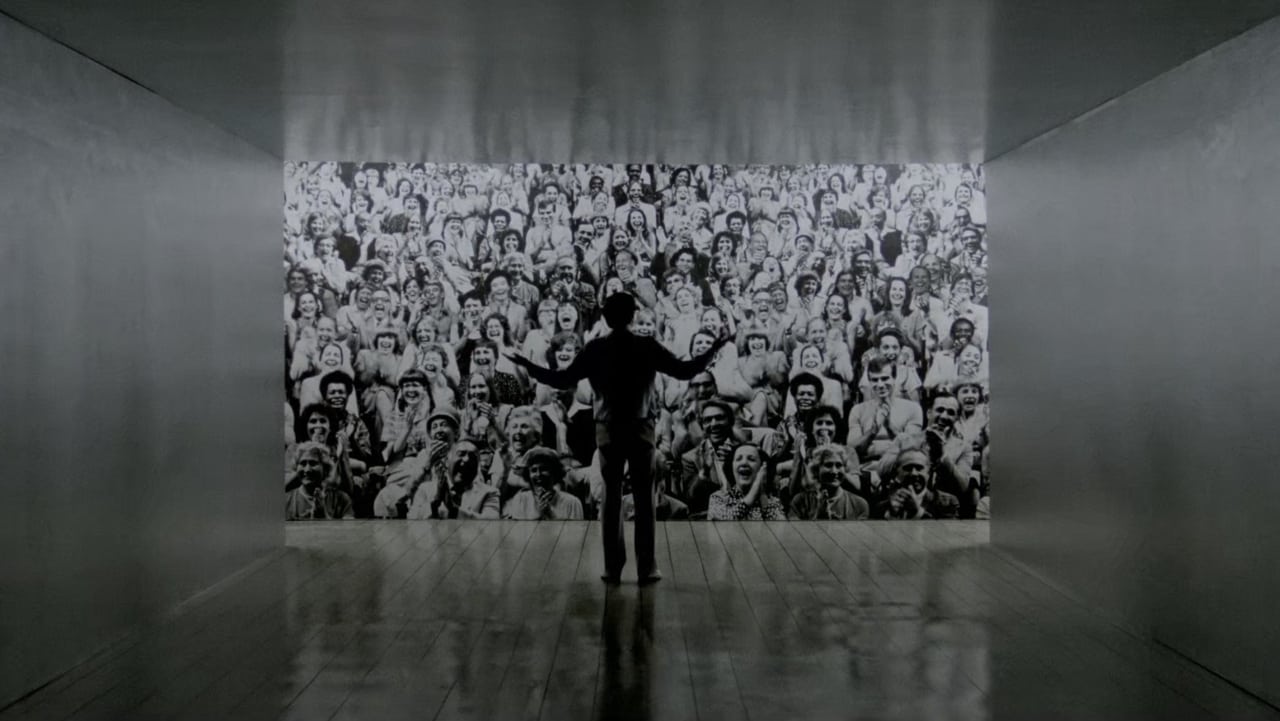

That persistent image: Rupert Pupkin, alone in his meticulously recreated talk-show set in his mother's basement, performing his excruciatingly unfunny monologue to life-sized cardboard cutouts of Jerry Langford and Liza Minnelli. There’s something so specific about the memory of seeing that scene on a rented VHS tape, the slightly fuzzy picture on a CRT somehow amplifying the profound awkwardness. It’s funny, undeniably, but it's a laughter caught in the throat, laced with a discomfort that lingers long after the tape rewound. Martin Scorsese's The King of Comedy (1982) wasn't the movie many expected back then, and perhaps that's precisely why it remains such a fascinating, unnerving watch today.

