Okay, let's dim the lights, maybe pour something strong, because tonight we're diving into a film that absolutely refused to be ignored back in its day. Slipping the hefty VHS cassette of Peter Greenaway's The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989) into the VCR always felt like an act of transgression, didn't it? It wasn't your typical Friday night rental fare. There was a buzz around this one, whispers of its shocking content, its art-house pedigree, and that infamous X rating it initially received in the States (before being cannily released unrated). It promised something beautiful, brutal, and utterly unforgettable. And frankly, it delivered on all counts.

A Feast for the Eyes, A Nightmare for the Soul

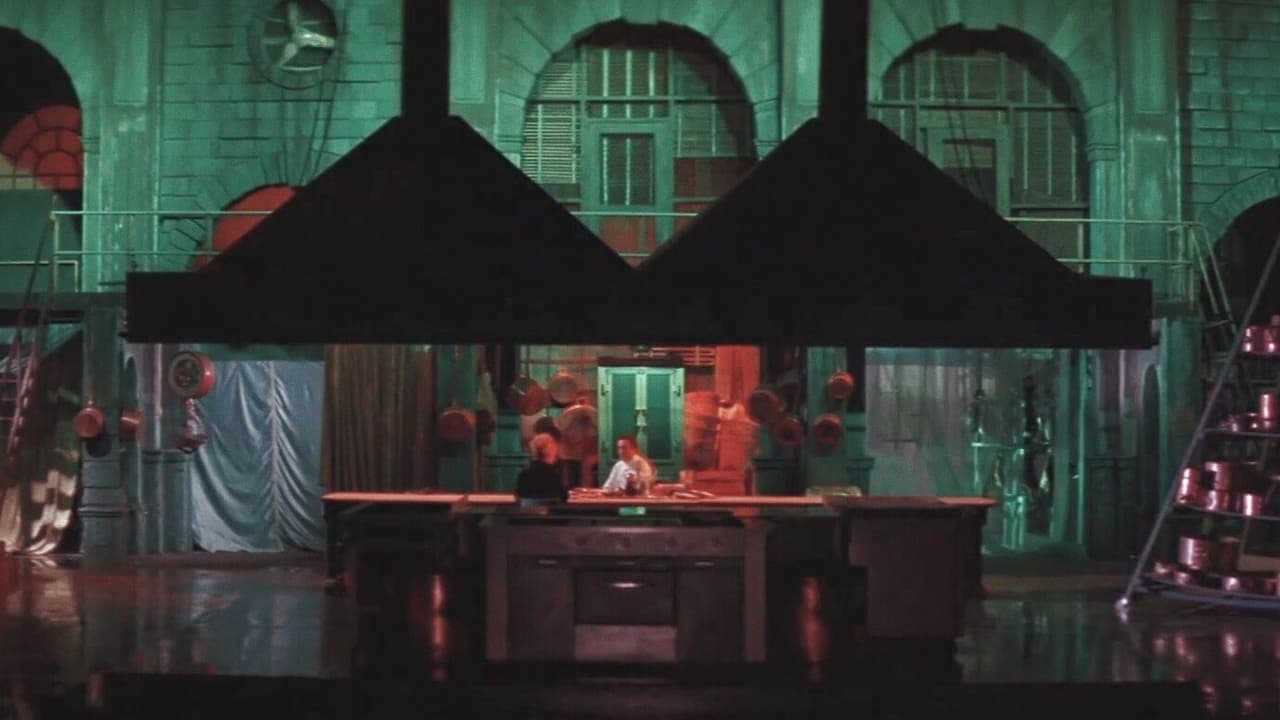

From the moment the film opens, you're plunged into the oppressive, hyper-stylized world of Le Hollandais, the opulent restaurant owned by the monstrous gangster Albert Spica. Greenaway, ever the formalist painter translating his vision to celluloid, doesn't just create a setting; he crafts a hermetically sealed universe. The most immediately striking element is the deliberate, almost theatrical use of color, famously dictated by the costumes designed by the legendary Jean Paul Gaultier. Characters change outfits – and thus, their very essence seems to shift – as they move between the blue-hued car park, the infernal red of the main dining room, the sterile white of the lavatories, and the verdant green sanctuary of the kitchen. It's a visual language that’s both breathtakingly beautiful and deeply unsettling, trapping the characters (and us) within rigid, symbolic confines. This wasn't just set dressing; it was narrative architecture.

