The flickering static of a dying channel, the hum of the VCR late at night... sometimes the most unsettling images weren't the high-budget monsters, but the grainy ghosts captured on tape. Forget the gothic castles; the dread in Michael Almereyda's Nadja (1995) slithers through the cold, detached landscape of mid-90s New York City nightlife, a monochrome dream captured, in part, through the uncanny eye of a toy camera. Executive Produced by none other than David Lynch – a fact that feels less like trivia and more like a mission statement – this isn't your parents' Dracula. It's something altogether stranger, cooler, and infinitely more haunting.

Downtown After Dark

The premise feels almost like a deadpan joke filtered through existential ennui: Nadja (Elina Löwensohn), daughter of the recently deceased Count Dracula, wanders the bars and apartments of lower Manhattan, grappling with ennui, desire, and a deeply dysfunctional family dynamic involving her estranged twin brother, Edgar (Jared Harris). Pursued by a weary, almost bemused Van Helsing (Peter Fonda, miles away from Easy Rider but carrying a similar world-weariness) and his nephew Jim (Martin Donovan, a Hal Hartley regular perfectly cast as the bewildered everyman caught in the crossfire), Nadja's attempts to break free from her lineage only draw others deeper into her nocturnal world. The plot meanders, drifts like smoke in a dimly lit bar, less concerned with traditional scares and more with cultivating a pervasive sense of displacement and longing. Remember finding those oddities on the video store shelf, the ones with the intriguing covers that promised something different? Nadja felt exactly like that kind of discovery.