An Uncomfortable Close-Up

Forget the kinetic energy of Mean Streets (1973) or the operatic sweep of Raging Bull (1980). Here, Scorsese, working from a sharp, bleak script by Paul D. Zimmerman, turns his camera inward, creating a film that feels claustrophobic and deliberately paced. We are trapped with Rupert Pupkin, played with terrifying commitment by Robert De Niro, a painfully inept aspiring comedian whose ambition massively outweighs his talent. Pupkin isn't just starstruck by late-night legend Jerry Langford; he believes, with unwavering delusion, that a single appearance on Langford's show is his destiny, the only thing separating him from the adoration he craves. His methods for achieving this are increasingly unhinged, blurring the lines between fan, pest, and genuine menace.

De Niro's Disquieting Disappearance

De Niro’s transformation into Pupkin is astonishing, precisely because it lacks the explosive physicality we often associate with his iconic roles. Pupkin is all surface pleasantries barely masking a simmering, inappropriate intensity. His smiles don't reach his eyes, his polyester suits seem permanently stiff, and his belief in his own destined stardom is absolute, impervious to rejection or reality. It's a performance built on awkward pauses, misplaced confidence, and a chilling lack of self-awareness. De Niro reportedly used anti-Semitic slurs (off-camera) towards Jerry Lewis before their scenes to generate genuine animosity, a Method technique that speaks to the uncomfortable reality they were trying to capture. Watching him, you don't see Travis Bickle's rage or Jake LaMotta's brute force; you see a different, quieter, and perhaps more insidious kind of pathology – the desperate, hollow need for external validation.

