There's a particular kind of quiet that settles in after watching Leaving Las Vegas. It’s not the comfortable silence of resolution, but the uneasy stillness that follows witnessing something profoundly uncomfortable, yet undeniably human. Released in 1995, this wasn't your typical Friday night rental fare, sandwiched between action blockbusters and rom-coms on the shelves of Blockbuster. Finding this tape felt like uncovering something raw and intensely personal, a feeling amplified by the grainy intimacy director Mike Figgis achieved, even on a fuzzy CRT screen.

A Descent into Neon Oblivion

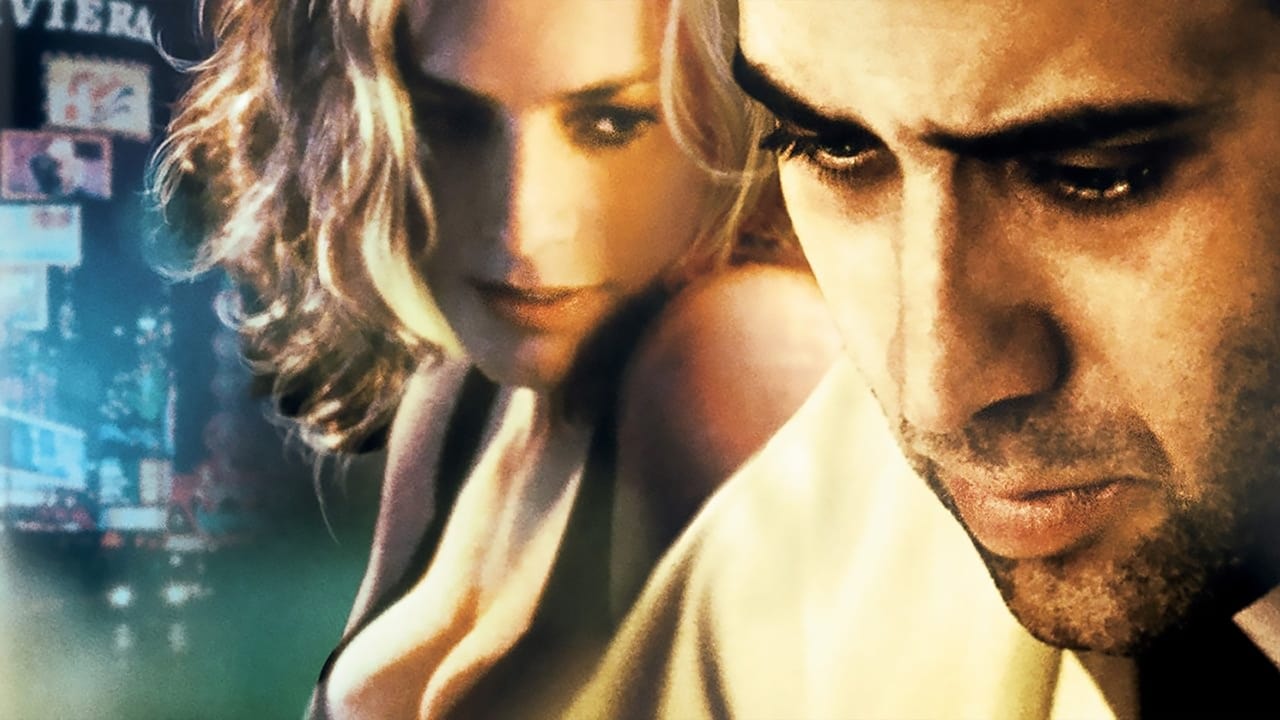

The premise is stark, almost brutally simple: Ben Sanderson (Nicolas Cage), a Hollywood screenwriter whose life has been consumed by alcoholism, cashes out everything he owns and drives to Las Vegas with the explicit intention of drinking himself to death. He doesn't want help, sympathy, or intervention. He wants oblivion, served neat in the city of dazzling excess and desperate loneliness. It’s there, amidst the casinos and dimly lit bars, that he encounters Sera (Elisabeth Shue), a prostitute navigating her own precarious existence under the control of an abusive pimp (a menacing, brief turn by Julian Sands). What unfolds is not a redemption story, nor a conventional romance, but a strange, deeply affecting pact of mutual acceptance.

