It’s difficult to know where to begin with Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah. There’s the sheer, daunting length – over nine hours, usually spread across multiple VHS tapes back in the day, demanding a commitment far beyond the usual Friday night rental. There’s the subject matter, the Holocaust, approached with an unflinching directness that avoids easy sentiment or familiar historical shortcuts. And then there’s the deliberate, almost radical filmmaking choice that defines it: the complete absence of archival footage. No grainy newsreels, no photographs of the atrocities. Only the present, haunted by the past.

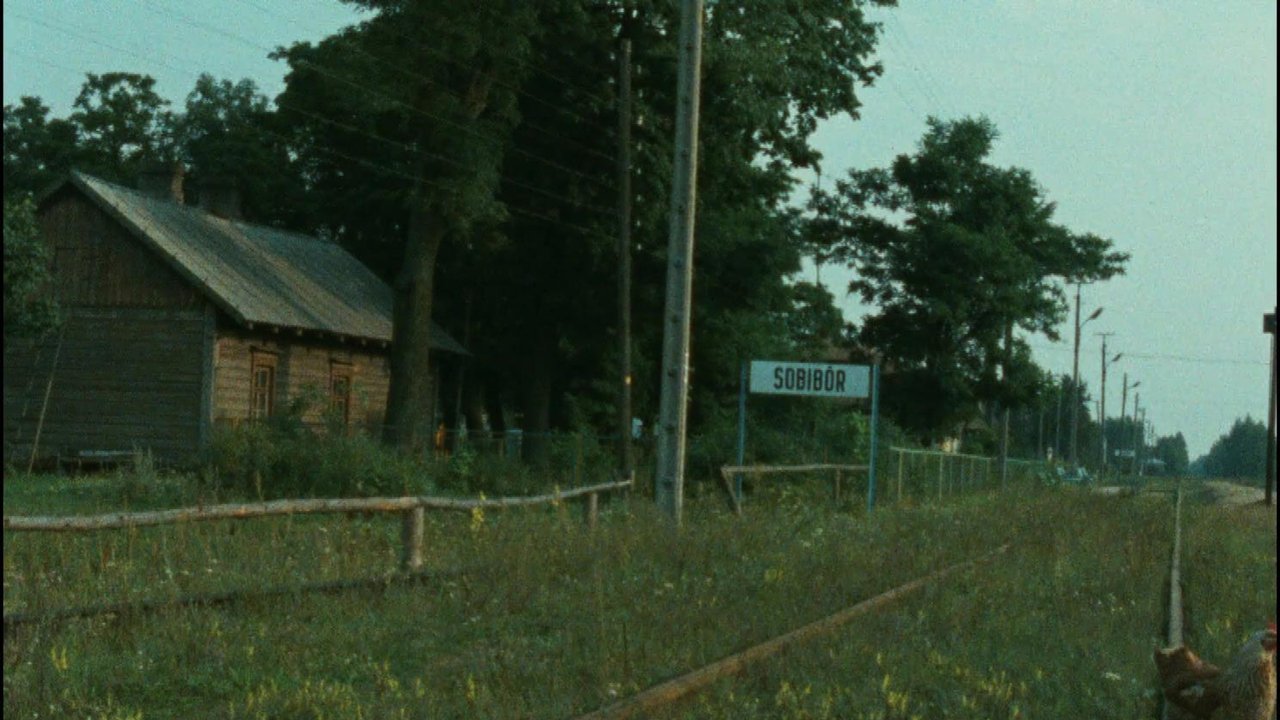

Lanzmann, who dedicated an astonishing eleven years of his life to this project (from 1974 to 1985), wasn't interested in retelling history through old images. He wanted to excavate memory itself. He filmed over 350 hours of testimony, traveling across 14 countries, seeking out survivors, perpetrators, and bystanders, placing them often in the very locations where history unfolded – the tranquil Polish villages, the overgrown sites of extermination camps like Chelmno, Treblinka, Auschwitz-Birkenau. The effect is profoundly unsettling. Seeing a survivor recount unimaginable horrors while standing in a sun-dappled forest, or a former SS officer describe bureaucratic murder with chilling detachment, forces a confrontation with the past that feels immediate, visceral, and inescapable.