Shadows Through a Plastic Lens

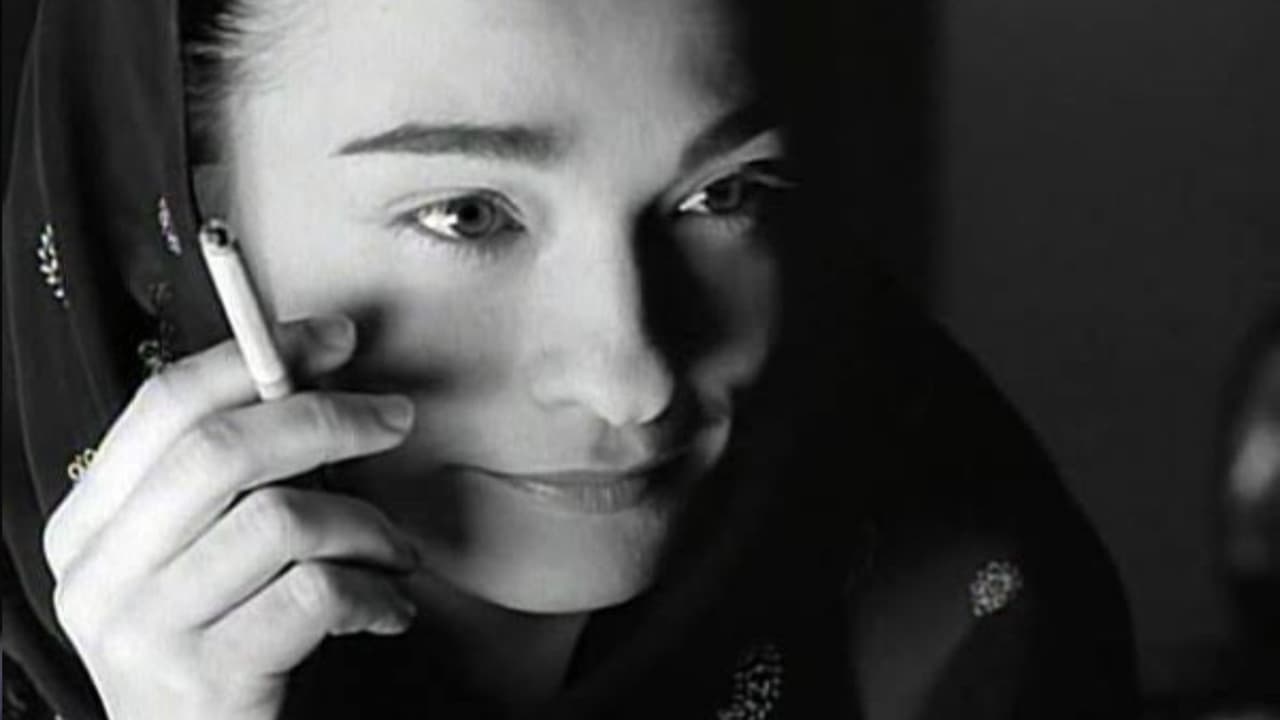

What immediately sets Nadja apart is its striking visual language. Shot primarily in stark black and white by cinematographer Jim Denault, the film evokes a timeless quality, grounding its supernatural elements in a recognizable urban reality. But it's Almereyda's audacious use of the Fisher-Price PXL-2000 camera for specific subjective sequences – Nadja's memories, her vampiric perceptions – that truly defines its aesthetic. This children's toy, recording blurry, low-resolution images onto audio cassettes, creates visuals that feel ethereal, fragmented, almost ghostly. It's a masterstroke born partly from necessity – the film was made on a shoestring budget, reportedly around $165,000 – but the effect is profound. It’s not just a gimmick; it viscerally conveys Nadja's alien perspective, a distorted reality shimmering just beneath the surface of the mundane. Did that grainy, almost abstract imagery feel more genuinely unsettling than any high-gloss effect back then?

Faces in the Monochrome Crowd

The performances are perfectly attuned to the film's unique wavelength. Elina Löwensohn, with her hypnotic gaze and unsettlingly calm demeanor, is Nadja. She embodies a creature of immense power and profound boredom, her vampirism less a curse and more a state of perpetual outsiderhood. Her delivery is flat, almost robotic at times, yet conveys currents of deep emotion beneath the placid surface. It’s a captivating, star-making turn. Opposite her, Peter Fonda brings a surprising pathos to Van Helsing. He's not the driven, righteous hunter of Stoker's novel, but a man seemingly resigned to the cyclical nature of his bizarre profession, armed with a water pistol filled with holy water and an air of existential fatigue. It’s said Fonda took the role partly due to his admiration for Almereyda's previous work and the script's unique tone – a choice that adds another layer to the film’s offbeat charm. Martin Donovan grounds the film as Jim, the relatable human anchor slowly pulled into this strange orbit, his confusion mirroring our own.

Indie Bloodlines and Lingering Echoes

Nadja arrived during a fascinating period for independent film and, specifically, for the vampire genre. Alongside films like Abel Ferrara's The Addiction (1995), it represented a move away from gothic romance and towards a more philosophical, urban, and art-house sensibility. These weren't just horror films; they were meditations on addiction, alienation, and the weight of history, dressed in leather jackets and navigating grimy city streets. The film’s soundtrack, featuring moody indie rock including a memorable cover of My Bloody Valentine's "Soon" by Pale Saints, further cemented its downtown cool credentials.

The Lynch connection feels palpable not in direct imitation, but in the shared appreciation for dream logic, unsettling atmosphere, and characters operating just outside societal norms. While Almereyda, who would later bring a similarly modern, media-saturated sensibility to Hamlet (2000), has his own distinct voice, the surreal touches and the focus on internal states over external action resonate with Lynch's work. The minimal budget ($165,000 wouldn't even cover catering on many Hollywood sets today - roughly $335k adjusted for inflation) forced a creative approach that ultimately became the film's strength, proving atmosphere doesn't require millions.

The Verdict

Nadja isn't a film that jumps out and shouts "Boo!" It creeps under your skin, leaving a lingering chill of existential dread and urban melancholy. Its pacing is deliberate, its mood pervasive, its visuals unforgettable. It's a film that rewards patience and immersion, a perfect late-night watch that feels like uncovering a secret transmission from a cooler, stranger dimension of the 90s. For those seeking conventional vampire thrills, look elsewhere. But for viewers who appreciate atmosphere, unique style, and a story that treats vampirism as a state of being rather than just a plot device, Nadja remains a potent and hypnotic experience. The PixelVision sequences alone make it a fascinating artifact of low-budget ingenuity.

Rating: 8/10

Nadja earns its score through its masterful creation of atmosphere on a minimal budget, its unique and influential visual style (particularly the PXL-2000 sequences), Löwensohn's captivating central performance, and its smart, melancholic take on vampire lore. It's a defining work of 90s indie cinema that feels just as coolly detached and strangely beautiful today. It perfectly captures that thrill of finding something truly original and unexpected waiting for you on the video store shelf.