Love in the Ruins

The heart of Leaving Las Vegas beats within the fragile, non-judgmental space Ben and Sera carve out for themselves. He accepts her profession without question; she accepts his relentless self-destruction without trying to change him. "I don't know if I came here to drink myself to death," Ben muses early on, a line delivered with a chilling mix of clarity and resignation. Their agreement is simple: she can never ask him to stop drinking, and he can never question her work. It's a relationship stripped bare of illusions, founded on a desperate need for connection, however fleeting or unconventional. Watching them find solace in each other's company, even as Ben physically disintegrates, forces us to confront uncomfortable questions about the nature of love, acceptance, and companionship at the absolute edge. Doesn't their bond, in its own harrowing way, reveal a fundamental human need to be seen and accepted, even in our darkest moments?

Performances Forged in Truth

This film rests almost entirely on the shoulders of its two leads, and their performances are nothing short of breathtaking. Nicolas Cage, in the role that rightfully earned him an Academy Award for Best Actor, is utterly consumed by Ben Sanderson. It’s a performance devoid of vanity, a harrowing portrayal of addiction that never feels like mere acting. Reportedly, Cage spent time binge drinking under medical supervision and studied alcoholic behavior intensely to capture the physical and psychological toll. The result is terrifyingly authentic – the slurred speech, the tremors, the brief flashes of the charming man lost beneath the disease. It’s a difficult watch, but undeniably powerful.

Equally transformative is Elisabeth Shue as Sera. Known more for lighter roles in films like Adventures in Babysitting (1987) and Cocktail (1988), Shue delivers a career-defining performance filled with vulnerability, resilience, and a quiet dignity. She navigates Sera’s complex world – the transactional nature of her work, the abuse she endures, her deep empathy for Ben – with incredible nuance. Her nomination for Best Actress was thoroughly deserved. There's a scene where Sera speaks directly to the camera, as if in therapy, that remains one of the most haunting and effective uses of breaking the fourth wall I can recall from that era.

Guerilla Filmmaking, Profound Impact

Knowing the context behind the production only deepens the film's impact. Director Mike Figgis (who also penned the screenplay based on John O'Brien's novel and composed the film's haunting jazz score) operated on a shoestring budget of around $3.6 million. Much of the film was shot quickly, guerilla-style, on Super 16mm film on the actual streets and casinos of Las Vegas, contributing immensely to its gritty, documentary-like feel. This wasn't the glamorous Vegas of postcards; it was the lonely, transient underbelly. The Super 16mm format, often seen as a budget compromise, here becomes an aesthetic choice, lending a grainy immediacy perfectly suited to the raw subject matter.

Tragically, author John O'Brien, whose semi-autobiographical novel inspired the film, took his own life shortly after the film rights were secured. This devastating real-life backdrop hangs heavy over the viewing experience, adding another layer of profound sadness. Figgis, to his immense credit, resisted studio pressure to tack on a more hopeful or redemptive ending, staying true to the brutal honesty of O'Brien's vision. It’s a testament to his artistic integrity that the film remains so unflinchingly bleak, yet finds shards of humanity within the darkness.

Last Call

Leaving Las Vegas is not an easy film. It doesn’t offer easy answers or Hollywood resolutions. It demands empathy for characters making choices many would find incomprehensible. It’s a film that stays with you, its melancholic mood lingering long after the credits roll – much like the faint buzz of neon reflecting off rain-slicked pavement. Back in the VHS days, finding a gem like this – so different from the usual escapism – felt significant. It was a reminder that sometimes, the most powerful stories are the ones that refuse to look away from the abyss.

Rating: 9/10 - The rating reflects the film's artistic integrity, the powerhouse performances from Cage and Shue, Figgis's evocative direction, and its unflinching, albeit harrowing, exploration of addiction and connection. It’s a near-perfect execution of a difficult vision, held back only by its inherently limited appeal due to the intensely bleak subject matter, which makes it a film admired more than perhaps "enjoyed" in the traditional sense.

It leaves you wondering: what endures more strongly – the devastation of self-destruction, or the defiant spark of acceptance found in the most unlikely of places?