There's a certain quality to Dieter Dengler's eyes, a persistent spark even as he recounts horrors that would extinguish most spirits. Watching Werner Herzog's 1997 documentary Little Dieter Needs to Fly again, decades after first encountering it perhaps late one night on television or tucked away in the less-visited section of the video store, that spark is what remains most vivid. It’s the unnerving juxtaposition of a man radiating an almost buoyant resilience while detailing experiences that flirt with the unimaginable depths of human suffering.

The Dreamer and the Nightmare

Herzog, ever the cinematic explorer of extreme landscapes both external and internal, introduces us to Dengler not just as a survivor, but as a lifelong dreamer. We learn of his childhood in a war-torn Germany, looking up at Allied pilots and knowing, with absolute certainty, that he needed to fly. This almost naive, pure ambition propelled him across the Atlantic to America, eventually earning him his wings as a US Navy pilot. It’s a classic immigrant success story, painted with Dengler's infectious optimism. But dreams, as Herzog often reminds us, can curdle into nightmares. Dengler’s came true in the skies over Laos during the Vietnam War, where his plane was shot down on his very first combat mission.

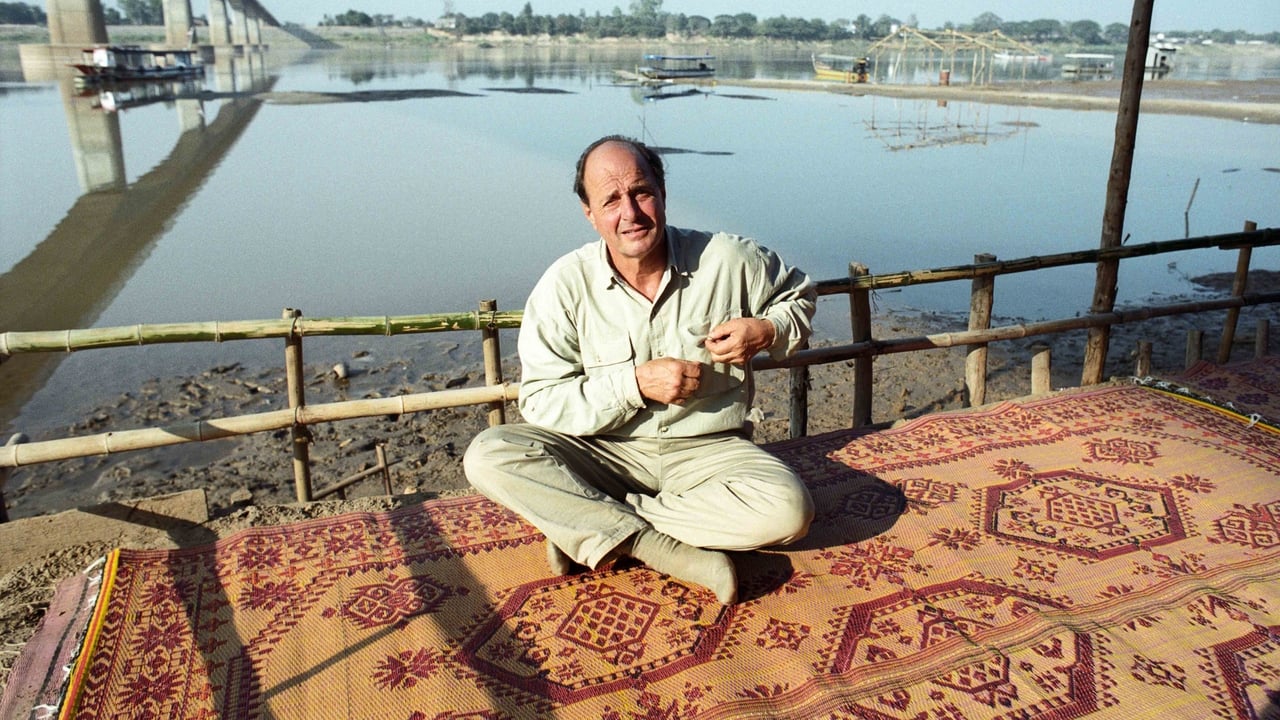

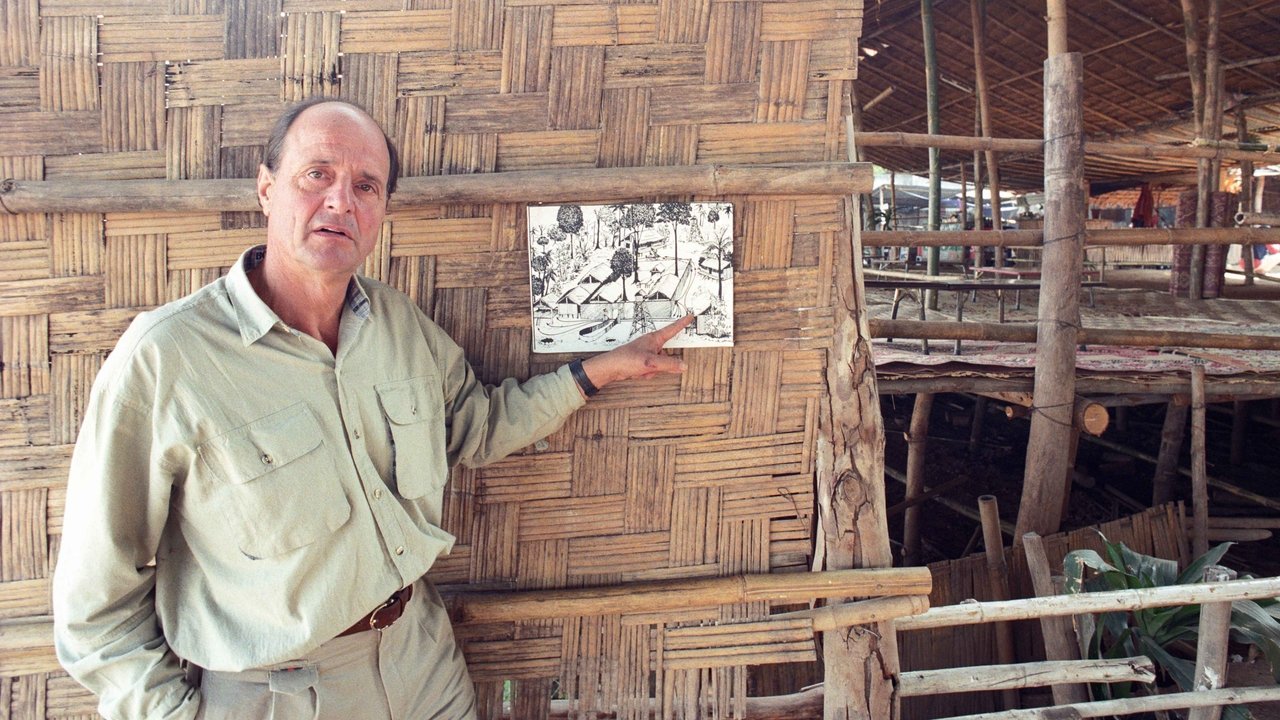

What follows is the core of the film: Dengler’s harrowing account of capture, starvation, torture, and eventual escape from a Pathet Lao prison camp. Herzog doesn't just let Dengler talk; in a move both compelling and ethically complex, he takes Dengler back. Back to the humid jungles of Laos and Thailand (standing in for the actual locations), back to reenact moments of profound trauma. We see Dengler, guided by Herzog’s calm, almost hypnotic narration, demonstrate how he was tied, how he picked locks, how he hid. Is this exploitation? Therapy? A uniquely Herzogian form of cinematic truth-seeking? It’s undeniably powerful, blurring the lines between memory and performance, testimony and spectacle. Watching Dengler demonstrate his meticulous escape preparations using skills learned from his clockmaker grandfather feels less like a documentary detail and more like witnessing the very mechanics of survival itself.

Herzog's Method, Dengler's Truth

Werner Herzog, a director known for films like Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) and Fitzcarraldo (1982) – tales often featuring obsessive protagonists battling overwhelming nature or their own psyches – finds a perfect subject in Dengler. Herzog's presence isn't neutral; his distinctive voiceover guides our perception, framing Dengler's story within his own thematic preoccupations with chaos, endurance, and the thin veneer of civilization. He seems genuinely fascinated, even awed, by Dengler's ability to have stared into the abyss and returned, not broken, but somehow… still Dieter.