Monsters and Martyrs at the Table

At the heart of this claustrophobic world is Albert Spica, brought to life with terrifying, volcanic force by Michael Gambon. Spica isn't just a villain; he's a force of nature – crude, vulgar, relentlessly cruel, holding court over his terrified lackeys and his long-suffering wife, Georgina. Gambon’s performance is monumental, a masterclass in controlled chaos. He’s repulsive yet magnetic, his tirades on everything from digestion to his own perceived sophistication filling the air like toxic fumes. I remember watching him, utterly captivated by the sheer audacity of the portrayal – how could someone embody such ugliness so completely?

Counterbalancing this whirlwind of depravity is Helen Mirren as Georgina. Her performance is a study in quiet endurance and simmering rebellion. Trapped in a gilded cage, she finds solace and escape in a clandestine affair with Michael (a gentle, bookish Alan Howard), conducted under the nose of her oblivious husband, often with the tacit complicity of the compassionate French cook, Richard Borst (Richard Bohringer). Mirren conveys Georgina’s desperation, intelligence, and eventual transformation from victim to avenger with incredible subtlety. Her silence often speaks volumes, her gaze holding depths of pain and resolve that Spica, in his monstrous self-absorption, completely fails to see. It’s a performance that anchors the film’s emotional core amidst the stylized extremity. Bohringer, too, is wonderful as the stoic chef, a figure of artistry and morality caught in the crossfire of base desires.

Art, Appetite, and Atrocity

Greenaway isn't just telling a story of infidelity and revenge; he's orchestrating a complex allegory about consumption, decay, power, and the clash between brutish ignorance and refined sensibility. The exquisite food prepared by Richard becomes a symbol of art and creation, constantly juxtaposed against Spica's vile behavior and destructive impulses. The film’s structure, unfolding over consecutive nights, feels almost ritualistic, building towards an inevitable, shocking climax. Michael Nyman's powerful, repetitive score further enhances this sense of ritual and dread, its baroque flourishes clashing deliberately with the on-screen ugliness.

Let's talk trivia for a moment, because it illuminates the film's meticulous construction. Greenaway insisted on using real, often elaborate food prepared by chefs, adding another layer of sensory reality (and reportedly, logistical challenges under hot studio lights at Elstree Studios). The sheer visual overload – the painterly compositions reminiscent of Dutch masters, the extravagant costumes, the graphic depiction of both sex and violence – was entirely intentional. This wasn't accidental excess; it was a calculated aesthetic assault designed to provoke thought as much as revulsion. It’s fascinating to think that this challenging, uncompromising art film, made for a relatively modest budget (around $1.5 million), became such a talked-about phenomenon, eventually grossing over $7 million worldwide – a testament to its provocative power in an era often dominated by more conventional blockbusters.

The Lingering Taste

Spoiler Alert! for the next paragraph regarding the film's ending.

Of course, no discussion of The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover is complete without mentioning its infamous ending. The act of cannibalistic revenge Georgina orchestrates against Spica is one of the most audacious and unforgettable conclusions in modern cinema. It’s horrifying, yes, but also strangely cathartic and thematically perfect – the ultimate act of consumption turned back on the consumer. It’s the moment that cemented the film’s notorious reputation and ensured it would be fiercely debated for years to come. Was it gratuitous? Perhaps. But within the film's operatic, allegorical framework, it feels disturbingly earned.

End Spoiler

Watching it again now, decades after first encountering that distinctive VHS box, the film hasn't lost its power to shock, provoke, and mesmerize. It’s undeniably challenging, a film that demands patience and a strong stomach. It's not "entertainment" in the conventional sense. It's art designed to confront, to overwhelm the senses, and to linger uncomfortably in the mind. What does Spica’s boundless vulgarity say about unchecked power? How does Georgina’s transformation reflect the lengths one might go to for freedom? These questions feel just as relevant today.

Rating: 9/10

This near-perfect score reflects the film's audacious artistic vision, its stunning technical execution (cinematography, score, design), and the unforgettable, towering performances from Gambon and Mirren. It's a masterpiece of confrontational cinema, achieving exactly what it sets out to do with brutal elegance. The point deduction acknowledges its extreme nature, which undeniably makes it inaccessible or unpalatable for some viewers. It’s not a film you casually enjoy, but one you experience and grapple with.

The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover remains a potent reminder of a time when art-house cinema could still crash into the mainstream consciousness, forcing viewers to confront difficult truths wrapped in a darkly beautiful, unforgettable package. It's a dish that, once tasted, is impossible to forget.