The King in Exile

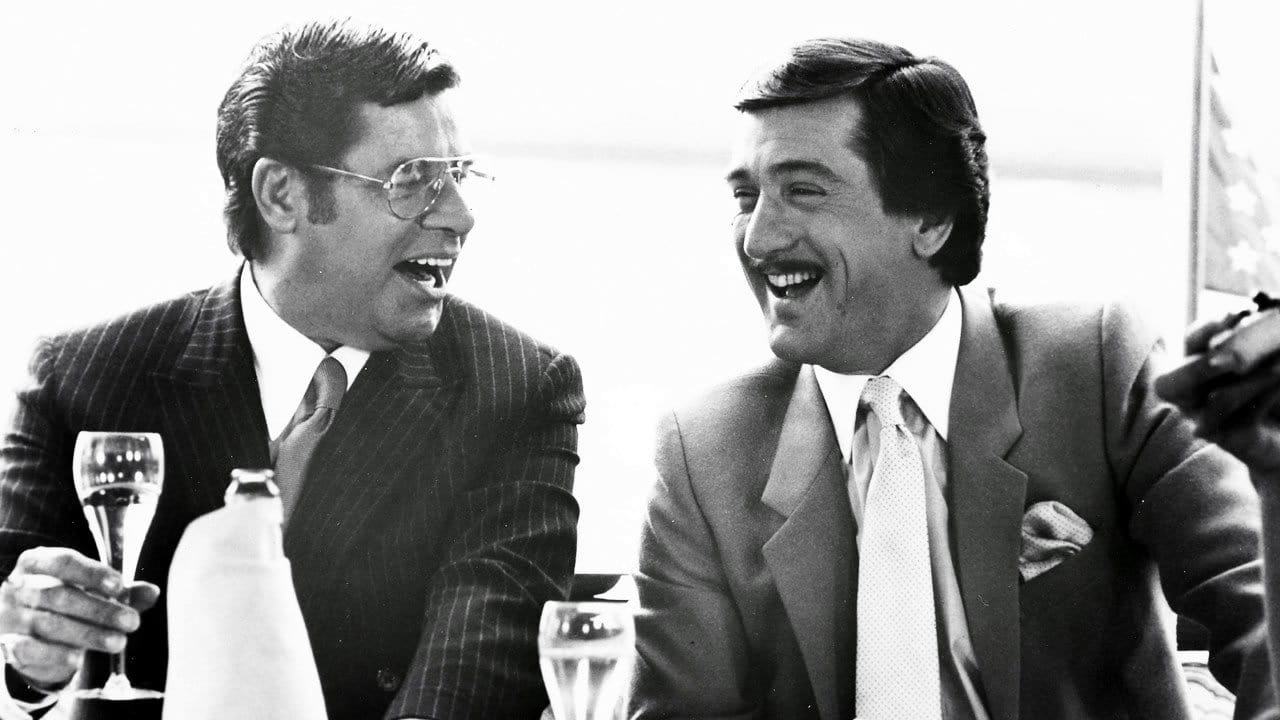

The casting of comedy icon Jerry Lewis as the weary, harassed Jerry Langford was a stroke of genius. Lewis, known for his manic physical comedy and telethon ubiquity, plays Langford with a profound exhaustion. He's not a villain; he's a man trapped by his own fame, besieged by the very adoration that sustains him. There’s a scene where Langford is simply walking down the street, trying to remain anonymous, accosted by a fan wanting him to speak to her sick relative on the phone. Lewis conveys the crushing weight of constant demand with heartbreaking subtlety. He’s the straight man not just to Pupkin’s delusion, but to the absurdity of modern celebrity itself. The tension between him and De Niro feels palpable, a result perhaps not just of acting, but of the contrasting personalities and reported on-set friction. Lewis delivers a remarkably restrained, dramatic performance that anchors the film's uncomfortable realism.

Partners in Cringe

Rounding out the central trio is Sandra Bernhard as Masha, another obsessed fan who becomes Pupkin's erratic accomplice. If Pupkin's delusion is tightly controlled, Masha's is pure chaos. Bernhard crackles with a manic, unpredictable energy that is both hilarious and genuinely alarming. Her infamous scene where she "seduces" a duct-taped Langford is a masterclass in pushing boundaries, toeing the line between comedy and horror. Together, Pupkin and Masha represent different facets of the same corrosive desire for proximity to fame, willing to cross any line for a reflected glow.

Fame's Funhouse Mirror

Released in 1982, The King of Comedy felt strangely out of step. It wasn't a feel-good comedy, nor was it a typical Scorsese crime drama. It bombed at the box office, pulling in a mere $2.5 million against a $19 million budget (that's roughly $7.8 million gross against $59 million adjusted for inflation – a definite financial disappointment). Critics were divided. Some recognized its brilliance, while others found it too grating, too unpleasant. I remember renting it, perhaps misled by the title and De Niro’s presence, expecting something… different. What I got was a film that burrowed under my skin.

Yet, watching it now, The King of Comedy feels startlingly prescient. Decades before social media influencers, reality TV obsession, and the quest for viral fame, Scorsese and Zimmerman crafted a chilling portrait of celebrity worship curdling into dangerous entitlement. The film asks uncomfortable questions: Where does fandom end and pathology begin? What happens when the lines between the performer and the audience dissolve entirely? Doesn't Pupkin's desperate, mediated existence feel eerily familiar in our hyper-connected world? The film's controversial ending, which Scorsese insists is real and not Pupkin's fantasy, delivers the ultimate cynical punchline about the nature of notoriety in modern media.

Why It Holds Up

The King of Comedy isn't an easy watch. It substitutes suspense with squirm-inducing awkwardness, and catharsis with a lingering sense of unease. Yet, its power lies in its unflinching honesty. Scorsese’s direction is masterful in its restraint, forcing us to sit with the characters in their uncomfortable silences. The performances, particularly from De Niro and Lewis, are career highlights, brave departures that reveal unsettling truths. It’s a film that perhaps resonates even more deeply now, in an age saturated with the very celebrity culture it dissected so precisely. It might not have been the comedy king audiences wanted in '82, but its reign as a cult classic and a disturbingly relevant satire is undisputed. The influence is clear in later films exploring similar themes, most notably Joker (2019).

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's masterful execution, its powerhouse performances, and its chillingly prescient themes. It’s docked a single point only because its deliberately abrasive nature and slow burn might not connect with absolutely everyone, but its artistic merit and cultural resonance are undeniable. It's a vital piece of 80s cinema, even if it took decades for its brilliance to be widely recognized.

What lingers most after the static fades isn't the bad jokes, but the chilling emptiness behind Pupkin's eyes – a void that reflects a disturbingly familiar hunger in our modern obsession with being seen.