There's a certain kind of listlessness that permeates the humid air of South Florida, a sense of being stuck while dreaming of escape. Few films capture this peculiar inertia quite like Kelly Reichardt's 1995 debut, River of Grass. It arrived in a decade often defined by ironic detachment and flashy indie crime capers, yet Reichardt offered something else entirely: a sun-bleached, aimless journey going absolutely nowhere, fast. Watching it again now, perhaps on a worn-out tape dug from a dusty box, feels less like revisiting a conventional thriller and more like recalling a half-forgotten, hazy dream of suburban dissatisfaction.

Somewhere South of Trouble

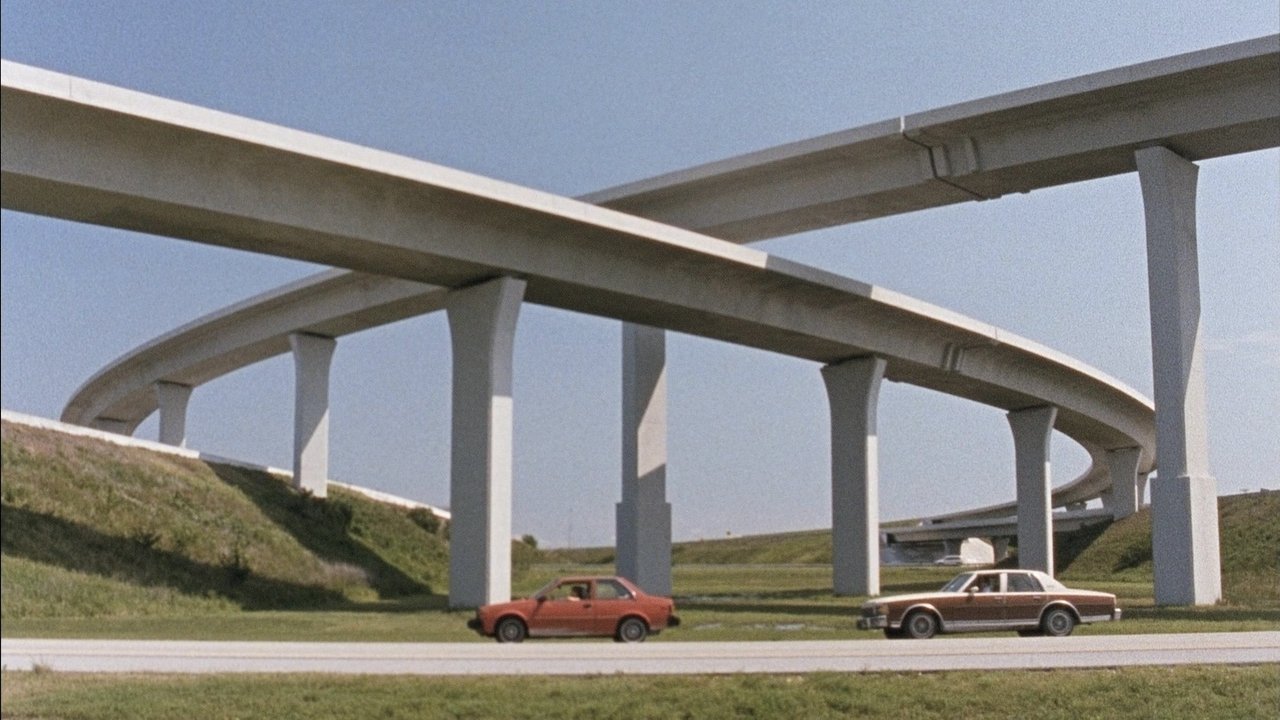

The premise feels almost like a parody of a lovers-on-the-run narrative. Cozy (Lisa Bowman), a profoundly bored housewife and mother trapped in a passionless marriage, yearns for something – anything – different. She finds a potential spark in Lee Ray Harold (Larry Fessenden, a stalwart of independent cinema himself, known for his Glass Eye Pix productions and roles in films like Habit (1997)), an equally directionless local layabout. A drunken night, a misplaced handgun belonging to Cozy's detective father (Dick Russell), and a perceived gunshot lead them to believe they've accidentally killed someone by a swimming pool. The logical next step? Hit the road, become outlaws. The problem? They're broke, incompetent, and fundamentally lack the conviction to actually leave. Their "flight" becomes less a desperate escape and more an extended, awkward detour through the familiar landscapes of strip malls and highways near their homes.

