover with rare intimacy. However, its sometimes meandering narrative and deliberate ambiguity prevent it from reaching the heights of a truly flawless classic, keeping it slightly shy of masterpiece territory but firmly in the realm of deeply worthwhile viewing for those who appreciate mood and character over conventional plot.

Final Thought: Like a fading photograph, Chinese Box holds a specific, bittersweet moment in time, leaving you pondering the echoes of history in the lives we briefly touch.