Bearing Witness in the Present Tense

What Shoah captures so powerfully is the persistence of memory and the chilling banality that often surrounded industrialized evil. Lanzmann’s interview technique is patient, persistent, sometimes bordering on confrontational. He doesn't shy away from difficult questions, pushing his subjects to recall details they might prefer to forget. We see Simon Srebnik, one of only two survivors of Chelmno, return to the village where he was forced to sing for the Nazis as a boy, his haunted eyes scanning the familiar, yet irrevocably changed, landscape. We listen to Abraham Bomba, a barber forced to cut women's hair before they entered the gas chambers at Treblinka, break down while describing the unimaginable inside a modern barbershop. These moments aren't staged for drama; they are the raw, unfiltered eruption of trauma into the present day.

The film’s structure isn't chronological in a traditional sense. It weaves together these testimonies, moving geographically and thematically, building a devastating mosaic of the 'Final Solution'. Lanzmann often acts as the viewer's guide, his presence felt, his questions driving the inquiry. The use of translators, often visible and audible, becomes part of the texture, highlighting the distances – linguistic, temporal, experiential – that must be bridged.

The Monumental Task

Bringing Shoah to fruition was a Herculean effort, far beyond typical filmmaking challenges. Securing interviews, particularly with former Nazis (some filmed secretly with hidden cameras, raising ethical questions that Lanzmann staunchly defended as necessary), required immense persistence and, reportedly, considerable financial resources raised from various sources over the years. Lanzmann wasn't just documenting; he was actively investigating, piecing together the mechanics of extermination through the words of those who were there. The sheer logistics of filming across continents, coordinating translators, and managing the immense volume of footage represent a staggering feat of dedication. It wasn’t a film made about the Holocaust; in many ways, it feels like a film wrenched from its shadow.

Watching it back in the era of VHS, often requiring multiple tapes rented perhaps over a weekend, was an undertaking. It wasn't casual viewing. It demanded attention, patience, and emotional fortitude. There were no action sequences, no star turns, just the relentless, accumulating weight of testimony. It wasn't escapism; it was immersion in a reality many would rather avoid. Yet, its power lies precisely in this refusal to look away, its insistence on listening.

Why It Endures

Decades after its release, Shoah remains a towering, essential work. It bypasses the mediation of historical representation to connect us directly with the human experience of the Holocaust. Lanzmann’s choice to focus solely on testimony and present-day locations forces us to grapple with the enduring presence of the past, the way landscapes hold memory, and the chilling ways ordinary people participated in, or were victims of, extraordinary evil. It asks profound questions about memory, denial, and the responsibility of bearing witness. How do we confront such history without the buffer of familiar imagery? What does it mean to listen, truly listen, to these voices?

Its influence on documentary filmmaking is undeniable, though its sui generis nature makes it difficult to imitate. It stands as a monument, not just to the victims, but to the power of cinema to confront the darkest chapters of human history with rigor, artistry, and unwavering moral clarity.

Rating: 10/10

Assigning a numerical rating to Shoah feels almost inadequate, reducing a profound historical and cinematic achievement to a simple score. However, its importance, its meticulous craft, its devastating impact, and its unwavering commitment to bearing witness make it an undeniable masterpiece. The 10/10 reflects its status as an essential, unparalleled work of testimony and remembrance, a film whose gravity and significance haven't diminished one iota since those hefty VHS cassettes first landed on rental shelves. It’s not a film you ‘enjoy,’ but one you experience, absorb, and carry with you.

What lingers most, perhaps, is the quiet landscape – a field, a river, a railway siding – suddenly charged with the weight of unspoken history, demanding that we never forget.