It arrives like a whisper from a dusty archive, a rumour of cinematic revolution lost to time. Forgotten Silver, presented initially on New Zealand television in 1995 before its wider 1997 release, feels like stumbling upon a secret history, the kind cinephiles dream of uncovering. It tells the staggering story of Colin McKenzie, a pioneering Kiwi filmmaker who, decades before the acknowledged masters, supposedly invented colour film, synchronised sound, and even the tracking shot, culminating in a biblical epic, Salome, filmed deep in the New Zealand jungle. The initial feeling watching it, especially if you encountered it without context back in the day, wasn't just intrigue; it was a profound sense of discovery, a thrilling rewrite of film history.

The Genius Who Never Was

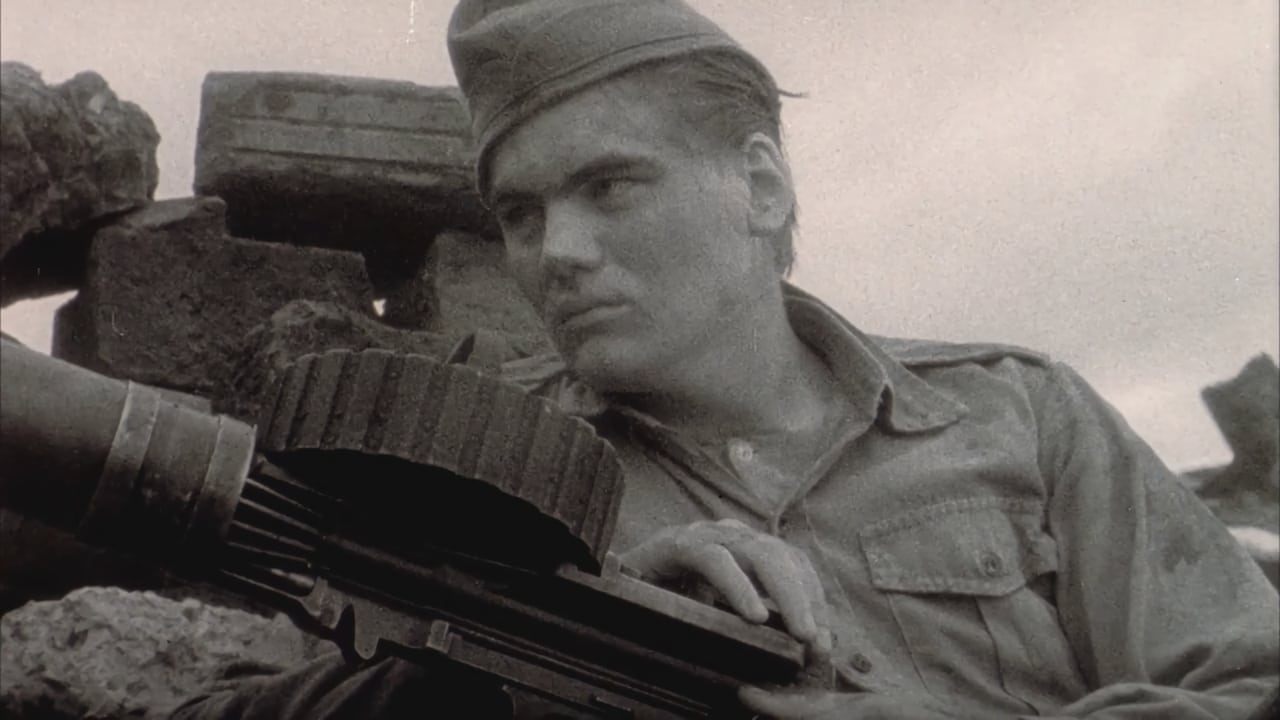

Directed and presented by a pre-Lord of the Rings Peter Jackson and Costa Botes, the film unfolds with the earnest conviction of a genuine historical documentary. Jackson, playing himself with infectious enthusiasm, guides us through McKenzie’s alleged life and work, piecing together fragments of astonishingly innovative (and convincingly aged) film reels apparently unearthed in an old shed. We hear from historians, family members, and even notable film figures like critic Leonard Maltin, actor Sam Neill, and Miramax head Harvey Weinstein (a presence that certainly lands differently now), all seemingly validating McKenzie's genius and tragic obscurity. The level of detail is extraordinary – from the primitive, hand-cranked cameras to the mock-ups of early colour processes ("nitrate needing poppy juice," wasn't that the claim?), every element feels meticulously researched and authentic.