The Anti-Thriller Aesthetic

What makes River of Grass stand out, especially looking back from the VHS era, is Reichardt's deliberate refusal to play by genre rules. There are no thrilling chases, no witty banter between charismatic criminals, no cathartic showdowns. Instead, the film luxuriates in the mundane moments between the non-events. Reichardt, who also co-wrote the script, focuses on the textures of boredom: the drone of the radio, the glare of the sun on asphalt, the awkward silences between two people who don't really know what they're doing or why. Shot on grainy 16mm, the film possesses a visual texture that feels perfectly suited to the low-fi charm of a well-loved VHS tape. The look is raw, unpolished, capturing the sticky heat and washed-out colours of Dade and Broward counties, Florida – areas Reichardt herself grew up in, lending an undeniable authenticity to the film's sense of place. It’s fascinating to see the seeds of her later, more celebrated observational style (seen in films like Wendy and Lucy (2008) or First Cow (2019)) already present in this first feature.

Portraits in Aimlessness

The performances are key to the film’s peculiar power. Lisa Bowman, in a role that feels remarkably unvarnished, embodies Cozy's ennui perfectly. She’s not glamorous or particularly sympathetic, but her quiet desperation and naive belief that something better must exist feels painfully real. You see the weight of unmet expectations settling on her shoulders. Larry Fessenden avoids any hint of outlaw cool as Lee Ray. He’s clumsy, slightly pathetic, driven more by impulse than malice. There’s a vulnerability beneath his feckless exterior that makes his inability to escape his circumstances almost poignant. Together, they’re less Bonnie and Clyde and more two lost souls bumping into each other in the vast, indifferent landscape Marjory Stoneman Douglas famously called the "River of Grass" – the Everglades, a place that, like their lives, seems sprawling yet confining.

From Shoestring to Cult Status

It’s almost a small miracle River of Grass exists at all. Reportedly scraped together for somewhere between $40,000 and $50,000 (a truly minuscule sum even then!), its production was fraught with the challenges typical of ultra-low-budget filmmaking. Its journey wasn't easy after completion either; debuting at Sundance in 1994, it struggled to find significant distribution. For many of us who saw it back in the day, it was likely discovered languishing in the indie or drama section of the local video store, a curiosity piece rather than a buzzy new release. Its slow burn to cult appreciation, culminating in a beautiful restoration by Oscilloscope Laboratories years later, speaks volumes about its unique, resonant qualities. It wasn't trying to be the next Pulp Fiction; it was doing its own quiet, strange thing, and eventually, people noticed. The title itself, drawn from that evocative description of the Everglades, perfectly mirrors the characters' predicament – seemingly vast and open, yet shallow, slow-moving, and difficult to navigate.

The Lingering Haze

River of Grass isn't a film that provides easy answers or conventional satisfaction. It captures a very specific feeling – the suffocating weight of unrealized dreams and the paralyzing fear that maybe this dead-end road is all there is. It’s a mood piece disguised as a crime story, a sun-drenched noir where the greatest mystery is how to simply get moving. Its deliberate pacing and lack of traditional narrative propulsion might test some viewers, but for those attuned to its frequency, it offers a strangely compelling portrait of American restlessness. Does the awkwardness of their non-escape resonate with those moments we've all felt stuck, dreaming of elsewhere but rooted to the spot?

Rating: 7/10

This rating reflects River of Grass's distinct artistic vision and its success in capturing a specific, potent mood. Reichardt's nascent talent is undeniable, and the performances from Bowman and Fessenden feel authentic in their awkwardness. The film’s low-budget origins contribute to its unique charm and atmosphere, making it a standout piece of 90s independent cinema. However, its intentionally slow pace and anti-climactic nature mean it’s not a journey everyone will want to take, keeping it from higher marks reserved for more universally accessible classics. It earns its points through sheer atmospheric integrity and thematic resonance.

It’s a film that lingers like the drone of cicadas on a hot afternoon – a quiet testament to the fact that sometimes, the most terrifying journey is the one that never truly begins.