One fascinating aspect Herzog brings out is the lingering impact of the trauma. Dengler, living comfortably in California years later, reveals cabinets packed floor-to-ceiling with hoarded food, a visceral manifestation of the starvation he endured. He compulsively opens and closes doors, a habit born from imprisonment. These aren't just anecdotes; they are windows into the deep, permanent shifts that extreme experience carves into a person. It’s a testament to Dengler’s openness and Herzog’s skill as an interviewer that these vulnerabilities are shared with such candor.

Beyond the Reenactment

While the staged sequences are the film's most discussed element, the power also lies in Dengler simply telling his story. His face, animated and expressive, carries the weight of memory. There's a chilling moment when he describes the casual cruelty of his captors, or the desperation that led him and fellow prisoner Duane W. Martin to make their incredibly risky escape attempt. Dengler doesn't perform grief or horror; he embodies the memory of it, and that authenticity is more affecting than any dramatic recreation could be. Herzog later revisited this story with the fictionalized Rescue Dawn (2006), starring Christian Bale. While a solid film, comparing it to Little Dieter highlights the raw, unmediated power of hearing the story directly from the man who lived it.

The production itself reflects a certain practicality common in documentary filmmaking, yet Herzog’s eye ensures it never feels merely functional. The way he frames Dengler against vast landscapes or within the confines of his own home speaks volumes. It wasn't a blockbuster, originally made for German television (ZDF), but its impact far outweighs its budget. It’s a film that likely found its audience gradually, through word-of-mouth, festival circuits, and yes, those trusty VHS tapes passed between enthusiasts.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's profound impact and unique execution. Little Dieter Needs to Fly is a masterful, albeit sometimes uncomfortable, documentary experience. Herzog's signature style perfectly complements Dengler's astonishing story of survival, creating a portrait of resilience that is both deeply personal and universally resonant. The ethical questions surrounding the reenactments linger, but they don't overshadow the raw truth and power emanating from Dieter Dengler himself. It earns its high rating through sheer force of personality – Dengler's – and the unflinching, curious gaze of its director.

What stays with you long after the credits roll isn't just the horror, but the enduring image of that spark in Dieter's eyes – the unyielding need, not just to fly, but to live.