Crafting a Legend

The brilliance of Forgotten Silver lies entirely in its masterful deception. Colin McKenzie, of course, never existed. The entire narrative, the "found footage," the historical connections – it's all an elaborate, affectionate hoax. What makes it truly remarkable isn't just the audacity of the premise, but the sheer craft involved. Jackson and Botes didn't just tell a tall tale; they showed it, painstakingly recreating the look and feel of early 20th-century cinema. They reportedly achieved the aged look by dragging film through gravel, scratching negatives, and employing other lo-fi techniques that perfectly mimicked the wear and tear of decades. The "Salome" footage, with its surprisingly vast (miniature) sets and ambitious scope, is a particular highlight, a convincing pastiche of silent-era epics. It’s a testament to Jackson’s already formidable skills in visual storytelling and his clear, deep-seated love for cinema history, even as he playfully rewrites it. Remember, this was made for roughly NZ$1 million – a shoestring budget even then, forcing incredible ingenuity.

Why the Hoax Resonates

The initial broadcast in New Zealand famously caused a stir, with many viewers completely taken in, leading to subsequent outrage from some when the truth was revealed. But why did it work so well? Partly, it's the conviction of the presentation. Jackson is a natural on camera, his passion infectious. Leonard Maltin's presence, in particular, lent enormous credibility; seeing a respected film historian earnestly discussing McKenzie’s supposed breakthroughs felt like irrefutable proof. There’s also something inherently appealing about the idea of the unsung genius, the forgotten pioneer. We want to believe that history might hold such secrets, that giants could have walked the earth (or, in this case, the New Zealand bush) unnoticed. The film taps into that romantic notion, the mythology surrounding invention and discovery. Doesn't it speak volumes about our relationship with history and the moving image, how easily we can accept a well-told story as fact?

Beyond the cleverness, there’s a genuine warmth here. The film isn’t mocking film history or documentary conventions; it’s celebrating them through imitation. It’s a love letter to the pioneers, both real and imagined, and to the magic of filmmaking itself. Watching it now, knowing Jackson’s later trajectory – directing the actual most ambitious epics imaginable – adds another layer. You can see the seeds of Middle-earth in the ambitious (faked) scope of McKenzie’s Salome, the same boundless imagination and technical ingenuity at play, albeit on a vastly different scale. It feels like a vital stepping stone, showcasing the creative spirit that would soon conquer Hollywood.

A Treasure Found, Then Understood

Forgotten Silver remains a unique and delightful entry in the mockumentary genre, standing shoulder-to-shoulder with classics like This Is Spinal Tap (1984) but with its own distinct flavour – less satirical, more affectionately inventive. It plays with our perceptions, challenges our assumptions about historical narratives, and ultimately leaves you marvelling at the filmmakers' skill and wit. It’s a film that rewards knowing the secret, allowing you to appreciate the intricate construction of the illusion. Revisiting it feels like being in on a wonderful, elaborate joke crafted by people who simply adore movies.

---

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's near-perfect execution as a mockumentary. Its cleverness, technical skill in recreating historical footage, convincing performances (especially by the non-actors playing themselves), and affectionate tone make it a standout. The sheer audacity combined with the loving attention to detail elevates it beyond a simple prank into a fascinating commentary on film history and belief. It only narrowly misses a perfect score perhaps because its power relies heavily on the initial surprise or subsequent appreciation of the hoax, but its craft remains undeniable.

Final Thought: What lingers most after watching Forgotten Silver isn't just the memory of a clever hoax, but a deeper appreciation for the power of cinema to construct reality, and perhaps, a quiet nod to the countless real unsung pioneers whose stories might still be waiting in the archives.